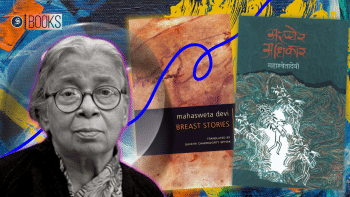

On motherhood and Mahasweta Devi’s ‘Breast-Giver’

For all the joys and agonies of motherhood, Jashoda did not flinch from suckling 50 children. It caught on to her though, the breast cancer, and perhaps more emphatically, the social alienation with which she is met—all this after being revered as the "Lionseated" incarnate, that is to say, Durga (the Mother Goddess in Hindu mythology) for suckling, as a wet-nurse, 30 children who were not her own. "When a mortal masquerades as God here below, she is forsaken by all and she must always die alone", so the story, "Stanadayini" ("Breast-Giver", 1980) by Mahasweta Devi goes. The short story is a critical imagination of motherhood—an exploration of the dynamics of oppression within which motherhood is so often embedded, particularly in the South Asian subcontinent.

Born in Dhaka, Devi (1926-2016) was a leading contemporary writer in Bangla, known as much for her political activism and grassroots work among marginalised communities of Bengal and Bihar. As for her fiction—also tinged with similar socio-political critique, and garbed in her distinctly direct yet subtle voice—roars themes of struggle and resistance in a way that somehow never feels ideologically heavy-handed.

"Breast-Giver" narrates the struggles of a "professional mother," Jashoda, a Brahmin woman driven to make ends meet by serving as a wet-nurse for the wealthy Haldar-household after an accident leaves her husband crippled. The men of the household, as well as the Mistress who runs it, acquiesce to Jashoda's role so that their own women could "keep their bodies" while breeding yearly as Jashoda bears the brunt of suckling their children. As a result, "Jashoda doesn't remember at all when there was no child in her womb." She feels empty "without a child at the breast. Motherhood is a great addiction." While Margaret Atwood's exemplary novel of Western feminism, The Handmaid's Tale (1985), imagines the woman's body being reduced to a breeding-vessel as a dystopia, "Breast-Giver" portrays how that is more of a reality than dystopia for many women in South Asia.

Jashoda's extraordinary "mammal projections" and "capacious breasts" soon become objects of envy for the Haldar-household and bread-winners for her own. The part of her body, symbolically heavy with connotations of womanhood is never sexualised, rather, constantly doused in the nectar of motherhood. This, however, is no bittersweet, humane form of motherhood—but motherhood stripped to its most primitive, (concurrently glorified) biological form, as exemplified by terms such as "mammal projections" and analogies likening Jashoda to the divine "Cow of Fulfillment" of the Hindu legends. As translator Gayatri Spivak has pointed out with regard to the significance of the story's title, the author "deliberately foregrounds the centrality of the female body in Jashoda's transactions with her clients—she is not just a 'wet-nurse,' a provider of milk, but a 'breast-giver.'" This distinction is amplified by the grim irony that ensues—she has literally given away her breasts when her body rots and putrefies at the clasp of breast cancer. Traditional female values such as unreasoning devotion and selflessness, all embodied by Jashoda, are thus undermined as "the self-destructive task of being mother of the world" unfolds in the course of the narrative.

In her delusions and death-throes, Jashoda mistakes everyone for her children: "The doctor who sees her everyday...the untouchable who will put her in the furnace, are all her milk-sons." This again merges with divine icons of motherhood such as mother of the universe, Shakti. Jashoda herself is named for Yashoda, the mother of the beloved cowherd-child-god Krishna. These mythic allusions interweaved within the narrative, coupled with the deceptively realistic, unsentimental, matter-of-fact tone in which the tale is told, make for an enthralling concoction. At the same time, the author's scathing satire makes you laugh at the follies of characters who are representatives of a society that we are all too familiar with. Devi's critique is sharp against not only the colluding forces of patriarchy and capitalism in the exploitation of the disadvantaged but also other issues entrenched in Indian society such as caste-based discrimination, provincialism, the remnants of British colonialism, and so on.

Reading "Breast-Giver," I couldn't help but think of the cultural significance of the word "ma" in our own society today; it is lead-heavy with meaning and so frequently invoked—from commonplace addresses of tender respect for women (think of the doctor who addresses you as ma) to motherly depictions of the landscape of Bengal in artworks, songs, and films. Moreover, "Breast-Giver" not only underlines the socio-religious significance of motherhood in Indian society, but also the peculiar psycho-social significance—with which we may be more familiar. For example, consider the lines: "Her [Jashoda's] mother-love wells up for Kangali as much as for her children. She wants to become the earth and feed her crippled husband and helpless children…Sages did not write of this motherly feeling of Jashoda's for her husband…Such is the power of the Indian soil that all women turn into mothers here and all men remain immersed in the spirit of holy childhood."

The narrator then highlights the hypocrisy of educated, liberal-minded men who deny this phenomenon "to the effect of the 'eternal she'—'Simone de Beauvoir,' et cetera": "It is notable that the educated Babus desire all this [only] from women outside the home" but, inside the home, "they want the Divine Mother in the words and conduct of the revolutionary ladies. The process is most complicated." The narrator seals this critique with tongue-in-cheek that made me giggle: "Because he understood this ["process"] the heroines of Saratchandra always fed the hero an extra mouthful of rice." Saratchandra precisely catered to that elite strata of liberal male readership. Moreover, the classic trope of the wife feeding the husband rice, as a depiction of the epitome of romance, similarly runs rampant in Bengali and Bollywood films. This odd mouth-feeding fetish appears embedded within the collective psyche of our society, much like the "belly-centered consciousness" of Jashoda's husband.

"Jashoda's death was also the death of God," the story ends. I read this line as a reference to the passing of the old order and the arrival of the new, with the new Haldar daughters and granddaughters refusing to have children. Notably, Jashoda becomes all the more alienated after these in-laws start moving out and the traditional family thus breaks apart.

At the same time, "Breast-Giver" seems a prefiguration of and an affirmative nod to American intersectional feminist Audre Lorde's famous statements: "the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women [like Jashoda] who still define the master's house as their only source of support." Gender norms are upturned in the story: the husband cooks and the wife works, yet the status of wage-earner does not liberate Jashoda because she relies on the "master's" idea of motherhood for support. Finally, seeing her decaying body, her own people stop visiting her at the hospital. To them, "Mother meant hair in a huge topknot, blindingly white clothes, a strong personality. The person lying in the hospital is someone else, not Mother." What does mother mean to us and how rigid or fluid is our idea of motherhood?

Syeda Fatema Rahman is a writer from Dhaka, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments