Prof. Abdur Razzaq on India's partition and independence

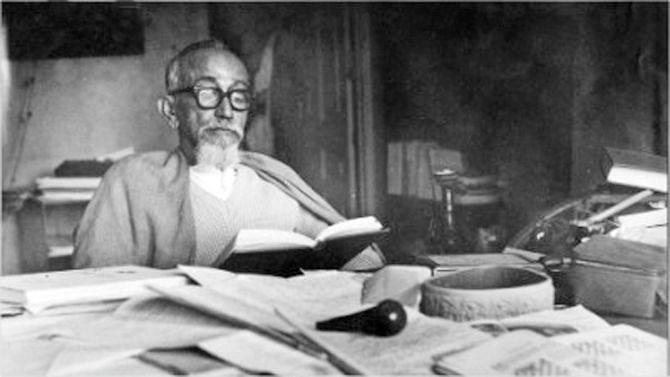

2014 is the birth centenary of renowned intellectual National Professor Abdur Razzaq. We are publishing this article to commemorate the occasion

PROF. Abdur Razzaq (1914-1999) played an important, even leading, role in giving a new orientation to intellectual life in Dhaka since 1950s. In 1931 he was admitted to the undergraduate classes of Dhaka University and in 1936 his alma mater accorded him the position of assistant lecturer. In 1945, after some ten years in Dhaka, he went on to London in pursuit of a post-graduate degree. A little over six years in the University of London did not prove enough for him to attain his goals. Abdur Razzaq returned home without a degree, although he did complete a Ph.D. dissertation under the noted pundit H.J. Laski. The topic of his thesis was 'Political Parties in India,' and it was date-marked May, 1950 for submission. Abdur Razzaq, in the event, did not pursue the matter further.

Although Abdur Razzaq's thesis has not been published in full, I have been one of the few persons privileged to read it. A photocopy of previous photocopies that I now have access to is, to tell the truth, partly unreadable but the work itself is undeniably important and, despite ravages of time, deserves publication. Soon after his return from England, Abdur Razzaq was lured by the call of questions of unequal development and disparity in East Bengal and of course military rule in Pakistan. They perhaps explain, but not fully, throwing cold water on burning questions of 1947.

Abdur Razzaq's thesis has two principal strands, namely that the greater credit for partition in 1947 goes to Indian National Congress, the premier political party in place, and that it was so because of the fact that the educated middle class had always been ruling the roost in Congress politics itself. Abdur Razzaq elucidates why in 1947, besides independence, partition of India also became a fait accompli, a God's act in a manner of speaking. Abdur Razzaq's first argument, a wide belief otherwise notwithstanding, is that India was bifurcated in 1947 at the instance primarily of the Indian National Congress. “The Congress was working hard,” in our author's indelible idiom, “for the division of India, notwithstanding the numerous protestations to the contrary.”

“In the following pages,” writes Abdur Razzaq, “an attempt has been made to explain the division of India by reference to the 'climate of thought' of the educated Indian whose task it was to initiate the political movements in India.” “The 'climate of thought' of the educated Indian,” Razzaq added, “has been sought not so much in the writings in the newspaper press as in the permanent contribution of the two vernacular literatures, Bengali and Urdu, of India.” “In the permanent contributions to these literatures, is enshrined the results of the 'searchings of heart' begun in the early years of the Nineteenth Century.”

The “uncompromising rivalry between the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League, resulting in the division of India,” according to Abdur Razzaq, however, it was only a “consequence in the political field” of what has frequently been known as 'national renaissance' (or nationalism) in the field of ideology. “The Congress doubtless had a political objective,” as an official historian of the Indian National Congress puts it, “but it was also the organ and exponent of national renaissance.” Abdur Razzaq aptly cites a rather long extract from the historian Sitaramaya's work: “All these movements (referring to schools of Hindu religious thought) were really so many threads in the strand of Indian Nationalism and the Nation's duty was to evolve a synthesis so as to be able to dispel prejudice and superstition, to renovate and purify the old faith, the Vedantic idealism and reconcile it with the Nationalism of the new age. The Indian National Congress was to fulfil this great Mission.”

Here comes the next strand, the question of a rising middle class or bourgeoisie if you will, in the argument. “The political movements in India led by the Congress, or by other political organisations, derived their character and characteristics from the fact that such movements were entirely led by the educated middle class,” writes Abdur Razzaq. “Others participated, at least in the later stages,” he admits, “but the leadership was exclusive.” The educated middle class imprinted its principal characteristics on the character of the political movements, as Abdur Razzaq insists, even if culmination of the political processes was not a function of political movements alone.

Abdur Razzaq, quite understandably, focuses on the last quarter century of colonial rule, (i.e. after the passing of the Government of India Act, 1919) when political power had to be devolved per force in Indian hands, albeit stage by stage. In the early days of political agitation, power being exercised by a foreign bureaucracy, politics had to be but tinged with colours of Indian nationalism, whereas in the last days of British India power was being handed out to Indian hands piece by piece. Both stages left their indelible marks on the political field. It is in this period that contestation became confrontation.

Political independence of India, insists Abdur Razzaq, was by no means the sole product of the political movement in the country. “If the end of the political process was in the independence of India, that end was being hastened, to a great extent, by the working of the machinery of government, as well as by the forces the economic evolution was generating.” There was a degree of interdependence between the colonial government and the educated middle class. “The strength of the political movements,” Abdur Razzaq observes, “was in the fact that the educated middle class which led them was also the principal class through which the government carried on its day to day existence. There was no question of strangling that class without strangling the government itself.” The growth of legislatures in late colonial India thus closely reflected the composition of the machinery of the government.

Abdur Razzaq locates two threads, other than political movements, in India's march toward independence. “The consummation of the political process resulted first from the transformation of the apparatus, civil and military, in composition as well as in character.” A second thread is to be found nowhere other than in the dwindling interest of British financiers in India. He cites data showing an actual shrinkage of export of capital from Britain between 1913 and 1927. More notably, India's share as a percent of British investment in the Empire was also dwindling in the 1920s. During the pre-war period America was the principal area of investment claiming fifty three percent. India was getting nine percent. India's share was not large. “But between 1924 and 1927 a revolutionary change had taken place. In the second period India was sharing with Trinidad, Jamaica and the Irish Free State the total of one fourth of one percent. The flow of capital from England to India, never very large, had practically dried up.” “When capital used to flow to India,” moreover, “it did not seek industrial investment to any large extent. It came in the form of government loans.”

But later, when the colonial government was beginning to float loans in the local market, it did so without having recourse to external borrowing. To cite only one instance, Sir Basil Blackett, finance member of the Government of India at the time, makes a remarkable declaration in 1926. The Government, he declares, would require to raise a loan of £220 million, “but there was no likelihood of our having to resort to external borrowing during 1926-27, this being the third year in succession in which external loans will have been avoided. More than the whole of new capital programme amounting to over £350 million will be financed without recourse to foreign borrowing.”

“Sir Basil Blackett was declaring that,” remarks Abdur Razzaq, “new masters had arrived on the Indian scene.” Political structures reflecting the importance they had attained by then had not yet surfaced. Political parties into which they could have federated, according to Abdur Razzaq, were yet of the future. Paths that political parties in independent India and Pakistan would follow in the near future were something altogether novel.

Abdur Razzaq's arguments, by now also taken up by many others, have grown neither familiar nor quaint. Their relevance can be overestimated only at our peril. We, however, are running out of space here. The sustainability or otherwise of his arguments must await another occasion, especially the eventual publication of whatever can be rescued from the available material in our midst.

The writer is Professor, General Education Department, University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments