Bangladesh’s forgotten villain

Bangladesh has a curious love affair with villains—particularly those neatly wrapped up in legal jargon. Mention the Digital Security Act (DSA) or the Information and Communication Technology Act (ICT) at your next coffee catch-up, and you'll witness rants more passionate than your melodramatic cousin's Facebook poetry. But casually bring up the Special Powers Act (SPA), 1974, and watch the room go eerily quiet, as though you've referenced an awkward family scandal nobody wishes to recall. It's our quietly menacing dinosaur, a relic still lurking unnoticed in our legal attic—outdated, oppressive, and embarrassingly overdue for retirement.

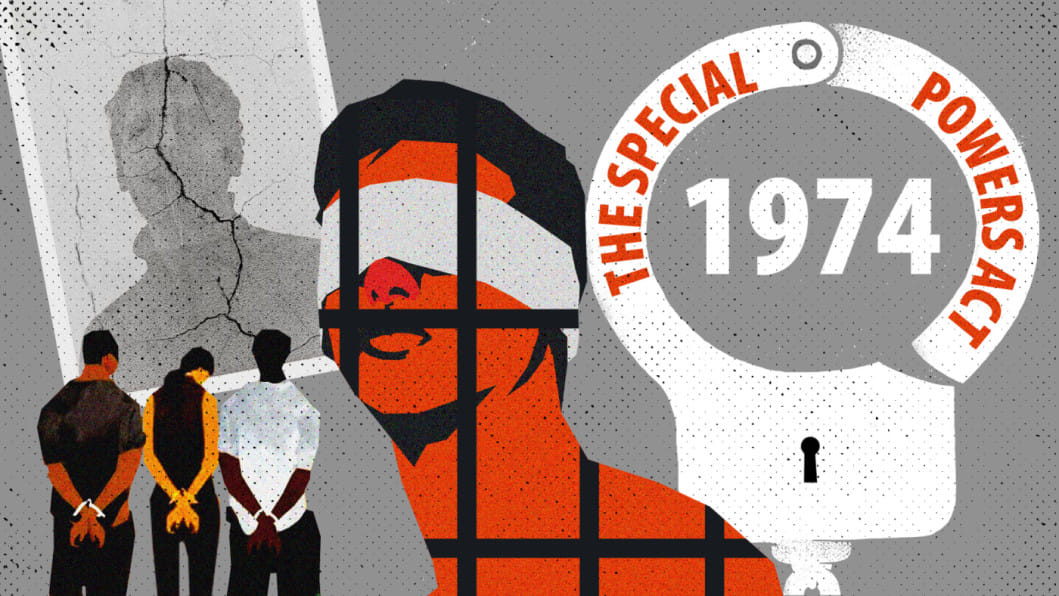

The Special Powers Act isn't merely another oppressive law—it's the patriarch of Bangladesh's infamous "black laws," a term lovingly reserved for legislation designed primarily to silence anyone who dares to disagree with those in power. Born in the chaotic year of 1974—presumably when human rights were as optional as side dishes at a wedding—it hands the government a chilling ability to detain individuals without bothering with formal charges or pesky courtroom procedures. Initially, the detention is for six months, but here's the diabolical detail: these six-month periods can be renewed indefinitely. Think of it as Bangladesh's own twisted version of Hotel California—you can attempt to check out anytime, but good luck actually leaving.

What's especially alarming is how comfortably the SPA tramples over constitutional protections that are supposed to be sacred. According to Article 33(1) of the Bangladesh Constitution, any arrested individual must be promptly informed of their alleged crime and must have access to legal counsel. Additionally, Article 32 explicitly guarantees protection against arbitrary deprivation of life and liberty. Yet under the SPA, detainees frequently find themselves in a Kafkaesque nightmare—imprisoned indefinitely without knowing their supposed wrongdoing, without lawyers, and without recourse. It casually shreds the principle of habeas corpus, a cornerstone of any legitimate democracy, as if tossing away an unwanted food delivery flyer.

This form of preventive detention cheerfully ignores fundamental due process, casually discarding the rights to a fair trial and presumption of innocence, concepts our constitution claims to uphold. Terms like "prejudicial to national security" or "disturbing public order" are deliberately vague, conveniently allowing authorities to target virtually anyone—from outspoken journalists and opposition figures to students whose only crime is to exercise their democratic rights.

Ironically, while activists justifiably raise hell over digital censorship via the DSA, the SPA goes quietly unnoticed, merrily detaining people without causing hashtags, tweets, or even the mildest online outrage. Amnesty International and Human Rights Forum Bangladesh have previously pointed to thousands of SPA detentions, citing devastated families, disrupted careers, and traumatised communities. Yet somehow, the SPA remains invisible in everyday conversations—too old-fashioned, perhaps, to fit neatly into viral social media campaigns.

The political hypocrisy around this law is staggering. Every major party, when out of power, rails vehemently against the SPA, vowing passionately to erase it from the books the moment they assume power. Predictably, once seated comfortably in office, they conveniently discover its usefulness. It becomes their favourite broom, sweeping away political irritations quietly and efficiently. It's become a tragically predictable cycle—opposition outrage quickly fades into governmental complacency.

At present, Bangladesh finds itself led by an interim government promising significant institutional reform. Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus, now overseeing the transition, speaks eloquently about restoring democratic norms and constitutional rights. These reforms have inspired considerable hope. Yet, curiously absent from the discourse is any meaningful effort to address, amend, or—heaven forbid—repeal the SPA. It's as if everyone is busily rearranging furniture in a sinking house while ignoring the colossal, dinosaur-shaped hole in the ceiling.

Over decades, civil society leaders, legal experts, and human rights advocates have tirelessly argued that the SPA's unchecked powers are fundamentally incompatible with democratic ideals. Young Bangladeshis, whose hashtags and social-media-driven activism have changed national conversations, are growing increasingly impatient with a law older than their parents, and twice as outdated. This dissatisfaction is real, even if it isn't trending on Instagram. The lack of information and conversation around this topic is equally concerning.

Despite its severity, the SPA has mostly escaped international scrutiny, mainly because it's quietly old-school compared to flashier digital laws. Even as Amnesty International reported worrying spikes in SPA detentions during the previous election unrest, global and local outrage barely surfaced. It seems detention doesn't count unless it comes with trending hashtags and retweets.

Behind the legal jargon, families bear the genuine cost of this act. Loved ones vanish into detention, leaving behind confused and traumatised relatives without answers, recourse, or support. Entire communities are held hostage by fear. Yet, because this abuse happens discreetly rather than dramatically, it fails to attract widespread empathy. Apparently, silent suffering doesn't make great headlines.

However, the interim government now has a historic opportunity—indeed, a moral obligation—to confront this embarrassing and dangerous law. A dedicated, independent commission must urgently review the SPA, offering meaningful, rights-respecting alternatives. Many democracies worldwide manage national security concerns without permanently sacrificing constitutional protections. Judicial oversight, transparency, and accountability are achievable goals; Bangladesh certainly doesn't lack the capability, merely the will.

Repealing or radically reforming the SPA wouldn't merely be symbolic—it would signify a profound and lasting shift in the state-citizen relationship. It would finally honour constitutional promises made under Articles 32 and 33(1), bringing Bangladesh closer to genuine democracy.

So, next time you sit with friends, passionately dissecting the latest digital outrage over overpriced cappuccinos, perhaps spare a thought (and a hashtag) for this quietly terrifying villain. The Special Powers Act has lurked in our shadows since 1974—far too long, and far too damaging, to continue going unnoticed.

It's high time Bangladesh finally confronted this sinister dinosaur. Let's consign it where it belongs: safely in history's junkyard, alongside outdated rotary phones, embarrassingly wide bell-bottom pants, and every other idea best left firmly in the past.

Barrister Noshin Nawal is an activist, feminist, and a columnist for The Daily Star. She can be reached at nawalnoshin1@gmail.com.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments