Raja Pratapaditya Charitra and the Birth of Bengali History Writing

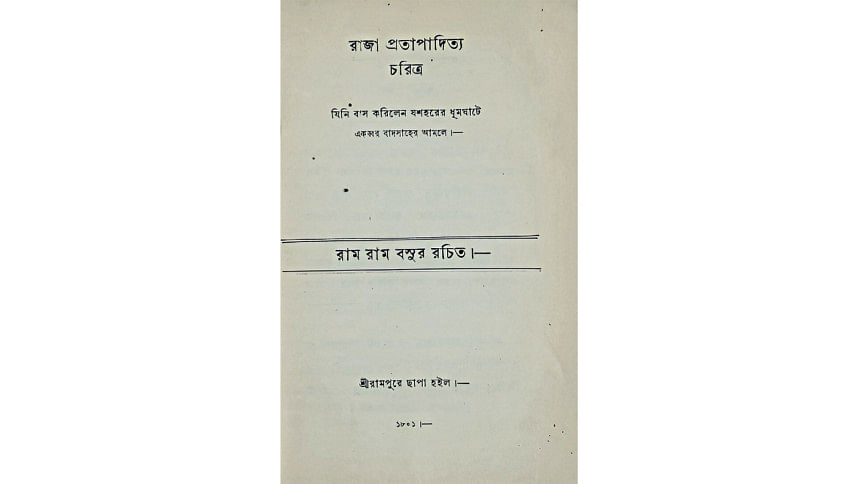

The writing of history in the Bengali language by a Bengali began around 225 years ago with the publication of Raja Pratapaditya Charitra in 1801. The book was printed by the Serampore Mission Press, under the commission of Fort William College, which had been established just a year earlier, in 1800, by Governor General Lord Wellesley. That same year, the founding of the Serampore Mission Press ushered in a new era of book printing in Bengal. Raja Pratapaditya Charitra was authored by Munshi Ramram Basu (1757–1813), a native scholar at Fort William College, and commissioned by William Carey (1761–1834), who headed the newly founded Bengali department. The book holds both historical importance and literary significance, as it was the first Bengali prose work written by a Bengali and the first Western-style historical narrative in Bengali.

Sajani Kanta Das mentioned that Ramram Basu wrote this book just two months after being assigned the task. What drove him was sheer courage, as he had no prior model of Bengali prose or historical writing in the language to guide him.

The book narrates the story of Raja Pratapaditya, a sixteenth-century ruler of Jessore who lived in the Mughal era. Nearly two centuries later, it was adopted as a textbook at Fort William College to help students—who were being trained for administrative roles under the British East India Company—learn the local history and vernacular of Bengal.

The Time of Ramram Basu

Who was Ramram Basu, the first Bengali historian of the colonial era, who introduced the practice of writing history in the Western manner—though he initially relied more on intuition? Despite being a relatively obscure figure during his lifetime, with little known about his family background, his work had a lasting impact: it helped shift historical writing in India from an intuitive to an institutionalized form. His greatest strength was his command over languages. Missionaries noted that he spoke English fluently, had a strong grasp of Persian, and wrote Bengali with remarkable finesse. He was not only an insightful prose writer but, before that, he excelled in satire, with his poetry marked by sharp intellectual intensity.

Born in 1757 at Chunchura, in the Hooghly district, Ramram Basu learned Bangla and Persian to make a living. Later, when he came into contact with several Englishmen, for whom he worked as a Persian munshi and scribe, he also learned spoken English. In 1787, he was appointed as a Bengali teacher to the missionary John Thomas. Ramram accompanied Thomas to Malda, where he began teaching him Bengali. At that time, Thomas believed that many native people would eventually be converted to Christianity.

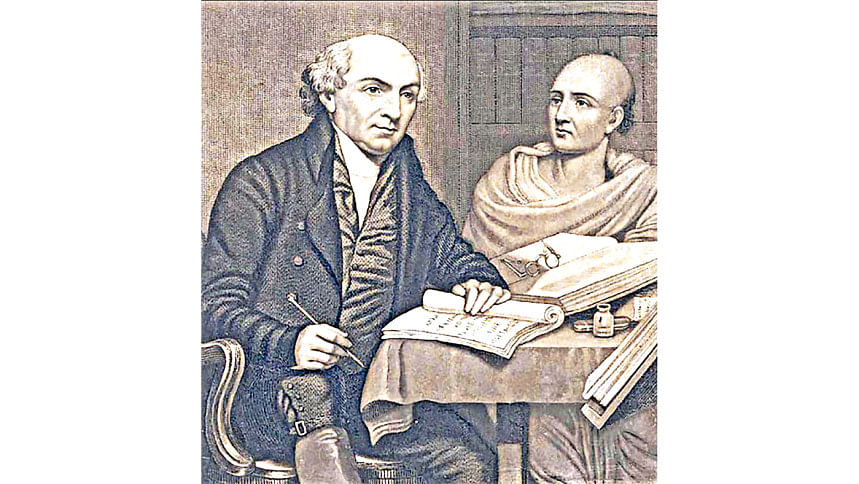

In 1793, William Carey—the renowned Baptist missionary and orientalist scholar, who had once been a shoemaker—arrived in Kolkata upon learning about the 'heathens' he sought to 'emancipate' from 'eternal fire.' He was accompanied by his family and another Baptist missionary named John Thomas. Almost immediately, Carey began learning Bangla and engaged Ramram Basu as his teacher with a salary of twenty rupees. With Basu's help, Carey later began translating the Bible into Bangla.

Ramram Basu's devotion and knowledge of Christianity, particularly his devotional poetry on Jesus, strengthened Thomas's firm belief that the mission was on the right path. At Carey's request, Ramram Basu wrote in praise of Christianity and against Hindu idolatry, leading both Carey and Thomas to believe that he would eventually embrace Christianity. However, this did not happen.

In 1796, an incident occurred in which Ramram had secretly become infatuated with a young widow, and when her child was found dead, Carey regarded it as a serious lapse in Ramram's moral integrity.

He was not heard from for several years after that. In 1800, Carey came to Serampore and met many people, including Ramram Basu. He was reappointed, as Carey recognized that preaching was not possible without the help of such a talented person as Ramram. Later, Carey was appointed as the principal of the Bengali department at Fort William College, where Ramram Basu was employed under him with a salary of 40 rupees.

For his work on Pratapaditya Charitra, he received 300 Taka from Fort William College. Before Pratapaditya Charitra, two of Ramram Basu's books, written in a poetic style, were published from Serampore in 1800 and 1801. Additionally, he assisted William Carey in refining the Bengali translation of the Bible. Ramram Basu passed away in 1813.

The reception of Raja Pratapaditya Charitra by later formal historians has been intriguing—not only for its pioneering role in historical writing but also for its own historical merits.

There is an assumption that Ramram Basu was familiar with Rammohan Roy, the pioneer of the Bengali Renaissance, as Basu was inspired by Roy's anti-idolatry writings. It is also believed that Ramram Basu sought help in finalizing the manuscript of Pratapaditya Charitra from Roy. However, both Brajendranath Bandyopadhyay and Sajani Kanta Das refuted this claim, pointing out that Roy's Bengali prose works only began to be published after 1815. Notably, his first book, written in Persian, was published in 1803–4.

Stories of Raja Pratapaditya Charitra

Pratapaditya was one of the foremost landowners among the 12 famous landowners known as the Bara Bhuyans of Bengal, with Isa Khan being the most prominent among them. Ramram Basu narrated the history of Pratapaditya chronologically, relying on what he found in previous Persian texts and oral traditions from his family about the 16th-century king, as they belonged to the same caste. In doing so, he blended both fact and fiction, with his writing reflecting both objective and subjective positions.

The story starts with Ramchandra, a Kayastha from East Bengal, who left his ancestral home in search of fortune and settled in Saptagram, where he found work in the tax collector's office. He had three sons—Bhabananda, Gunananda, and Sibananda—of whom Sibananda was the most promising.

For a time, the family lived together harmoniously. However, when Sibananda had a disagreement with a senior officer, they were compelled to relocate to Gaur. There, they were warmly received by King Solaiman, who granted them permission to settle.

Among the brothers, Sibananda, being the most astute, distinguished himself and gained special favor from the king. His two nephews formed a close friendship with Bajid and Daud, the nephews of Solaiman. Daud, in turn, promised to make them his ministers if he ascended the throne. Following his father's death, Bajid became king but was soon assassinated by Solaiman's son-in-law. However, the assassin was later slain by a loyal friend of Daud, who then ascended the throne.

This Daud was none other than the famous Daud Khan Karrani, the last independent Sultan of Bengal. Keeping his promise, he conferred the titles of Maharaja Vikramaditya and Raja Basanta Ray upon Srihari and Janakiballabha, the nephews of Sibananda.

However, Daud soon grew ambitious and refused to pay tribute to the Mughal emperor Akbar. Realizing that the emperor would take punitive action against Daud, the brothers wisely decided that remaining in Gaur would be too dangerous. They, therefore, built a permanent residence in what was then the remote maritime wilderness of Jessore and developed it around 1573.

In response to Daud's defiance, Akbar dispatched his general, Todar Mal, to subdue him. Terrified, Daud attempted to flee but was eventually captured and executed in 1576. Following his death, the Mughal general entrusted Srihari and Janakiballabha with governing the region.

Anticipating an invasion, Daud had previously sent his wealth and a significant stockpile of food to Jessore. As a result, after his execution, the two brothers became extremely wealthy and powerful. They were crowned with great pomp and splendor, inviting all their relatives, granting them land, and settling them in the area—thus marking the origin of the Bangiya Kayastha Samaj of eastern Bengal.

Srihari had a son named Pratapaditya, who, from an early age, displayed traits of cruelty and an insatiable thirst for power. To keep him at a distance and instill discipline, Srihari sent him to Delhi to be trained in state affairs.

In Delhi, Pratapaditya impressed Emperor Akbar with his talent for extempore poetry. However, he also schemed against his father, distorting facts to such an extent that the emperor ultimately granted him the authority to govern his father's domain.

Despite this betrayal, Srihari and his brother welcomed Pratapaditya back without outward resentment, seemingly untroubled by the humiliation he had caused them in the emperor's eyes.

A few months later, Pratapaditya relocated his capital to Dhumghat, transforming it into a grand city with magnificent mansions, a massive fort, and bustling marketplaces. In 1604, he ceased sending taxes to Delhi and became virtually independent. He significantly strengthened his naval power and was regarded as the last king of Sagur Island, even minting coins in his name.

Though Pratapaditya possessed admirable qualities, his flaws were equally pronounced. He was known for his generosity, but he was also ambitious, ruthless, arrogant, and intolerant. He built a formidable army and refused to pay tribute to the Mughal emperor. Driven by his thirst for power, he conspired against his own relatives and sought to suppress the kings who ruled estates in the province.

News of his treachery reached Delhi, enraging Emperor Jahangir. After a prolonged and sporadic series of battles, Pratapaditya ultimately surrendered. He died in Banaras while being taken to Delhi in 1606.

Following his downfall, the emperor appointed Raghab Ray, the eldest son of Basanta Ray, as the new ruler. However, when Raghab Ray returned to Jessore from Delhi, he found the once-glorious city devastated and desolate and maintained the Jessore Samaj.

Significantly, Ramram Basu's account of the death of Pratapaditya greatly varies from the depiction by the poet Bharatchandra Ray (1712–1760) in his Annadamangal, who was a closer contemporary of Pratapaditya. Although Basu did not specify the exact time and date of the events, later editors painstakingly added approximate dates based on the details he narrated in his book.

Reception as a Literary Text

Ghulam Murshid noted that while Ramram Basu's contemporaries in Bengali literature were primarily Sanskrit scholars who wrote in a Sanskritized style, Ramram's prose reflected his inclination toward Persian. The early reception of Raja Pratapaditya Charitra, however, was mixed, with many initial reactions being particularly negative. For instance, a review in the Calcutta Review (1854) criticized its style, describing it as a "kind of mosaic, half Persian, half Bengali." Similarly, Ramgati Nyayaratna, who wrote the first known history of Bengali literature, condemned Ramram Basu's indiscriminate use of Persian and Arabic words.

Shishir Kumar Das refuted these criticisms by providing a quantitative analysis of Pratapaditya Charitra. He calculated that the total number of Persian and Arabic words was 218, appearing 511 times within a text of approximately 14,976 words. The percentage of Persian words was only 3.4%, contradicting claims that Pratapaditya Charitra was heavily Persianized or linguistically unbalanced, as alleged in the Calcutta Review.

There is a common assumption that Fort William College's endeavor in the Bengali language aimed to sanitize it by removing Arabic and Persian influences, relying solely on Sanskrit under the guidance of its missionaries and pundits. However, Raja Pratapaditya Charitra contradicts this claim, as it contains numerous Arabic and Persian words. These words were likely colloquial at the time or commonly used in bureaucratic and administrative contexts. Ramram Basu incorporated these elements naturally, as Persian remained the official state language of India until 1835. That year, the English Education Act, introduced by Governor-General Lord William Bentinck, replaced Persian with English. Additionally, Fort William College also lost its significance when Haileybury College in England was established in 1806 for the newly recruited cadets of the Company.

Sukumar Sen highlighted that the emergence of prose style in Bengali literature marked the beginning of the modern age, as premodern Bengali literature was predominantly in poetic forms. He also stated that the early 19th century was a period when literary works were primarily instructive—designed to teach new ideas, informative in presenting new forms of thought, or discursive in justifying or rejecting different creeds. This transformation was significantly influenced by Christian missionaries and professors at Fort William College. Pratapaditya Charitra embodies both instructive and informative genres in this regard.

Moreover, the character of Pratapaditya gained significant importance, and numerous biographies and works of fiction were written about him. He became a figure of both admiration and controversy in nineteenth-century Bengal, particularly as the nationalist movement gained momentum. As a result, Clinton B. Seely characterizes Raja Pratapaditya as a "problematic hero."

The Legacy as a Historical Text

Both the sixteenth century, when Pratapaditya ruled, and the early nineteenth century, when the book was written, were pivotal periods for Bengal and India, marked by significant societal and political transitions. Moreover, the book played a pioneering role in the writing of history in Bengali, laying the foundation for future historical literature in the language.

Although Ramram Basu didn't explicitly mention that he was writing history in this book, he stated that he undertook the task due to the lack of a detailed account of the rise and fall of any kings in the region. Significantly, his employer, Carey, was quick to identify Basu's work as "history," as he wrote, "I got Ram Boshu [Ramram Basu] to compose a history of one of their kings."

Ramram Basu did not attempt to write a comprehensive history of India or Bengal in a chronological manner, as Mritunjay Bidyalankar did in Rajaboli (1807), a Bengali work from the same Fort William enterprise. Instead, he focused on the local but significant figure of King Pratapaditya, with whom he felt an affinity due to their shared Kayastha lineage within Bengal's Hindu caste system. Later, historical writings on both local rulers, such as Krishna Chandra, the king of Krishnanagar, and detailed chronological narratives of regions gained popularity, emerging from both the college's initiatives and private efforts, which would become increasingly significant over time.

The reception of Pratapaditya Charitra by later formal historians has been intriguing—not only for its pioneering role in historical writing but also for its own historical merits. For instance, Jadunath Sarkar found the first part of Pratapaditya Charitra to be entirely historical, while other historians regard the book as a valuable sourcebook, as Ramram Basu blended both fact and fiction in his narrative. While Ranajit Guha, one of India's foremost historians, noted that Ramram Basu's narrative occasionally lapses into myth and fantasy, many historians agree that this flaw—almost unavoidable under the circumstances—has done little to undermine the overall authenticity of the work as an exercise in modern, rationalist historiography.

The Indian subcontinent was regarded as a historyless and stateless society, where the absence of prose writing in vernacular languages was seen as a sign of underdevelopment. From this perspective, Raja Pratapaditya Charitra stands as a monumental endeavor, both in terms of writing history and fostering prose in the Bengali language. While it may have initially appeared as part of a colonial project, patronized by colonial institutions and figures, it soon evolved into a distinctly native enterprise. What began as a form of local history writing ultimately became an integral part of global history.

Priyam Pritim Paul is a researcher and journalist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments