Origins of Phrases

Henry Kissinger, misunderstood for his ‘basket case comment’.

Henry Kissinger, misunderstood for his ‘basket case comment’.

Henry Kissinger would certainly find a place near the top of any list of the most cerebral Secretaries of State in American history. He is very much a global celebrity even today, thirty six years after he held high office. Bangladeshis, though, remember him mostly for reasons that are not quite uplifting. In Bangladesh, it is widely believed that soon after liberation, he described the new country as a “basket case”. Outside Bangladesh also there are many who associate Kissinger with the “basket case” comment. Last year, in an article entitled Bangladesh: Out of the Basket, the Economist noted that this was “Kissinger's dismissive term” for Bangladesh. The late author Christopher Hitchens, in his book The Trial of Henry Kissinger, attributed to him the characterisation of Bangladesh as an “international basket case”.

The phrase “basket case” came into use after World War I. It applied to a condition deemed completely hopeless or useless, such as a quadriplegic or a quadruple amputee who needed to be carried in a litter. When the Habsburg Empire was dismantled after the War, “little Austria seemed a basket case”, to at least one commentator.

In recent years more information has come to light on the “basket case” remark. Christopher Van Hollen served as US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Near East and South Asian Affairs during 1969-72. He passed away earlier this year. The Washington Post in his obituary recalled that in a 1990 oral history interview, he claimed that he was “probably the source for the oft-quoted remark that Bangladesh was an international basket case”. He is said to have made the quip at a White House meeting chaired by Kissinger. The phrase, Van Hollen said, had “hung around Bangladesh's neck ever since”.

Declassified US papers also throw light on the “basket case” comment. On 6 December 1971, a meeting of the Washington Special Action Group was held in the White House “to consider the Indo-Pakistan situation”. Hostilities had broken out between India and Pakistan, and the former had recognised Bangladesh. The meeting was chaired by National Security Adviser, Henry Kissinger, and was attended by among others Deputy Secretary of Defense, David Packard, Chief of Army Staff, General William Westmoreland, Director, CIA, Richard Helms, Under Secretary of State and former Ambassador to Japan, U Alexis Johnson, Deputy Administrator of US AID, Maurice Williams and Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, Christopher Van Hollen. Gen Westmoreland's assessment was that Pakistan could perhaps hold out for three weeks or so “in the East”. Discussions focused on “the massive problems facing Bangladesh as a nation”. In response to a query from Kissinger, Maurice Williams said that Bangladesh would not face famine conditions that year, but there could be a problem by the next spring. However, if 140 tons of food could be funneled through Chittagong each month the problem would not arise. He added that Bangladesh would “need all kinds of help in the future”. Johnson remarked that Bangladesh would be an “international basket case”. Kissinger observed: “it will not necessarily be our basket case”. Going by official records, the “basket case” comment was made by Johnson at a closed door meeting; Kissinger merely concurred in an off-hand sort of way. The object, one may assume, was not to denigrate, but to underscore the plethora and magnitude of problems that confronted Bangladesh at that time. Van Hollen would go on to serve as Ambassador to Sri Lanka, and Johnson would subsequently be named chief US delegate to the strategic arms negotiations with the USSR in Geneva.

The phrase “an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth” conveys a sense of equity and rough justice. In other words, the punishment must be commensurate with the offence or crime; the emphasis is on retribution and deterrence. This has for long guided, even driven, the administration of criminal justice in countries of the world. In modern times there is an added element, the rehabilitation of the offender, where appropriate. The phrase appears in two Books of the Old Testament. Deuteronomy (19:21), under the Law concerning Witnesses, says: “...but life shall go for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot”. And Exodus (21:24), under Laws concerning Acts of Violence: “eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot”. It is also cited in the New Testament, although its central message or purport is not endorsed, is in fact disavowed. The Gospel of Matthew (5:38), under Love for Enemies, says: “Ye have heard that it hath been said, an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth; but I say unto you, that ye resist not evil; but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also”. This is very like Mahatma Gandhi's philosophy of non-violence. Gandhi is said to have once observed that “an eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind”.

The phrase “eye for an eye”, or its message, in fact originated even prior in time to the Old Testament, in the Code of Hammurabi, the sixth king of the first Amorite dynasty of Babylon, who ruled more than seventeen centuries before Christ. His legal code, carved in a diorite column, covered an array of subjects. A passage on physical punishment reads: “If a man destroys the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye”.

In modern times, opinion is divided on the issue of capital punishment. A number of developed countries have abolished it, and many human rights organisations firmly believe that it constitutes a violation of the most basic of human rights. Even in countries that still have the death penalty, it is applied sparingly, unlike in times past. In 18th century British India, for example, Maharaja Nanda Kumar was hanged for forgery, and in the American Wild West of old, stealing horses was a capital offence.

In Bangladesh, a recent verdict of the International Crimes Tribunal precipitated a prompt, spontaneous and even strident public reaction. This does suggest that for particularly gruesome crimes and atrocities, the saying “an eye for an eye” still has a resonance for peoples.

Pakistan's last Governor General and first President, Iskander Mirza, was among the early Sandhurst-trained King's Commission Officers of the British Indian army. Subsequently he was seconded to the elite Indian Political Service. Another person appointed to the IPS at the same time as Mirza was KPS Menon, who had topped in the ICS batch of 1921. Menon would later become the first Foreign Secretary of independent India. Mirza was descended from the Moghul-appointed rulers of Bengal, and in the words of former British High Commissioner to Pakistan, Sir Morrice James (Pakistan Chronicle), “though not himself a Bengali, he was touched by Bengali refinement and sophistication”. As President, Mirza showed a fondness for the phrase, “my country right or wrong”. The phrase suggests an abiding and intense love of country. It was not coined by Mirza; he never sought to dispel the notion, though, that it was.

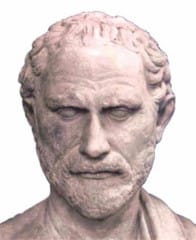

Demosthenes of Athens was a renowned orator and statesman of ancient times. He was stoutly opposed to the southward expansion plans of Macedon's Phillip II. In 338 BC, at the battle of Chaeronea between Athens and Macedon, he fought as a hoplite or citizen-soldier. Macedon was victorious, and Athens suffered heavy casualties. Demosthenes fled from the battlefield, and later delivered the funeral oration for those who had fallen. To taunts of cowardice—as he had fled from battle—Demosthenes retorted, “The man who runs away may fight again”. The modern day version of this is: “He who fights and runs away will live to fight another day”. A kindred dictum would be: “Discretion is the better part of valour”. At the end Demosthenes did not quite measure up to his own maxim. In 322 BC, he committed suicide to avoid capture by the then ruler of Macedon, Antipater.

St Ambrose, St Augustine, St Jerome and Gregory the Great are recognised as the original Doctors of the Western Church. They were men of “eminent learning” and “great sanctity”, who made significant contributions to theology and doctrine. On a visit to Milan in 387 AD, St Augustine was puzzled that the Church did not fast on Saturday, as did the Church of Rome. The Bishop of Milan, St Ambrose, explained this inconsistency to him: “When I am at Rome, I fast on a Saturday; when I am at Milan, I do not”. In the 18th century, English scholar, Robert Burton, in his book, The Anatomy of Melancholy, modified this comment to “When they are at Rome, they do there as they see done”. Over time this evolved into the familiar maxim, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do”.

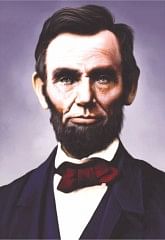

On 19 November 1863, Abraham Lincoln delivered what is possibly the most edifying and enduring speech in the English language, the Gettysburg address. The concluding words of the speech constitute a succinct and felicitous definition of democratic government, “government of the people, by the people and for the people”. It is a speech that very nearly was never made.

The battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania in July 1863 was a turning point in the American civil war. General Lee's push to the North was repulsed and ended. Some eight thousand soldiers of both sides lost their lives. Shortly afterwards the Committee for the consecration of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg, where those who had fallen in battle were buried, invited Edward Everett to deliver the oration at the dedication ceremony of the Cemetery. Everett was a person of great distinction and high achievement. He had served as Governor of Massachusetts, US Senator, Secretary of State, Envoy to Britain and President of Harvard. He had more than a month to prepare his address. The President, members of the cabinet, Senators and Representatives were invited to the ceremony. Most of them declined; somewhat surprisingly the President accepted. The Committee was faced with an awkward question; should the President be requested to speak at the ceremony? Everett was the most celebrated orator of the time. How would Lincoln—an autodidact with only a year's formal schooling in life—measure up against him? A fortnight before the event, Lincoln was belatedly invited to make “a few appropriate remarks”. Everett spoke for over two hours, and Lincoln, who spoke after him, for about two minutes. His speech was a masterpiece in miniature. Gettysburg today is remembered as much—possibly more—for his speech, as for the battle that was fought.

Even before Lincoln, others had defined democracy in terms that are very similar to the phrase used by him in Gettysburg. In 1850, Theodore Parker, reformer and abolitionist, had said in a speech, “Democracy is direct self-government, over all the people, by all the people, and for all the people”. Some years earlier, American statesman, Daniel Webster, speaking in the Senate had declared: “…people's government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people”. Centuries before Webster, John Wycliffe, philosopher, theologian and also dissident in the Catholic Church, in the preface to his translation of the Scriptures had written: “this Bible is for the government of the people, by the people, and for the people”. And in the 4th century BC, Cleon of Athens, in an address to the “men of Athens”, had spoken of a ruler “of the people, by the people, and for the people”. Cleon was a charismatic and populist leader; whether he coined the phrase himself or drew inspiration from an even earlier unknown source will never be known.

The power of words, when properly harnessed, can be extraordinary. It can transcend the barriers of time, nations, culture and even language.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments