The monsters we make

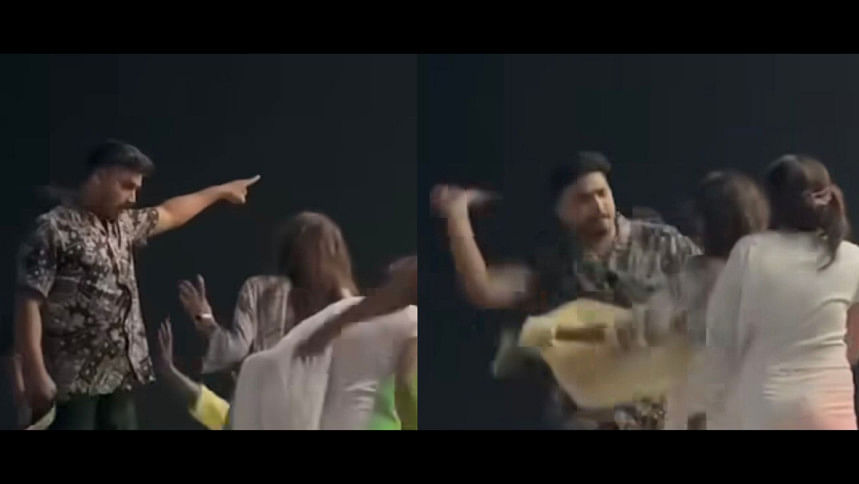

On 10 May, a man named Nehal Ahmed Jihad brutally assaulted two women with a belt in full public view at the Munshiganj river terminal. The crowd did not intervene, help the girls or stop him. Instead, they cheered, clapped, and filmed the incident. Some could even be heard screaming, "That's what they deserve!"

Disturbing? Extremely.

But what forced me to look deeper was Jihad's vile justification afterwards: "I did that to discipline them, as their elder brother."

It made me wonder. What kind of family did he grow up in? Does he truly believe that's what elder brothers are supposed to do? Do they beat their women like this?

Jihad's warped reasoning, cloaked in a twisted sense of familial duty, exposes how such poisonous beliefs are passed down through generations.

Abuse is normalised under the guise of protection, authority, and "discipline". And the silence -- or worse, the applause -- of the bystanders that day speaks volumes about the society we live in. When a woman is beaten in broad daylight and the reaction is applause, not outrage, what does that say about the moral fabric of our nation?

Such acts of violence are the inevitable outcome of a society poisoned by patriarchy, misogyny, and deep-rooted inequality.

Across South Asia, gender-based violence remains alarmingly prevalent. UN Women reports that the proportion of women in Asia and the Pacific who have experienced physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner is substantially higher than the global average. In Bangladesh alone, 47 percent of married girls aged 15–19 who have suffered violence, did so at the hands of their own husbands or partners. Let that sink in. Nearly half of our young girls -- barely out of childhood -- are being brutalised in the name of "discipline", or whatever it is, by the very men who claim to "protect them".

And what happens next? The children born into these households grow up watching this horror unfold every day. Violence becomes normalised. It becomes a part of their upbringing.

According to UNICEF South Asia, exposure to violence during childhood significantly increases the likelihood of violent behaviour in adulthood. In Afghanistan, 74 percent children aged 2–14 have experienced some form of violent discipline. But is Bangladesh very different?

The Harvard Centre on the Developing Child explains that early exposure to "toxic stress" can disrupt brain development, impairing a child's ability to regulate emotions or control impulses.

These children are far more likely to lash out, to grow up angry, broken, and yes, violent. And when those developmental wounds go untreated and are compounded by a society that teaches boys to be dominant and girls to be submissive, the result is exactly what we saw in Munshiganj. Rage, directed at women. Violence, disguised as discipline. Patriarchy, masquerading as family values.

So, when do we finally say enough is enough? When do we stop this madness at the root? When will Bangladesh take childhood trauma seriously? How many more girls must be beaten, raped, or killed before we recognise that the seeds of this crisis are planted in the earliest years of life? Will we continue to raise boys on a diet of dominance and entitlement and then act surprised when they grow up to abuse the women around them?

This link between early trauma and adult violence underscores the critical need to act. Children who grow up in violent homes are more likely to use violence themselves, more so because they don't know any other way. If we don't intervene, if we don't give them tools to heal, then we're not just failing them, we're perpetuating the very cycle we claim to condemn.

Organisations like the International Centre for Research on Women and MenEngage South Asia are doing the work many governments should be leading. They engage men and boys, challenge toxic masculinity, and try to build a future where gender justice is more than a buzzword.

But what about us, our society? Are we even ready to have these conversations? Or are we still too busy blaming women for the violence committed against them?

The incident involving Jihad is not an anomaly; it is a symptom of a festering disease. Unless we are willing to confront this disease at every level -- within our families, our schools, our courts, and our religious spaces -- we will continue to bury our daughters and sisters under the weight of our inaction.

So, I ask again: Will change ever truly come to Bangladesh? Or will we remain a nation where women are beaten in public while people cheer? Will we keep raising boys to believe violence is their birthright? Or will we finally teach them that true strength lies in compassion, not control?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments