A photographer looks back at 1971

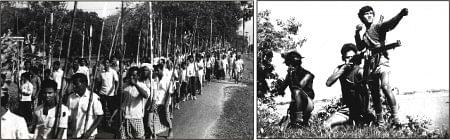

Photos taken during the Liberation War by Naibuddin. Photo Courtesy: Liberation War Museum

With great risk veteran photographer Naibuddin Ahmed captured scathing images of brutality and how people survived the terror unleashed by the Pakistani army in 1971 that helped publicise the war to the world. These images now survive as documents of the Liberation War.

Until 1971, Naibuddin was better known for his interest in rural and river scenes and the lives of ordinary people engaged in daily activities. During the war he was working as the chief research photographer of the then East Pakistan Agricultural University in Mymensingh. One day a Pakistani army personnel asked him to take a look at his camera which was not working properly. Naibuddin found the camera was working just fine, only the lance was blocked. Pretending that it was still not operating, Naibuddin took photographs of nearby houses that were burnt down and ordinary people tortured at the camp. He then packed the camera and asked the army officer to send it to his house so that he can try to fix it with necessary tools. The camera was sent to him the following day and Naibuddin kept the reel to himself. The reel was developed and with the help of a friend Shahadat, Naibuddin managed to send the photographs to Colonel Taher, commander of Sector 11. Taher send the imaged to India.

When one of the photographs was published in the Washington Post, the Pak intelligence went mad. The photograph damaged the occupying force's claim of “normalcy” as it exposed the general atmosphere of terror that prevailed everywhere. The international community was already outraged by the news of genocide. The Pakistani army searched every nook and corner of Naibuddin's house. They even went through his books but could not find the negatives, says the photographer.

Whenever Naibuddin heard some news of carnage, he would go out there with his camera. He mainly worked within Sector 11. Some of his moving images capture the sufferings of women at the hand of the Pakistani army and their henchmen. Naibuddin's images recount the atrocities unleashed on the ordinary people struggling for freedom.

Together with friends, he also formed a group to help the freedom fighters with money and medicine.

“Bangobandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's call to fight the enemy in whichever way possible, gave me the strength to move forward with my camera,” says Naibuddin.

The photographer gets frustrated when he sees that the perpetrators of the genocide are not being tried and are living openly among us, some of them flaunting political power.

“The emergence of Bangladesh as a sovereign state represented the implication of certain principles, but after 36 years one wonders if we have been able to execute and establish those principles at all. The young generation needs these principles as a guiding light. Each activity and aspect, including photography, should reflect that state of mind. We need to inspire our youngsters with the spirit that led a more or less unarmed nation to engage in a do-or-die struggle against one of Asia's most well-equipped and trained military forces,” Naibuddin says.

Naibuddin had his first camera in 1942. He exhibited his works for the first time in 1954 at USIS. He stopped taking photographs after the Liberation War.

Ahmed Zaki made a documentary titled "71: In Frame and Out of Frame," celebrating the photographer's works during the war. The documentary was produced by the audio-visual centre of the Liberation War Museum.

The article is a reprint of an earlier version

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments