“Muraqqa”: Imperial Mughal albums

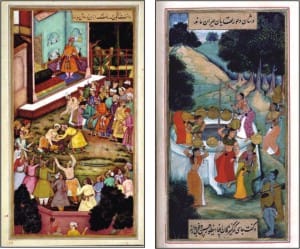

"Akbar Fights with Raja Man Singh," from a copy of the Akbarnama. (circa 1600-03)and "The Women at the Well of Kanchinpur," a manuscript made for Prince Salim. (circa 1603-04)

Muraqqa is the Farsi term for a patched garment traditionally worn by Sufi mystics as a sign of poverty and humility. Yet it is also the word for a gilded and lavishly calligraphed album. This type of muraqqa, a luxury object from the Mughal empire in India, is a patchwork of imagery: portraits of emperors and courtiers, Eastern mystics and Western religious figures; examples of plant and animal life.

For just two more weeks muraqqa commissioned by the Mughal emperors Jahangir (ruled 1605-1627) and his son Shah Jahan (ruled 1627-1658) will be on view at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution. “Muraqqa: Imperial Mughal Albums” showcases 82 rarely seen paintings from six albums. These muraqqa are indeed patchworks, of the most elegant and refined variety.

Accompanied by an informative (and, at 528 pages, intimidating) catalogue, the show inaugurates a yearlong festival of India-related programming at the Sackler and Freer Galleries of Asian art that will include performances, films and an exhibition in the fall titled “Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur.”

The works in “Muraqqa” were collected by the American-born industrialist and philanthropist Alfred Chester Beatty (1875-1968), who established a library in Dublin for these and other treasures. One imagines that Beatty, a mining magnate, was drawn not only to the jewel tones and gilded surfaces of Mughal paintings, but also to their intimations of empire.

Formal and informal portraiture, naturalism, spirituality, worldly extravagance and history are condensed into images no bigger than a notebook. (The museum has thoughtfully provided magnifying glasses.) A typical album is composed of folios, or double-sided sheets, made up of several layers of paper pasted together. Each folio pairs a painting with a section of calligraphy, both surrounded by decorative borders; the relationship of image and text varies from illustration to loose association.

While the paintings in “Muraqqa” are by many different artists, much of the text can be credited to the famed calligrapher Mir Ali of Herat, who often signed his works in abject fashion, “the sinful slave Mir Ali the scribe” or “the poor Ali.” His voice, sometimes plaintive and sometimes mocking, is as distinct as his handiwork.

The albums represented in “Muraqqa” are scattered among different public and private collections; the works at the Sackler are only fragments. Sections of one album, known as the Late Shah Jahan album, passed through the hands of an unscrupulous early-20th-century French dealer, Georges Demotte, who separated the folios to maximise his profits. Another album was altered while in the possession of the Qajar ruler of Iran, Nasir al-Din Shah, for whom it is named. In almost all of the folios on view, the colours remain nonetheless startlingly vibrant.

The muraqqa mirror the tastes and interests of the emperors who commissioned them. Art from Jahangir's reign combines Persian, Indian and Western imagery and includes abundant references to hunting and natural history. Shah Jahan, who built the Taj Mahal, favoured formal portraiture and court scenes teeming with flowers and jewels.

The earliest of the muraqqa on view is the Salim album, commissioned while Jahangir's father, Akbar the Great, was still in power. Reflecting Jahangir's religious curiosity, it includes portraits of Hindu courtiers and visiting Jesuits, and a striking image of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child that was probably influenced by the Christian images the Jesuits brought to Akbar's court.

The young Jahangir also commissioned an album called the “Shikarnama,” or “Hunting Book.” In the sole “Shikarnama” folio on view Prince Salim (the future Jahangir) has killed a rhinoceros and a lioness. The painting is a frenzy of activity, with the prince astride an elephant in the foreground and a cheetah battling an antelope in the background. In the center an attendant holds up the head of the dead lioness for inspection.

Bridging the reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan are 19 folios from the Minto album, a collection of 40 folios currently divided between the Chester Beatty Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Among the most lavish in the show, these folios are distinguished by elaborate, gilded borders of flowering plants.

In many portraits from this album the emperor (sometimes Jahangir, sometimes Shah Jahan) is holding a small globe in his hand or standing atop a larger one. One richly allusive painting shows Jahangir balancing on a globe as he shoots an arrow into the decapitated head of a rival ruler, Malik Ambar. An evocative inscription reads, “Whenever you come into the bow you steal the colour from the cheeks of enemies.”

Royal entourages, often shown in outdoor settings, are another Minto theme. In one spectacular example depicting an Islamic garden in Western-style perspective, a colourfully attired prince and his courtiers drink wine from Venetian goblets.

Folios produced under Shah Jahan are more formal than natural, with much attention paid to clothing as a sign of rank or religious discipline. One courtier wears a cloak with an extraneous pair of sleeves, and an ascetic has a tiger skin draped over his shoulder.

In a portrait that hangs in the final gallery of the exhibition the Sufi Shaykh Shah Dawlat wears a short patched shawl. The garment's colours echo the red-and-yellow border of the painting, linking one type of muraqqa to another. A preface by Mir Ali, reproduced in the catalogue, comes to mind: “As long as the patched cloak of the celestial sphere contains the sun and moon, may this album be the object of your perpetual gaze.”

Source: The New York Times

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments