Marine fisheries management

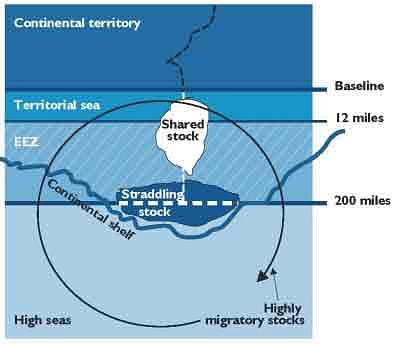

Simplified diagram of maritime zones and distribution of shared, straddling and highly migratory stocks as defined by UNCLOS - in articles 63(1), 63(2) and 64. Photo: fao

In contemporary ocean governance, management of marine fisheries, the most valuable among all oceanic living resources, has been given due priority in view of the fact that marine fisheries account for nearly 85% of the global fish catch. In addition, marine fisheries play an important role in the global provision of food, supply of least 15% of animal protein consumed by humans and indirectly supporting food production by aquaculture and livestock industries. However, the dilemma that the marine fisheries management has been facing so long is the issue of exploitation versus conservation. Needless to mention, principles and extensive regulatory arrangements for the management of marine fisheries on the ideals of preservation, conservation and sustainable exploitation have been clearly detailed out in Part V (EEZ) of the UNCLOS 1982. Alongside the normative principles of UNCLOS, various international initiatives (UN Code of Conduct for Responsible Fishes FAO, Convention on Biological Diversity, Millennium Ecosystem Assessment etc.) have been taken to promote optimal utilisation of marine fishes, save the marine fish stocks from deleterious ecological and socio-economic consequences etc. Unfortunately, the extent to which the maritime nations are abiding by such restrictive principles of fisheries management remains unknown. While principles have been laid down, strong differences of opinions as to their meaning and implementation continue to persist.

As a result, global marine fishery is now in a state of crisis. An estimated 70% of the world's fish stocks are already being exploited at or beyond sustainable limits. Global marine fisheries land-up has decreased by about 1.7 million tones per year since late 1980s, with at least 28% of the world's fish stocks being overexploited or depleted and 52% fully exploited by 2008. The threat of unabated fishing continues with the tendency to increase more in the future. The reasons that explain this are rapidly increasing human population, escalating animal protein demand, destructive fishing methods, use of fish for medicinal purposes, labeling fish as 'health food,' use of fish for pet food industry and animal feed, wastage as 'by-catch' etc.

With respect to marine fishing, it is to be noted that most of the fishing in coastal states is concentrated in inshore waters near the coast, territorial waters and lastly in the EEZ. Among these, EEZ is the most resource base area in terms of possession of both living and non-living resources. While it is true that extended maritime zones as per the UNCLOS 1982 have benefited a number of coastal states, the fact remains that 80% of the world fish catch in the EEZ is still taken by not more than 20 fishing nations. These nations are the ones endowed with modern marine technology, equipments and tools. The rapacious fishing by a handful of privileged maritime nations failed to take into consideration the fact that even the largest EEZ is not a self-contained management unit. It is an area where the fishes originate in the zone and as well house those coming from the high seas. If resources and the environment are not managed beyond the 200 mile limit, they can not be managed effectively within the zone either. It is in this context that the negotiations on straddling and highly migratory fish (SHMF) ultimately led to the United Nations Agreement for the Implementation of the Provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 relating to the Conservation and Management of Straddling Fish stocks and Highly Migratory Stocks. The agreement is basically an expansion of Section 2 of Part VII (High Seas) of the Law of the Sea Convention, extending to the high seas the principles of conservation and management contained in part V (EEZ) and adding many of the useful details contained in Chapter 17 of Agenda 21 (Agenda 21 of UNCED 1982 is a comprehensive plan of action for the 21st century covering all sectors of socio-economic activity, contains a chapter specifically devoted to world's oceans and seas. The chapter identifies seven major programme areas, of which sustainable use and conservation of living resources of the high seas is one.). Before undertaking a further discussion on SHMF, it is pertinent to define these two species of fish. Straddling fishes are those that migrate within the EEZ of two or more coastal states or in areas adjacent to the zone or beyond it. Highly migratory fish species are those that undertake migration in wide oceanic regions for the purpose of food, reproduction or averting any ecological disturbance. Highly migratory species are well listed in Annex I of UNCLOS where fishes like tuna, sword fish, pomfrets figure prominently.

'The Agreement sets out principles for the conservation and management of SHMF stocks and establishes that such management must be based on the precautionary approach and the best available scientific information. The Agreement elaborates on the fundamental principle, established in the convetion that should cooperate to ensure conservation and promote the objective of the optimum utilisation of fisheries resource both within and beyond the EEZ. The Agreement attempts to achieve this objective by providing a framework for cooperation in the conservation and management of those resources. It promotes good order in the oceans through the effective management and conservation of high seas resources by establishing, among other things, detailed minimum international standards for the conservation and management of SHMF; ensuring that measures taken for the conservation and management of these stocks in areas under national jurisdiction and in the adjacent high seas are compatible and coherent; ensuring that these are effective mechanisms for compliance and enforcement of those measures on the high seas; and recognizing the special requirements of developing states in relation to conservation and management as well the development and participation in fisheries for the two types of stocks mentioned above.'

The essence of the Agreement on SHMF is the enmeshing of management of fishes living in two separate zones -- one within the national jurisdiction of a coastal state whereas the other is outside any such jurisdiction, the high seas. This was an effort built on three pillars: the introduction of responsible fishing, sustainable development with a view to introduce an environmental reference point, and the control of activities by means of regional or international arrangements. In the agreement, therefore, there is the fundamental recognition that: (i) it is impossible to manage fisheries within even the largest EEZ if they are not equally managed beyond the limits of EEZ; (ii) the two management systems must be properly integrated; (iii) regional cooperation and organisation (if needed international arrangements) are to play a crucial role in the management of the fisheries of the high seas and (iv) port states' responsibilities are extended from enforcement of environmental regulations to fisheries regulation.

It should be borne in mind that the Agreement on SHMF mainly targets those nations whose marine capacity allows them to fish in nearly all segments of oceans, let alone the areas like EEZ, the territorial sea etc. Bangladesh, as of now, has not been fully capable of exploiting its fish resources in the EEZ. Nonetheless, the country should be aware about the exploitation of fishes in its EEZ and the adjacent areas by countries like India Myanmar and Sri Lanka. The mentioned countries are well equipped to fish even in the high seas. As a result, Bangladesh's EEZ that overlaps with the EEZs of India and Sri Lanka respectively should be concerned about the SHMF that move in the interconnected waters. In this connection, the most practical step would be to go for some kind of a regional arrangement.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments