Treaty of Versailles 100 years on

The First World War was contemporaneously described as "the war to end all wars". However, as we look back now, we see that it was just the beginning of what was one of the (if not the) bloodiest centuries in human history, and a reason for that is, as the saying goes, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

One way we remember the past is through history. But what we forget is that the histories of wars have been written by their victors, which means that history often depicts their writers in a more favourable light than how they should be depicted. This warping of history prevents it from communicating lessons that nations and civilisation must learn to not repeat the past mistakes that led to wars. While populations are frequently manipulated into wars using lies, history of why past wars were fought, when falsified, also ensures that populations can be lied into future wars. It is only through this understanding that we can comprehend the true nature of the First World War.

Today, the notion that the First World War was fought between imperialistic powers on the one side and democratic forces on the other, still exists. And in some countries, the idea that the war was primarily a struggle between those who believed in the ideals of liberty, versus those who were strictly authoritarians, still gets pushed into the mainstream. However, the truth is, the First World War was the eventual outcome of different nations trying to either retain their position as the dominant imperialistic power in the world, or to become so. And it is for this reason that an estimated 40 million people died directly from the First World War, and millions of other lives were lost from conditions given rise to by it.

Although much of the common narrative seeks to put the blame for the war on the shoulders of the German nation, and Article 231 in the Treaty of Versailles—the treaty that ended the war between Germany and the Allies—also known as the War Guilt Clause, blamed Germany entirely for starting the war, the truth is actually much different. But to uncover it, we must go back to before the war started.

The German Reich was created after Prussia won the Franco-Prussian War in 1871. This led to a tremendously more powerful Germany, with much greater economic and industrial strength, at the centre of Continental Europe. Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz and German Emperor Wilhelm II sought to use this new industrial strength to create a powerful Imperial German Navy to compete with Britain's Royal Navy, which at the time was the world's supreme naval power—inspired by US naval strategist Alfred Mahan, who argued that whoever ruled the sea, would also rule the world.

Before the turn of the 20th century, Germany had surpassed Britain in both the rate and quality of technological development as German total domestic output increased five-fold from 1850-1913 and per capita output by 250 percent. In 1890, Germany produced 88 million tonnes of coal while Britain produced more than double that at 182 million tonnes (The German Economy, 1870 to the present, Gustav Stolper, Karl Hauser, Knut Borchardt). By 1910, German coal output reached 219 million tonnes, leaving Britain with only a slight lead at 264 million tonnes. Between 1880 to 1900, German steel output increased by 1,000 percent leaving British steel output far behind. And by 1913, Germany was smelting almost double the amount of pig iron as British foundries. This led the British elite to increasingly see the industrial emergence of Germany as the biggest threat to Britain's global hegemony.

The "clash of interests" between the two became unbridgeable when German banking and political circles decided to build a rail-link that would connect Berlin with the Ottoman Empire as far as Baghdad and then onto Mesopotamia. The stakes went up as Britain secured exclusive rights to Persian oil and in 1909, established the Anglo-Persian Oil Company after discovering oil there in 1908. A German-built rail link to the Persian Gulf, capable of carrying troops and armaments, was an enormous strategic threat to British oil interests in the region. Major RGD Laffan, who was in charge of a British military training mission in Serbia just before the war, wrote: "If 'Berlin-Baghdad' were achieved, a huge block of territory producing every kind of economic wealth, and unassailable by sea-power would be united under German authority...German and Turkish armies would be within easy striking distance of our Egyptian interests, and from the Persian Gulf, our Indian Empire would be threatened."

Similarly, in 1915, British MP Noel Buxton wrote: "No one now denies the supreme importance of the Balkans as a factor in the European War. It may be that there were deep-seated hostilities between the Great Powers which would have, in any case, produced a European War, and that if the Balkans had not offered the occasion, the occasion would have been found elsewhere" (The War and the Balkans). Nevertheless, the Balkans did provide the occasion on June 28, 1914, when Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo.

After the assassination, the British government deceptively told Austria-Hungary that they accepted its right to compensation from Serbia. Thus, when Austria delivered its July ultimatum to the Serbs—a series of demands that were intentionally made unacceptable—it only expected a local war to result. But the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov, who had deep ties with the British, responded by mobilising Russian forces on July 28 against the wishes of the Tsar (Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War, Docherty and MacGregor). What neither Austria-Hungary nor its German ally realised was that the assassination of the Archduke had been orchestrated by the Serbs with the encouragement of British agents in the Russian government (ibid). In the 1917 court case on the assassination, Serbian colonel Dragutin Dimitrijevic confessed that he hired Ferdinand's assassins and that the murder was planned with the knowledge and approval of the Russian Ambassador in Belgrade, Nicholas Hartwig, and the Russian military attaché in Belgrade, Victor Artamonov.

Even as the Russian and German armies were marching out on July 1, the Tsar and the Kaiser were exchanging telegrams in a final attempt to avoid war. Later on that same day, the Kaiser wrote: "I have no doubt about it: England, Russia and France have agreed among themselves to take the Austro-Serbian conflict for an excuse for waging a war of extermination against us...the net has been suddenly thrown over our head, and England sneeringly reaps the most brilliant success of her persistently prosecuted purely anti-German world policy against which we have proved ourselves helpless. We are brought into a situation which offers England the desired pretext for annihilating us under the hypocritical cloak of justice."

The Kaiser was, at least partially, correct. In the book, De Gaulle: His Life and Work, Nikolai Molchanov points to how the French were thirsting for revenge during this time against the Germans following its humiliating defeat back in the war of 1871. A number of indications showed that the French were preparing for war, including the passage of a law in 1913 that increased compulsory military service in France from two to three years in the hopes that it would bridge the gap in the numbers of the German and French armies. Things were finally brought to a head when Raymond Poincare, known for his hawkishness, was elected as French president in 1913.

As tensions flared, Poincare, in a visit to St Petersburg, guaranteed Russia that, "France would not only give Russia strong diplomatic support, but would, if necessary, fulfil all the obligations imposed on her by the [Triple Entente] alliance." On July 29, Tsar Nicholas II officially ordered Russian mobilisation, but then received a telegram from the Kaiser which said: "My ambassador is instructed to draw the attention of your government to the dangers and serious consequences of a mobilisation. If, as appears from your communication and that of your Government, Russia is mobilising against Austria-Hungary...The whole burden of decision now rests upon your shoulders, the responsibility for peace or war." This persuaded the Tsar to back down. The next day, Russian Foreign Minister Sazonov convinced the Tsar that Germany was plotting a betrayal, urging him to reorder the mobilisation of the army. According to the French ambassador, "The Czar was deadly pale and replied in a choking voice: 'Just think of the responsibility you are advising me to assume! Remember, it is a question of sending thousands and thousands of men to their death.'" Ultimately, however, the Tsar reluctantly obliged.

Russia's rival at the time, the Ottoman Empire, similarly feared the growing influence of the Germans and had made three separate attempts to ally itself with Britain only to be rejected on each occasion (Gallipoli, Robert Rhodes James). The Ottomans also tried to ally with France on condition that the French would protect the Ottomans from its old enemy, Russia, but in vain (Studies in Secret Diplomacy, WW Gottlieb). The main reason for British and French hostility towards the Ottomans was because they planned to use the worn-down empire to coerce Russia to be on their side.

In July 1914, when the majority of the Turkish cabinet still looked favourably upon the British, the British decided to seize two of its battleships that were being built in England in order to please the Russians. According to Gottlieb: "If Britain wanted deliberately to incense the Turks and drive them into the Kaiser's arms she could not have chosen more effective means." The decision was meant to be a direct provocation that would leave the Ottomans with no other choice but to side with the Germans—hence guaranteeing that Russia would take an anti-German stance because of its rivalry with the Ottomans, who were now forced to side with the Germans.

According to Harvey Broadbent, Senior Research Fellow in the Department of Modern History at Macquarie University, evidence for this could be found in a secret treaty that was agreed in February-March 1915 between the British and the Russians ("Gallipoli: one great deception?", ABC News). As per the treaty, the British and French governments promised that after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, "there would be annexation to Russia 'of the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles; Southern Thrace up to the line of Enos-Midia; the coast of Asia Minor between the Bosphorus, the River Sakaria and a point along Ismit Bay; subject to latter determination the islands of Imbros and Tenedos'." But after the Bolsheviks seized power, a war-weary Russia was forced to sign the Brest-Livotsk treaty with Germany on March 3, 1918, surrendering its imperialistic plans and ambitions.

Because of Germany's extravagant demands from the Russians at Brest-Livotsk, which stretched out the negotiations, German transfer of soldiers from the eastern to the western front did not happen fast enough. And the occupation of the vast territories that Russia was forced to give up meant that Germany had to keep approximately a million men stationed there. Here we see Germany displaying the same tendency of enforcing the severest of punishments and demanding the most excessive compensation from its defeated opponent, as the Allies later would, in the Versailles Treaty.

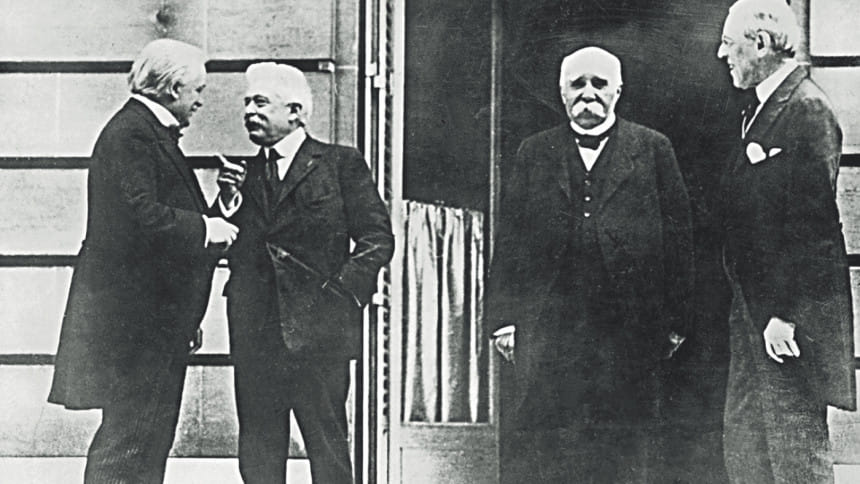

The First World War ended in November 1918. But the Treaty of Versailles was signed much later in June 1919. For the first six months of 1919, Britain's Lloyd George, France's Clemenceau and the US's Woodrow Wilson met in Paris to hammer out the peace terms they would impose on Germany. According to Serbian author Dragan Plavsic, they had three broad aims: i) To make Germany pay for the war and to neutralise it as a competitor power; ii) To counter the revolutionary wave set off by the Russian Revolution of 1917, i.e., maintain the same power structure that existed in their respective countries before the war; and iii) To ensure that the resulting peace terms were as compatible with their own competing interests as possible.

According to American historian, Michael S Neiberg, the initial reparations bill demanded by the Allies was, in a word, "crippling" (The Treaty of Versailles: A Very Short Introduction). By 1926, Germany had to pay 60 billion gold marks which was an amount equal, according to some estimates, to the country's national income for one whole year. For 15 years, Germany's coal producing Saar district was to be occupied by Britain and France—under the authority of the League of Nations—and its mines would be ceded to France. While for 10 years, Germany had to deliver an annual average of 25 million tonnes of coal to France, Belgium, Italy and Luxemburg; and the list goes on.

The famous economist John Maynard Keynes, who participated in the Paris Peace Conference only to leave in disgust, described the negotiations as "so contorted, so miserable, so utterly unsatisfactory" that no one could look back on it "without shame". He explains that Clemenceau wanted to "crush the economic life of his enemy"; Lloyd George wanted to punish Germany without unbalancing Europe in France's favour; and Wilson wanted to expedite the repayment of American war loans by Britain and France. However, in their blind and narrow pursuits, the three leaders completely ignored the economic questions that would come back to haunt Europe through the rise of Hitler, who promised Germans relief from the economic strife imposed upon them after the defeat in the First World War.

To make matters worse, the Allies famously enshrined German war guilt as one of its clauses in the Versailles Treaty. And Belgian historian Laurence Van Ypersele describes the central role played by the memory of the war and the Versailles Treaty in German politics in the 1920s and 1930s in these words: "Active denial of war guilt in Germany and German resentment at both reparations and continued Allied occupation of the Rhineland made widespread revision of the meaning and memory of the war problematic. The legend of the 'stab in the back' and the wish to revise the 'Versailles diktat', and the belief in an international threat aimed at the elimination of the German nation persisted at the heart of German politics" (A Companion to World War I). It is under these conditions that "[Hitler's] Nazi Germany sought to redirect the memory of the war to the benefit of its own policies."

It was in similar search for revenge that the treaty between the Allies and Germany was signed in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles. The French had decided on that venue to obtain some symbolic payback "for the fact that it was from that same room that the German Reich had been proclaimed in January 1871, during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871" (The Great Class War 1914-1919, Jacques R Pauwels).

In an identical manner, the treaty signed in Versailles in 1919 would only prove to be the precursor to another devastating world war, as while the victors busied themselves with revisioning history to suit their own interests, the lessons of war were once more left abandoned and unlearned. Condemning those who couldn't remember the bloody past, to once again repeat it.

Eresh Omar Jamal is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. His

Twitter handle is: @EreshOmarJamal

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments