The early history of press freedom in Bengal

In mid-eighteenth century Mughal India, slowly but surely, the old was giving way to the new in complex ways. The Mughal Empire was losing its influence, while the EIC gained political power and influence after the Battle of Plassey (1757), Battle of Buxar (1764) and the Treaty of Allahabad (1765), in which the Mughal Emperor formally acknowledged British dominance in the region by granting EIC the diwani, or the right to collect revenue, from Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The Supreme Court was founded in Calcutta in 1774. The EIC ceased to be simply a trading company and transformed into a powerful imperial agency with an army of its own, exercising control over vast territories with millions of people. As Thomas B. Macaulay said during a speech in the House of Commons on 10 July 1833: "It is the strangest of all governments; but it is designed for the strangest of all empires". Elsewhere, the close of the eighteenth century was a period of cataclysmic change: American and French Revolutions had a profound influence not only on rulers in England but also on officials of the EIC. Radical politics began to emerge in England from the 1750s, which was strongly resisted by the forces of status quo. The same fears gripped the early officers of the expansionist EIC as it established itself in Calcutta and spread its influence across India.

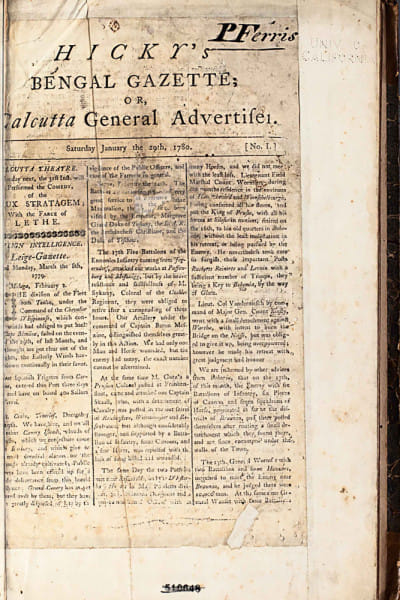

Journalism emerged amidst such conditions and uncertain attempts by the Company government to introduce new, modern ways of governance and other measures, most of which proved controversial and faced opposition from Indians. The Company government, at the time engaged in battles across India, watched uneasily as English-language journals were launched from 1780 onwards, when James Augustus Hicky published the first journal, Hicky's Gazette Or Calcutta General Advertiser. Alert to the dangers of Jacobinism, the EIC tried to control the press and prevent its growth from as early as 1799, by when British entrepreneurs and agency house came together to launch more journals. The question of freedom of the press first exercised colonial authorities at the time of Richard Wellesley's governorship (1798–1805), when the Company government interpreted any criticism in journals as lurking Jacobinism. In 1799, Wellesley introduced regulations for the press, which stipulated that no newspaper be published until the proofs of the whole paper, including advertisements, were submitted to the colonial government and approved; violation invited deportation to England. Until 1818, the regulations applied only to the English journals, because until that year, there were no journals in Indian languages.

The Company government succeeded in controlling the press until 1818, by when the combination of a proliferating commercially driven print culture, a growing British community, a new generation of British editors and administrators, Christian missionaries and Indian elites alert to new ideas and impulses, ensured the growth of journalism and the idea of a free press. Several English-language journals followed Hicky's journal.

If Hicky's journal is better known historically for publication of scandals, scurrilous personal attacks and risqué advertisements selling sex and sin, he was also the first to fight against the colonial government, then almost single-handed, to defend the liberty of the press. He wrote: "Mr Hicky considers the Liberty of the Press to be essential to the very existence of an Englishman and a free G-t. The subject should have full liberty to declare his principles, and opinions, and every act which tends to coerce that liberty is tyrannical and injurious to the COMMUNITY" (Barns 1940, 49, italics and capitals in original; in the days of letter press, "G-t" stood for "Government"). Hicky was soon hounded by Hastings and Impey, fined, imprisoned and his journal closed in March 1782. He died in penury in 1802.

By 1800, some journals closed for want of advertising and subscription, while others closed when British editors were deported to England after publishing material that was considered unacceptable by the EIC. Editors who attracted EIC's ire and found themselves on ships back to England included William Duane, editor of Bengal Journal, removed as editor and almost deported in 1791, and finally deported as editor of Indian World in 1794; Charles Maclean, editor of Bengal Hurkaru, deported in 1798; James Silk Buckingham, editor of Calcutta Journal, and his assistant, Sandford Arnot, deported in 1823; and C. J. Fair, editor of Bombay Gazette, also deported in 1823.

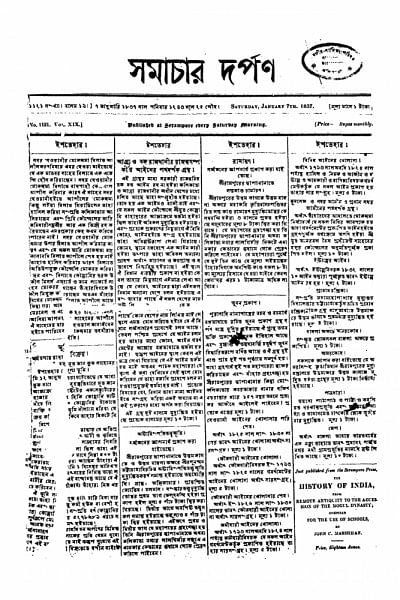

The year 1818 had witnessed developments that catalysed the growth of journalism in an expanding colonial India. As noted above, deportation remained a key instrument to discipline British editors, but the measure could not be applied to editors who were Indians or to Europeans born in India. To remove the anomaly, the Marquess of Hastings, who was governor-general from 1813 to 1823, removed the 1799 censorship and issued a new set of rules in 1818. In a circular to all editors and publishers in Calcutta, he set out guidelines with a view to prevent the publication of topics considered dangerous or objectionable, or face deportation. But his new rules did not possess the force of law as they were not passed into a Regulation in a legal manner, which meant that in practice there were no legal restrictions on the press. The Marquess of Hastings was soon hailed in Calcutta as a liberator of the press. In the same year, the first journals in an Indian language—Bengali—were launched, the precursors of several Indian-language journals in other parts of India. There is a dispute about which was published first, the Bengal Gejeti edited by Harachandra Roy with the assistance of Gangakishore Bhattacharya, or Samachar Darpan, launched by the Baptist missionaries at Serampore—both were launched in May 1818 (some scholars claim that Bangal Gejeti was launched in 1816).

The year 1818 also saw the launch of Buckingham's Calcutta Journal, on 2 October, a biweekly of eight quarto pages, which was to come into frequent conflict with EIC and also encourage the growth of the indigenous press by often publishing extracts from the Indian-language journals and commenting favourably on their growth. A Whig, Buckingham propagated liberal ideas and views through his journal that almost reached the record daily circulation figure of 1000 copies. As the editor, he wrote, he conceived his duty to be "to admonish Governors of their duties, to warn them furiously of their faults, and to tell disagreeable truths" (Barns 1940, 95). Setting himself up as a champion of free press, Buckingham saw a free press as an important check against misgovernment, especially in Bengal, where there was no legislature to curb executive authority.

Print journalism had found a fertile soil in colonial Calcutta, but it also generated near-panic among colonial officials about its potential subversive effect on the army. Expressing "intense anxiety and alarm", Chief Secretary John Adam (1822) wrote in a lengthy minute on the press: "That the seeds of infinite mischief have already been sown is my firm belief". When the Marquess of Hastings sailed for England on 9 January 1823, he was temporarily succeeded as governor-general by John Adam, whose first act was to deport Buckingham to England, which led to the closure of Calcutta Journal. Secondly, Adam promulgated a rigorous Press Ordinance on 14 March 1823, which made it mandatory for editors and publishers to secure licences for their journals. To secure the licences, they had to submit an affidavit to the chief secretary under oath. For any offence of discussing any of the subjects prohibited by law, the editor or publisher was liable to lose the licence.

The following sections set out the Indian response to the Press Ordinance, mainly directed by Rammohun Roy (1772–1833), who is less known for his contribution to Indian journalism than for his reformist initiatives in the realm of religion, education and social awareness (in particular, for his campaign to abolish sati or widow burning).

Roy was closely associated with at least five journals: Bengal Gejeti (Bengali, 1818), The Brahmunical Magazine (English–Bengali, 1821), Sambad Kaumidi (Bengali, 1821), Mirat-ul-Akhbar (Persian, 1822) and Bengal Herald (English, 1829). Roy—easily one of the foremost examples of an "argumentative Indian" (Sen 2005)—often engaged in lengthy debates with Baptist missionaries and used his polemical skills to oppose the Press Ordinance.

Adam's Press Ordinance was submitted to the court on 15 March 1823, and two days later, Rammohun Roy and four others submitted a memorial, asking the court to hear objections against it. Besides Roy, it was signed by three Tagores (Chunder Coomar, Dwarkanath, Prosunno Coomar), Hurchunder Ghosh and Gowree Churn Bonnergee.

The memorial discussed in a logical manner the general principles on which the claim of freedom of the press was based in all modern countries, and recalled the contribution Indians had made to the growth of British rule. It created a sensation at the time and came to be described as the "Aeropagitica of Indian history" (Collet 1988, 180, italics in original). The memorial pointed out the aversion of Hindus to undertaking an oath because of "invincible prejudice against making a voluntary affidavit, or undergoing the solemnities of an oath". Using the rhetorical strategy of professing loyalty and attachment of the Indians to British rule, the memorialists wrote that they were "extremely sorry" to note that the new restrictions would put a "complete stop" to the diffusion of knowledge, promoting social progress, and keeping government informed about public opinion. It pointed out that the natives "cannot be charged with having ever abused" freedom of the press in the past, and went on to audaciously state:

The memorial was read in court, but the judge, Francis Macnaghten, dismissed it, but admitted that before the Press Ordinance was entered or its merits argued in court, he had pledged to the government that he would sanction it. The ordinance was registered in the court on 4 April 1823. The memorial was much appreciated but failed to prevent the ordinance from becoming law. The only other recourse Roy and his group had was to appeal to the King-in-Council in London. Roy then drafted another memorial, more sophisticated in its logic and arguments, and sent copies to Lord Canning (then Foreign Secretary and Leader in the House of Commons) and to the EIC's Board of Control, in London. Over 55 numbered and lengthy paragraphs, Roy repeated the opposition to the Press Ordinance.

Continuing the rhetorical strategy of mixing fulsome praise with caution, warning and criticism, the second memorial recalled world history and put it to the King:

Men in power hostile to the Liberty of the Press, which is a disagreeable check upon their conduct, when unable to discover any real evil arising from its existence, have attempted to make the world imagine, that it might, in some possible contingency, afford the means of combination against the Government, but not to mention that extraordinary emergencies would warrant measures which in ordinary times are totally unjustifiable, your Majesty is well aware, that a Free Press has never yet caused a revolution in any part of the world because, while men can easily represent the grievances arising from the conduct of the local authorities to the supreme Government, and thus get them redressed, the grounds of discontent that excite revolution are removed; whereas, where no freedom of the Press existed, and grievances consequently remained unrepresented and unredressed, innumerable revolutions have taken place in all parts of the globe, or if prevented by the armed force of the Government, the people continued ready for insurrection. (Collet 1988, 407)

A key aspect of the memorial was Roy's recall of Mughal history and the akhbarat (newsletters) system instituted during their rule. In two paragraphs (43 and 50), the memorial regretted the new press restrictions, made veiled criticism of British rule and stated:

Your Majesty is aware, that under their former Muhammadan Rulers, the natives of this country enjoyed every political privilege in common with Mussalmans, being eligible to the highest offices in the state, entrusted with the command of armies and the government of provinces and often chosen as advisers to their Prince, without disqualification or degrading distinction on account of their religion or the place of their birth … Notwithstanding the despotic power of the Mogul Princes who formerly ruled over this country, and that their conduct was often cruel and arbitrary, yet the wise and virtuous among them, always employed two intelligencers at the residence of their Nawabs or Lord Lieutenants, Akhbar-navees, or news-writer who published an account of whatever happened, and a Khoofea-navees, or confidential correspondent who sent a private and particular account of every occurrence worthy of notice; and although these Lord Lieutenants were often particular friends of near relations to the Prince, he did not trust entirely to themselves for a faithful and impartial report of their administration, and degraded them when they appeared to deserve it, either for their own faults or for their negligence in not checking the delinquencies of their suordinate officers; which showed that even the Mogul Princes, although their form of Government admitted of nothing better, were convinced, that in a country so rich and so replete with temptations, a restraint of some kind was absolutely necessary, to prevent the abuses that are so liable to flow from the possession of power. (Collet 1988, 413, 416–417)

Roy took another daring step at the time: closing his Persian journal, and setting down the reasons for doing so in its last edition.

On 4 April 1823, the day the Press Ordinance was registered in the Supreme Court and became law, Roy closed Mirat-ul-Akhbar in protest. In the final issue, he set out the reasons for doing so:

Under these circumstances, I, the least of all the human race, in consideration of several difficulties, have, with much regret and reluctance, relinquished the publication of this Paper (Mirat-ool-Ukhbar). The difficulties are these:

First—Although it is very easy for those European Gentlemen, who have the honour to be acquainted with the Chief Secretary to Government, to obtain a License according to the prescribed form; yet to a humble individual like myself, it is very hard to make his way through the porters and attendants of a great Personage; or to enter the doors of the Police Court, crowded with people of all classes, for the purpose of obtaining what is in fact, already [? Unnecessary] in my own opinion. As it is written—

Abrooe kih ba-sad khoon i jigar dast dihad

Ba-oomed-I karam-e, kha'jah, ba-darban ma-farosh

(The respect which is purchased with a hundred drops of heart's blood

Do not thou, in the hope of a favour, commit to the mercy of a porter).

Secondly—To make Affidavit in an open court, in presence of respectable Magistrates, is looked upon as very mean and censurable by those who watch the conduct of their neighbours. Besides, the publication of a newspaper is not incumbent upon every person, so that he must resort to the evasion of establishing fictitious Proprietors, which is contrary to Law, and repugnant to Conscience.

Thirdly—After incurring the disrepute of solicitation and suffering the dishonour of making Affidavit, the constant apprehension of the License being recalled by Government which would disgrace the person in the eyes of the world, must create such anxiety as entirely to destroy his peace of mind, because a man, by nature liable to err, in telling the real truth cannot help sometimes making use of words and selecting phrases that might be unpleasant to Government. I, however, here prefer silence to speaking out:

Guda-e goshah nashenee to Khafiza makharosh

Roo mooz maslabat-i khesh khoosrowan danand

(Thou O Hafiz, art a poor retired man, be silent,

Princes know the secrets of their own Policy).

Taken together, even though the two memorials and closing Roy's journal were couched in courteous terms and some rhetoric, they were essentially an act of political defiance, which was delivered in the language and discourse of the new rulers. The opposition to the Press Ordinance won new converts among the British (such as Lieutenant Colonel Leicester Stanhope), and provided a template for future political opposition on other issues, such as the controversial Jury Act, Indian property and labour, the rights of Britons in India, taxes, education and making English the medium of instruction.

Roy closing his journal in protest and the two memorials did not succeed in changing policy, but their significance lies in the ways in which the colonial authorities dealt with the press subsequently. The memorials were much appreciated in England, where Buckingham had continued his campaign in print against the EIC and its exercise of arbitrary powers in India. Lord Amhurst, who took over from John Adam as the governor-general of India in 1823 (he was in office until 1828) did not implement the Press Ordinance rigorously, neither did his successor, Lord Bentinck. The memorials, closure of Roy's journal and Buckingham's activities in London had generated much publicity on the issue of freedom of the press in colonial India, with governors-general choosing to avoid taking major action against the fast growing press. In 1835, it was another acting governor-general, Charles Metcalfe, who, aided by Macaulay, removed Adam's licensing and other restrictions on the press through Act No. XI. By then, the idea of a free press had become a key element of a growing public sphere in Calcutta and elsewhere in colonial India. Metcalfe, who was later penalised by EIC authorities in London for removing the press restrictions, was hailed as a liberator of press and immortalised in Metcalfe Hall, a major landmark in Calcutta, which was built with public subscription in the style of imposing empire architecture in his honour. The press had become a key site of discussion and protest as the Company government introduced new laws and initiatives to govern India. The largely permissive situation for the press continued until the 1857 rebellion, by when opinions and positions had hardened on both sides, as Indian journals openly criticised the British and the EIC imposed new restrictions on the press.

Prasun Sonwalkar is Editor (UK & Europe), Hindustan Times.

This is an excerpt of the article titled Indian Journalism in the Colonial Crucible which was published in the Journalism Studies ( Vol 16, Issue 5, 2015).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments