Inside

|

Sheikh Mujib: Three phases, two histories, one puzzle Afsan Chowdhury

One of Sheikh Mujib's closest friends before 1947, who remained close until 1971, was a relatively unknown maverick called Moazzem Ahmed Chowdhury. Born in Sylhet, he belonged to the Communist Party of India (CPI) and led its student wing there in the 1940s. Seeing his promise, he was asked by the CPI to enter Muslim League ranks, which he did in Calcutta, and was soon a top student leader. He and his fellow worker never liked the Jinnah followers and were closer to Abul Hashim than any other. Sheikh Mujib, he mentions, always had the charisma of the supreme leader and everyone recognised that. After the Calcutta riots of 1946, when Hindus and Muslims massacred each other at will in a proxy fight between the Congress and the Muslim League, all the hopeful illusions ended. The partition of Bengal became a fact of life, especially with Muslim Bengal who voted overwhelmingly for the Muslim League in the election of 1946. It was considered a vote for "Pakistan" -- a convenient political interpretation since nobody was sure what Pakistan stood for. Not even the stalwarts of Muslim Bengal who made sure the peasants voted for a state that would brutalise them. When things settled down and partition became an unavoidable fact, Abul Hashim was shocked to find that there would be one Pakistan under the central Muslim League and not many Pakistans as the Lahore Resolution promised. Bengal's top leader H.S. Suhrawardy, who had sided with Jinnah in this one-Pakistan production, hoping for a seat in the central committee as a reward for his loyalty, ended up as his ally.

But even before Pakistan had officially come into being, a group of disgruntled young men of Bengal Muslim League met at the residence of Justice Masud in Calcutta and decided to fight to establish the independent country they thought the Lahore Resolution promised. Moazzem Ahmed Chowdhury took the lead, but there was no question about who they thought would be the leader when they planned and plotted: "We thought that only Sheikh Mujib had the charisma to be the leader. He was stubborn and not always brilliant, but he had that quality which made people follow him." The evil that bad marriages do This was, however, only half the story, because it doesn't say why the Pakistanis mistreated the Bengalis if they were part of the same state, journey, and dream. This idea of one monolithic Pakistan movement changes when one digs into the history of Bengal politics half a century earlier. It seemed that there was an independent path of "independence" of what roughly translates into East Bengal/Bangladesh territory. It was somewhat confused but strong, and was articulated even before Pakistan came into being, drawing its strength from the words of the Lahore Resolution, which they believed promised several Muslim majority provinces and not one monolithic state. Jinnah called this a typographical error, and had it changed in the book despite Abul Hashim's protest. Most leaders pinned their hope on the Lahore Resolution of March 23, 1940 calling for several "Pakistans," which many, including Bengali Muslim leaders, thought was what it said. It was even moved by a Bengali Muslim, the chief minister of Bengal, A.K. Fazlul Huq. The political spasms of 1947 to 1971 drowned the memories that existed of the robust movement of an independent state that grew and then was slapped down by history. The people who were involved seemed to have a dual personality. They were let down by Pakistan in 1947, they knew, but had somehow hoped that the new state would do them right. But when that didn't happen, they were twice shocked. Between 1940 and 1946, the scene had changed and the people were battling the central Muslim League and were talking of an independent "Eastern Pakistan," though without a high degree of specificity. Yet, the "Muslim" sentiment was their ticket to power, so the Bengal Muslim League leadership never could be entirely free of the Muslim League tag which brought them to office in the 1937 elections, although there was a lack of identity with the aspirations and structure of the Urdu-speaking leadership favoured by Jinnah. This was to cost them dearly as they shifted from one political leg to another, and history didn't wait for them to decide which was more comfortable. It decided itself, and suddenly they were tied in a very undesirable marriage called Pakistan. They thought they were going to get an independent land of their own; instead they were stuck with the old enemy within the Muslim political construct of India, who had no desire to share the spoils of a new state with Bengalis. H. S. Suhrawardy, who had done more than anyone to deliver Pakistan through the Bengali Muslim vote of 1946, also tried his hand at the United Bengal Movement, and then after 1947 found himself banned from Pakistan for several years for his pains. Sheikh Mujib: First history, second phase He left the first phase of the first history, the search for his own state within the Lahore Resolution, behind, and quickly joined the leaders who soon founded the East Pakistan version of the Bengal Muslim League, the Awami Muslim League, which later became the Awami League, in 1949. The second phase had begun. The story so far is an uncomplicated narrative of a man who longed for a new state, expected its delivery, but saw it smashed, then took the pieces and began to build his new venture in the new construction. For quite a few, Pakistan was never the goal but a mishap, something which couldn't be stated openly. It was like a forced marriage of convenience, of being part of a state they had disliked even before it was born. It was a great boon for (West) Pakistan who took pleasure in rifling the larders of Bengal because the "fish eating Hindu-loving dark-skinned Bangalees" could be fleeced in the best interest of the fair-skinned Aryan Muslim Pakistan, a marriage made in heaven for them. Sadly for them, it didn't last, either. In the last 30 years that we have followed the history of Bangladesh's public but mostly private independence war with Pakistan, there is a sense of embarrassment about how these two countries pretend to be one. There was a possibility of a third new country, another "Pakistan," where all the component states/ provinces would have got a full slate of fair socio-economic deals, but Pakistan was always the Pakistan that Iqbal and his worthy dreamers saw, a very specific dream with a specific geography.

Professor K. B. Sayeed in his book: Pakistan: The Formative Phase has written an excellent chronology of the development of the idea of Pakistan over a hundred years, and is highly recommended. In that national scheme of things, Bengal was an add-on to the idea of Pakistan. In the post-1947 Pakistan, too, it was an add-on: welcome, but as an extra bag of goodies, not as an extra mouth demanding its rightful share of the national booty. So here was this strange coupling, with one side perpetually getting the best of the other, and there seems to have been only one true believer in Pakistan as a democratic ideal: the ultimate odd man out -- Suhrawardy. And he got jailed regularly. There is very little evidence that Mujib had any feelings for the Bengali-mistreating Pakistan state. The Pakistani leadership and military, historian Ayesha Jalal has remarked in her book on the Pakistan state, just went about constructing Pakistan in splendid disregard for the East Pakistani people. Reactions to Pakistani rule probably began that very inauspicious month of August 1947, when stones of disenchantment and rage pelted the face of new Pakistan through street protests. No honeymoon for this marriage, at least. Bengal moves towards its own history Pakistan's desperation lay bare in the imposition of federal authority to remove Fazlul Huq, the old and by then increasingly moth-eaten Tiger of Bengal, on charges of having wanted the "independence of East Pakistan." This was in an interview given to a New York Times reporter with a dubious reputation. Huq had perhaps lost a step to old age, but he was still capable of understanding what constituted treason -- he was advocate general of East Pakistan, for God's sake -- the quote thus seems unlikely. Did Pakistan's authorities restore sanity or insanity by reinstating Huq, sans his election partners, and making him the home minister to boot? The man who was an alleged traitor was put in charge of catching traitors in an increasingly surreal Pakistan. The only loyal Pakistani Till his last breath it was Pakistan. Even at Kagmari, the venue where the party met and split in 1957, and Mujib physically brawled with the lefties. In 1958, when under Gen. Ayub Khan martial law was imposed in Pakistan, he remained the loyal lieutenant of Suhrawardy, who was still seeking Jinnah's posthumous approval as a soldier of Pakistan though Pakistan had decided to go full military. Suhrawardy was a believer in parliamentary democracy and constitutions and consensus, but Jinnah was never fond of such irksome obstacles, and after Pakistan's birth never proved he had serious instincts about what ailed Pakistan and now ails Bangladesh more and more every year -- a beloved dysfunctionality called political democracy.

When did Pakistan, as it was born in 1947, start dying? In 1958, by many if not most reckonings, as the military, no longer happy that they were upholding the raison d'etre of Pakistan (active hatred of India and all that comes with it) wondered why it shouldn't also do the rest. The best interest of Pakistan was the best argument to take over, and when the civilian rulers had no clout, only the army was left behind. In this case, the army was eager, willing to take charge and then teach the "bloody civilian politicians," as the crowd cheered that true patriotism always lies with military power. The civilian politicians had laid the ground and the military spread the seeds -- and the conclusion was inevitable. The East Pakistanis who were active before 1947 and the new blood that came afterwards all decided it was enough. They began to look for the other path, the older and the original road once more. The journey taken together had come to both a real and metaphorical end. The Inner Group That meant the leader -- Sheikh Mujib -- would have to leave the country and lead the insurrection from outside. He was under the impression that once a call was given many, if not all, would flock to Mujib and he would lead a victorious armada of liberation. To that end, he spent several months in Calcutta, camping out with his colleagues waiting for some murmur of coming together, but nothing occurred. He was becoming disillusioned. He wanted Nehru to meet Mujib and thought once that happened, the rest would follow. It didn't, and they all returned back to Dhaka. And soon after, 1958 happened. It made him both scared and desperate.

Taking a car to Tejgaon, driven by Reza Ali (nephew of Moazzem Chowdhury), and then a train to Sylhet accompanied by Zakir Khan Chowdhury (BNP cabinet minister as well as the brother of another minister and freedom fighter Zakaria Chowdhury), they reached the tea garden of Syudul Hasan, aristocrat socialist follower of Maulana Bhashani. "Mrs. Hasan gave Sheikh Mujib a large coat which fitted poorly, and then we walked the long way to the border. At one point, I left him, and he went ahead alone to India and to destiny." It was a misadventure, something which Moazzem Chowdhury says turned Mujib bitter towards Indian intentions. "Apparently, the IHC at Dhaka failed to deliver a message that Mujib was coming, so when he reached the Indian police station expected to be treated like a visiting leader of a state to be, he was simply arrested. By the time, the misunderstandings and all the rest were cleared up by Delhi, the matter was over. It was also no longer a secret." An angry Mujib trekked back, his feet swollen with the effort. He was arrested soon but not before he had told Moazzem that the Indians probably didn't take them seriously. Many years later on the night of March 25, 1971, as Dhaka was already burning, Moazzem Chowdhury, one of the last to see him before his arrest, asked Mujib to flee to India and lead the movement from there. He could easily arrange this, he was still in touch with the Indian intelligence, he said. Mujib looked at the burning skyline and said: "If they don't find me here, they will burn every home looking for me. And don't you remember what happened the last time. I don't trust them fully." The unknown militant It was the period when the nationalist and the leftist politicians came closest to discussing movements for a new state. The martial law in 1958 was the last knell of the bell. In Jamalpur that year, a group of young people led by one Ali Asad formed a group to establish an independent country. This clandestine group, factually speaking, was the first group formed on Bangladesh/East Pakistan soil for this purpose. This effort grew in that area, attracting young men from both Awami League and the National Awami Party (or erstwhile AL cadres). By several accounts, more than 30 people were members, including the late classical music singer Ustad Fazlul Haque, politician Abdur Rahman Siddiky, and others. This group decided that they must seek the support of the major leaders including Bhashani and Mujib. They met Abul Mansur Ahmed, who promised to deliver their message to Mujib, and they also met other leaders like Tofazzal Hossain (Manik Mia), editor of Ittefaq. They were not, however, a part of the Awami League, and didn't see the party embrace their mission. They were told to contact the authorities in India, and so they trekked there, without resources or contact. Their effort to meet Indian leaders failed, but they met some Indian Communist Party members who came from their area. These sympathetic deshi bhais raised money, and with that they printed posters and leaflets. They made their way home and put them up in prominent places or threw them in darkened cinema halls to startled audiences. Within months, however, most were caught. This attempt was not well known and has been lost from public memory. When I first discovered details of this attempt on the pages of a pile of derelict secret files, I was thrilled, because in 1978 I had never heard of it before. However, right in our office -- the 1971 Dolilpotro Project -- Imamur Rashid, also from Jamalpur, was close to them. Oli Ahad's book also refers to them in jail. Later, I came to know them, and interviewed those still around. Most were dead, and the whereabouts of the mysterious leader of this group, Ali Asad, has never been known. The last anyone knows is that he was waiting to take a flight from Calcutta to Delhi. How many know of this militant nationalist? Much of what we know about this group comes from Pakistan's Home Ministry files and the observations therein. The investigating officer's sense of shock was high. How could East Pakistanis tolerate these sorts of posters? Why was there no protest even when they were plastered on the walls of the Secretariat? Had these posters and leaflets been distributed in West Pakistan, people would have protested loudly, but not here: why? It was a question that they were not astute enough to answer, because the disease of political blindness had set in deep. The very policies that were pushing or had pushed the East Pakistanis away didn't seem unfair to those executing them. Mujib and the communists It was soon after that meeting that Mujib traveled with Moazzem Chowdhury on the fateful trip to Sylhet. But in 1962, most of the parties seemed to be contemplating independence of one sort or another, including Kazi Zafar and his young leftie friends, and they were in touch with Mujib, too. So were a gaggle of other groups, and to all he was the man who symbolised the spirit of the independence struggle. Pakistani documents of the time mention that there were two dangerous men in the country: Moulana Bhashani and Sheikh Mujib -- and all seditious souls went to them. Left behind by history

pro-Soviet and pro-Peking factions. Interestingly, around that time, the leaders from East Pakistan Communist Party also submitted two theses on the state of Pakistan. Khoka Roy basically said what he had repeated to Mujib while Md. Toaha argued for a national liberation struggle. In fact, Toaha had as early a 1950 written a veiled essay along the implementation of the Lahore Resolution where the intentions were not kept a secret. The pro-Peking lot was very anti-Mujib, partly because of his role at Kagmari, which suggested to them that he was pro-western, and partly because he had taken the nationalist struggle under his control away from the Left. In the odd contest between the "national" and the "social," the socialists were getting bashed. The man they had held in contempt for long was becoming or had already become the national leader. While in their secret meetings they openly took resolutions for independence, they also took a few against Mujib. In reality, the man had run past their history and left them with few options except to lambaste him and lament the cruel turns of history. By 1966, after the 6-points autonomy political formula of Awami League was presented, nothing was left on the screen except the political imagination of Sheikh Muib and his followers. There were critiques of this formula such as that of Comrade Abul Bashar, arguing that it would hurt the best interest of the poor and the people, but the course was set. Though some leftists even joined hands with the Pakistani intelligence to thwart the 6-point movement, nothing worked. The march to the final historical encounter had begun. A side-note on the leftists that is ironical is the rise of the Left cell under Sirajul Alam Khan, the permanent myth- and mess-maker of Bangladesh politics, inside the Awami League. At present a supporter of the government in power, by 1960 he had formed a Marxist-laced pro-independence cell secretly within the Awami League. It grew and swelled in strength, and the largest group of organised leftists was actually inside the party the communist orthodoxy hated most. They were clandestine, but also linked to the party, and were an effective foil to the right wing sympathies of Sheikh Mujib and his nephew Sheikh Moni. That must have been a strange fact for Mujib to behold, because, having broken the party in 1957 on the grounds of an attempt to purge the party of the Left, its power had never risen so high in the party as it did under Khan's leadership. Its later impact and journey is another story. Birth of the superhero Based on written and oral testimonies, we find that the old Inner Group of Moazzem Chowdhury was also connected, albeit indirectly, to the case. It appears that there were two groups of members, and in the slightly later stages a number of new members or associates are noted that included civil servants like Ahmed Fazlur Rahman and others who were also involved directly with the later Agartala case. The main initiative, however, came from a bunch of mid-level officers of the armed forces led by Lt. Com. Moazzem Hossain of the navy and several other members of the armed forces including Sgt. Zahurul Haq. Records show that there were a couple of meetings with Sheikh Mujib but his involvement wasn't there as a "conspirator." The Pakistan authorities first charged the officers involved and then added Mujib's name as the principle accused in 1968. From a trial of a conspiracy, it became a trial of Bengali nationalism, making it part of the list of serial decisions of the Pakistan army which sharpened the movement against Pakistan in its erstwhile eastern wing. Agartala baptised Sheikh Mujib as the uncontested leader, as Moulana Bhashani joined ranks, and the newly produced graduates of the universities, a result of Gen. Ayub Khan's rural developed policy, fought Pakistan down to the floor of the streets and lanes and then kicked Ayub Khan so hard that the conspiracy case was thrown away, the court was torched, and the judges escaped by a side door in a display of public rage against Pakistan and affirmation of a new identity that had reached its full term. It also preserved Bengalis from asking the question as to whether this trial was a sign of Mujib's loyalty to Pakistan or leadership of Bengali nationalism. Either way, the attempt to trash Mujib back-fired and he emerged from it as the supreme leader. Sheikh Mujib had written a defense which was widely distributed and read as a defense of the people and not a person. It mirrored the feelings of the people, and so, when he won the elections in 1970 in a manner so overwhelming that it left little negotiating space to anyone, it was not only appropriate but also prophetic. He was, to use a hyperbole, the uncrowned king of East Pakistan, and maybe not really uncrowned. It was his finest hour, everyone's finest hour, and lasted all of three months until bullets cracked the March sky of 1971. Prisoner of history? These are not the words of an undecided man. He knew directly from a loyal Bengali stallion in the Pakistani stable, Air Vice Marshall A. K. Khandaker, what the Pakistan army was planning. He also must have known that he couldn't have his way with the 6-points beyond a point and that meant stepping back, but, given the situation that was all around, given the locked in verdict of the votes, of overwhelming public pressure, the pressure from Sirajul Alam Khan's militant cadres, his freedom was limited too, and he had become part of a huge procession pushed by its own momentum. Was he a prisoner of his own history that he had helped to create? I have asked leaders of the party on these matters and never got any proper answer. Most of them said that they had never expected a confrontation of the scale of 1971. Even the Pakistan army didn't, and had hoped to end the matter in a few days, and sit down to a civilised dinner. Or did Mujib know that a bloodbath was inevitable and taken the chance and made the choice?. People would have given all for him, he knew, and maybe he did take a chance.

An enduring myth about Sheikh Mujib was that he was not very smart -- the stubborn, large-hearted fool as Moazzem Chowdhury and many others thought. Yet I find that Mujib may have been one of the most secretive politicians we have ever come across and probably let people think what they wanted about him because it suited him. Another myth is that he was Suhrawardy's man, and, in fact, much of his political reputation is built on that. However, I shall cite a few examples to contest these two myths, as I myself stumbled upon them and had to reassess the man. Almost no independence movement was planned without Mujib in the middle, but except for the ill-fated trip to India, he was never an activist in any one of them. This is remarkable considering that he was the natural leader of them all. More interestingly, he never refused to listen to any of the plans, and, one supposes, offered encouragement. It was as if Mujib was part of all of them, but again not involved in any of them. Both Ahmed Fazlur Rahman and Moazzem Chowdhury told me that they had contacted Indian intelligence -- several London-based ex-pat Bangladeshi politicians have said so too -- from his it part of the list of serial decisions of the Pakistan army which sharpened London hotel, but even in the same hotel, when both were present, neither knew that Mujib was talking. It seems to me that this sort of thing helped Mujib to give the impression of being manipulated and yet in the end be his own man. There was never an instance when Mujib was forced to go along. The other bit is about his loyalty to Suhrawardy. That Suhrawardy was a passionate Pakistani is not contested, and Mujib had gone along, but after Kagmari or the martial law imposition, this becomes a clearly contested assertion. Suhrawardy never gave up on Pakistan, but Mujib was meeting Khoka Roy, a rabid enemy of his mentor and their patron, the US, to discuss independence, without any sharing of thoughts with his chief. And once turned down, he was on his way to Sylhet to talk to India without informing anyone. Suhrawardy's man would hardly have broken up Pakistan. After Suhrawardy's death, he focused entirely on the politics of East Pakistan, and the Pakistan Awami League became a signboard existence only. He was not interested in Pakistan, and that may explain why he was also reluctant to make any sacrifices for the Pakistan he was not too keen about in 1971. There was a lot of mutual hostility at that time, if anyone cares to remember. In the end, he was doing what he did best. Leading a people, though some questions will stick around about the cost-benefit analysis of independent Bangladesh and the blood-letting and suffering that people endured. In all fairness, one must remember that the decision to strike by the Pakistan army was sealed and ready, long before even the parliament convening drama by Gen. Yahya Khan began. Did Mujib go along with inevitability?

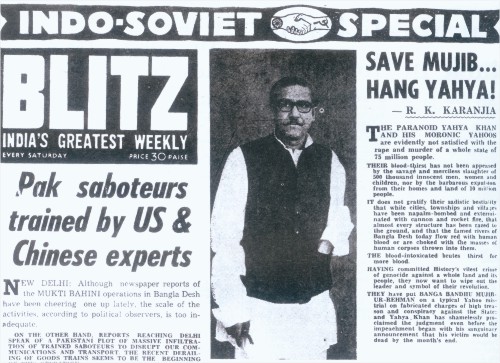

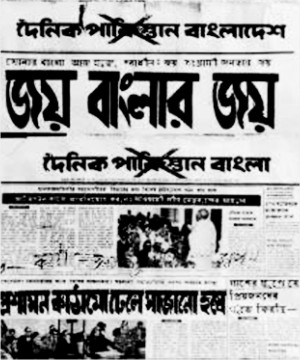

The second history of Sheikh Mujib begins Ziaur Rahman is not just a contestant against Sheikh Mujib for a place in history, but for that unique place which is reserved for supreme leaders. This applies not just to the management of the state in the post-1971 era, but even as the trigger-man of the independence war. So high is the contest, and so defensive the state of the supporters of Sheikh Mujib, that much time is spent on the most useless debate of them all: who was the declarer of independence, whatever that may mean. It has assumed as great a significance as the identity of the person who led the independence movement to its end goal. It is not a debate at all, but an indication that no one, including Sheikh Mujib, is free from the accusing fingers of history for having failed to live up to the image that history had created for him. When Sheikh Mujib refused to hide or lead the war from elsewhere, he probably knew what he was doing. His arrest and subsequent trial as it progressed became the rallying call for activists all over the world. The US State Department archives mention the efforts of the US officials and diplomats to convince Yahya Khan not to take any drastic step such as execution. It does seem that Yahya was giving that assurance, but he was hardly his own man. Throughout that period there was not a moment that didn't belong to Mujib, and Mujib in Lyallpur jail, waiting to be hanged, as he thought, and his conduct during the trial, and everything else, made him the symbol of Bangladesh in defiant chains. It was when he wasn't there that he was the ultimate supreme leader. Sheikh Mujib's Mujibnagar problem? Tajuddin also had to contend with the Indian plans that raised the Mujib Bahini led by Sheikh Moni and Sirajul Alam Khan jointly as a counter-force of sorts to the Mujibnagar forces (or a fighting force that would be run by India). It was under Indian command, rule, and wish, and a less calm man than Tajuddin would have erupted in anger, and indiscretion may have followed, but he was a model of extreme grace under pressure. It was this kind of maturity that gained the respect of the Indian war machine, especially its civilian members, who saw him as essential to the task of making Bangladesh independent (or to their objective, which was to split Pakistan). Tajuddin's one loyal group were many of the bureaucrats of the Mujibnagar government, some of them ex-leftists, who saw him as a bearer of the red flag of bureaucratised socialism made popular by Russia and China. This was also echoed in the Indian bureaucracy, full of old Oxbridge Marxists like P.N. Haksar and D. Dhar, Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi's two top deputies.

The following statement may be contested but many Mujibnagar insiders have told me that Sheikh Mujib didn't enjoy the sudden rise of Tajuddin. "He in fact didn't like to hear much about what happened in Mujibnagar, and that was an episode he didn't want to know too much. Once at a party meeting, when Tajuddin insisted that Bangabandhu hear about what went on in 1971, he listened for a while and then started to pretend he had fallen asleep," one of those present once told me. By March 1972, came the announcement that Sheikh Mujib had sent the declaration of independence to many places before arrest and Zahur Hossain Chowdhury, AL supremo of Chittagong, had read it out to all. This was rather unexpected because nobody really cared if there was such a declaration or not. Mujib was insisting when no one was asking. The departure of Tajuddin from the cabinet and the downsizing of many of his followers coincided with the star of Sheikh Moni (who had tried to have the broadcast of Tajuddin Ahmed's first speech after the formation of the Mujibnagar government on April 17, 1971 blocked, but failed) rising dramatically. Over time he was effectively becoming the deputy of Sheikh Mujib, and, with Sirajul Alam Khan out of Awami League with his own party, there was nothing to stop Bangladesh turning into Mujib's somewhat private concern. Mujib's Bangladesh history is not remembered with joy, though certainly laden with arguments. He ran an administration that was unable to cope with post-war rehabilitation and yet all the trappings of post-war criminality like hoarding, black marketing, permit selling, etc was on. Prices went out of control and the 1973 elections were so heavily rigged that they gave Mujib, the symbolic democrat, a sad name. A study of failure, frustration or inability ? A few became rich dramatically, and most didn't, which made the matter worse, and when by 1974 Mujib imposed emergency rule, soon to be followed by one-party rule, the situation was deplorable. Rarely had one man who had reached so high come down so low. What the rogue group of soldiers did on August 15, 1975 was more a physical elimination of the person. But the Mujib of the first history had not been in evidence since soon after he returned from Pakistan in early 1972. The Mujib that Zia contested after Mujib's death was a man without much history, and, that too, the history of a failed administrator. It is by linking the two Mujibs that our confusions start about his role, worth, and failings. It is about Mujib and his multiplicity. 1971 was a break between one Mujib and another, something mostly ignored. That is how the memories get mixed and also live on, causing friction without any historical basis. The puzzling autocrat Is this something his history contributed to? Mujib was a product of a historical continuity that began long ago in pre-1947 India, where the party he belonged to, the Muslim League of India, had no internal democracy either. The records of the 1946 elections of India which more or less delivered Pakistan (and are also called the Pakistan referendum elections) show the intense internal conflict with Jinnah's autocracy. Prof. Harun Rashid, who has covered much of that phase in his book The Foreshadowing of Bangladesh, has shown the imposing nature of central leadership that made party practices very undemocratic. This culture was transmitted through the Bengali version of the same party, namely in the Awami Muslim League, after 1947. Subsequently, when the party broke up into NAP and AL, the Bhashani version had to physically fend off attacks when they tried to hold their first Congress in Dhaka when AL thugs attacked the meeting. The point is simple. Where did Mujib ever come across internal political party democracy that he would learn from, let alone practice? Mujib came from a tradition of non-democracy, and other parties in the political zone, including the Left parties, were never democratic, either. To ask Mujib to be democratic when no one else was is unfair. It is just that after 1971, the same tendencies became public, and, since the party was in power, the effects were felt by and visible to the people. Hence the puzzle about his undemocratic behaviour despite his alleged democratic roots. Evidence would point to a man who thought the objective was more important than the process -- and this was the dominant political tradition in Bengal. Since no party other than the descendants of the mother party -- Bengal Muslim League -- came to power, the political culture never changed. The current situation, where both AL and BNP are resisting attempts to introduce reforms relating to internal democracy, is a good example of how deep the Undemocratic roots are. The activities of the present government to facilitate political change in parties while being in the administration is also part of the Pakistan tradition, where bureaucrats have always thought that politics should be managed from the Government House. They display the power of traditions.

Are nationalists ever democrats? In fact, nationalism is, almost by definition, of insignificant democratic content. Nobody will deny that the various groups fighting all over the world have strong nationalist content, but most are not only chauvinist, some are fascist too. That is the nature of nationalism. What made Mujib significant was also what made him so ruthless. The Left of the many shades, except the old pro-Soviet guard, has often complained that Sheikh Mujib was violently repressive of the leftists. This argument is the least understood of the lot, because Mujib never showed any love for the Left in his entire political life. For a period of time, there was a possibility of convenience, such as his overtures to the Communist Party on organising a joint movement for independence, but that fell through. The closest proximity came when BKSAL was formed, and, while this, to the Soviet followers, was a gain, it seems to Mujib that it was a convenient gathering of more supporters, who, given the framework of politics at that time, ensured Indian and Soviet support. One may cite the constitution passed under Mujib as a sign of his commitment, but both the Fourth Amendment and the Special Power Act would prove how fragile this commitment was. The Indo-Soviet influence was a major issue here and the Indian government certainly didn't hesitate to throw its weight around when it wanted. This wasn't just during the war period when relations often seriously dipped. India fought its own war, and so did Bangladesh, and there were points of convergence, but it wasn't the same war. As the host country to the Bangladesh war effort, it pushed through many decisions, the acme being the formation of the Mujib Bahini, but it didn't fight the Bangladesh war on behalf of the Bangladeshi people. In my interview of Mujibnagar officials, many spoke of their determination to take charge of key installations like the Chittagong port, the airport, etc before Indians did as soon as the war was done. This is not hostility, but the spirit of a newly independent people who didn't see this as a joint war, but a war of their own which India had supported. Indians were not very sensitive to this point, or were more absorbed in their own war. Those old enough to remember December 1971 will recall that a number of Indian officers were announced to take charge of various ministries and departments, including the police, but this was a very unpopular decision that the Indian government withdrew soon. Indians are nationalists, too.

The Fourth Amendment and fragile loyalties Indira Gandhi was a socialist and a secularist of the old-fashioned variety, something akin to Tajuddin Ahmed, who played a prominent role in constitution framing. So the Hindus of Bangladesh were given some reassurance through the constitution, as well as from the fact that India stood as their friend next door, which in the end didn't help much. Records show that AL leaders were leading property grabbers of Hindus after 1971. The constitution never protected them, though it won their undying loyalty. So Mujib didn't turn socialist overnight. Very little in the management system changed and "nationalisation" of industries owned by Pakistanis was equated with socialism, which became synonymous with looting unaccountable state owned enterprises. Mujib and the military Mujib's response to the call of sharing state power was a standard response of exclusionary politics, where all political truth lay with the party that led the war. This is a typical response, which the Muslim League also showed after 1947, when opposing the party in power was considered opposition to Pakistan. Mujib did what any chauvinist would have done. Everyone outside the party became the enemy, and he acted accordingly. The state and the party was one. To this must be added Mujib's systematic weakening of state institutions while the one institution that bothered him -- the army -- grew in strength. Gen. Jagjit Singh Aurora, the man who received the surrender of the Pakistan forces at Dhaka, told me at his Delhi residence that Mujib should not have "messed with the army." He paid a steep price for doing so. Where was the messing, I asked. Well, he set up a bahini, didn't he? I have heard this complaint from the few army officers I have talked to about the topic. The Rakhi Bahini didn't just repress the people, but also acted as a guard against the army as a takeover agent. Sadly, it did not succeed, but the man who had built the Mujib Bahini for Indira and the Rakhi Bahini for Sheikh Mujib, General Oban, created a tradition of repression that lives with us today. The Indian Maoists are also fighting the state, but did they go and join hands with the state intelligence agencies, as our venerable leaders of the Left did to bring Mujib down? Maybe the warnings of a Mujib in power may have been partly true, but the practice in East Pakistan and Bangladesh doesn't resemble what has happened in India. It seems much closer to what is on in Pakistan. Pakistan's shadow and the rest Although the two wings almost immediately began journeys towards their own imaginations of their statehood, both showed similarities in the system of managing the administration, politics, society, dissent, rule of law or its absence, role of intelligence agencies in civilian affairs, use of bribes to manipulate politics and the rest of public life, executive control over the judiciary, wealth making as a form of reward for supporting the state, elevated position of the executive as a cadre of non-accountable servants of the state, and independent status and growth of the army as an institution to act as guarantor of the state, especially in the absence of or not establishing by choice a system of regular constitutional politics. This is still what Pakistan is, and over the years this phenomenon has grown, while a reading of Bangladesh would not show any major deviation from this paradigm either. The Bangladesh state has absorbed the socio-political culture of Pakistan which was produced by the supremacy of the elite class and their non-accountability. Pakistan has influenced our ideas regarding the nature of the state rather than retail ideas of which songs we sing on the street to classify our entertainment culture. The cultural traits that we share with Pakistan refer more to the response mechanism of the state. The idea of BKSAL was embraced but the electoral process or constitutional democracy wasn't, making the case that the lessons learnt of managing the state were easily applied. The inordinate strength and resilience of the military and the bureaucracy is a much neglected study area, because although they practically didn't exist throughout 1971 as institutions, they almost immediately reverted to their own established pattern immediately after 1971 was over. It is the continuity of the state that was offered by them and the state greedily took it and that is why it was inevitable that they emerged stronger with every month till the army even challenged one-party rule and then fought various factions of each other till the mainstream military rule was established. It was repeated in various forms under Ershad and in a non-conventional refrain later, but the military as the stabiliser of the last resort where political culture of the civilian leadership Going by the past history of nearly 40 years, our political history and economic management ideals are certainly closer to Pakistan, and today the similarity is not less either. Is it that Sheikh Mujib learnt the methods of ruling from the government he once served as well? The missing Suhrawardy factor or Jinnah's revenge ? There is not one Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, and to describe him as one person across the decades, states, and histories would be meaningless for both his admirers and detractors. He had clearly demarcated histories, and in each he played specific roles. If he had learned from and about Subhash Bose and Suhrawardy, he also learnt from Liaquat Ali Khan, going by the evidence that we observe. Incidentally, the first prime minister of Pakistan and the first prime minister of Bangladesh were both assassinated. In the end, history overwhelmed him. He was only doing what he knew how to do. Gandhi must have known in his heart what was beyond him, which was to administer India, and in the end left an increasingly democratic though a very flawed India behind as his legacy. Jinnah seemed to have left behind one full and one nearly full state as his inheritance, both overrun by the same ailments. Or was it his revenge on the Bengalis he never liked? Afsan Chowdhury is an eminent writer and columnist. |

By 1961, he made contact with the Indian High Commission for Mujib to cross over to India. Several first-hand contacts say it happened in early 1962.

By 1961, he made contact with the Indian High Commission for Mujib to cross over to India. Several first-hand contacts say it happened in early 1962.  Star

Star

Political repression was high and the Rakhi Bahini was created, some said to protect Mujib from a restive military and to have a force under his direct command. It behaved much like the RAB of today, picking up and disappearing people, which made it the most feared symbol of state and its unaccountable power.

Political repression was high and the Rakhi Bahini was created, some said to protect Mujib from a restive military and to have a force under his direct command. It behaved much like the RAB of today, picking up and disappearing people, which made it the most feared symbol of state and its unaccountable power.

remains underdeveloped, undemocratic, and ultimately unable to produce mature state management cadres from the political womb, is more a Pakistan model than from anywhere else.

remains underdeveloped, undemocratic, and ultimately unable to produce mature state management cadres from the political womb, is more a Pakistan model than from anywhere else.