Farmers giving up black tiger shrimp cultivation amid losses

Noni Gopal Baidya, a resident of Sutarkhali union in Dacope, a southwestern coastal upazila under Khulna division, began farming exportable black tiger shrimp on his 6-7 bighas of land in 1991.

Encouraged by the high profits in a short time, he later leased an additional 15 bighas from neighbouring farmers to expand black tiger shrimp farming, locally known as Bagda, once dubbed as "white gold".

At that time, he and others in his locality farmed black tiger shrimp under shared arrangements. People became shareholders in shrimp farms based on their investment capacity.

Baidya, too, was part of such a collective farming venture.

A few years later, he partnered with seven or eight local farmers and leased 200 bighas of land in a neighbouring union, Banisantha, for shrimp farming. However, due to continuous financial losses and growing campaigns against shrimp farming by locals and NGOs for holding saline water on farmlands, they abandoned the farm within six years and returned to their native areas.

By 2008, Baidya had completely stopped black tiger shrimp farming and never resumed it.

In Baidya's locality, nearly 800 families were once involved in shrimp farming. Today, almost no one in his area, which once had 20,000 acres of land under shrimp cultivation, is in the trade. The people of the union have completely abandoned brackish water shrimp farming.

"Due to continuous losses from high mortality and low prices compared to costs, we had to give up the farm," said Baidya.

"Shrimp farming is such a business that even if you suffer losses for two years, you might break even in the third year. If you're lucky, you might make a profit in the fourth year. But suddenly, without warning, you might lose everything. That uncertainty made me leave shrimp farming and return to traditional agriculture," he said.

This is not an isolated case. Overall, black tiger shrimp farming, once the key item in a $550 million export industry, has been steadily declining.

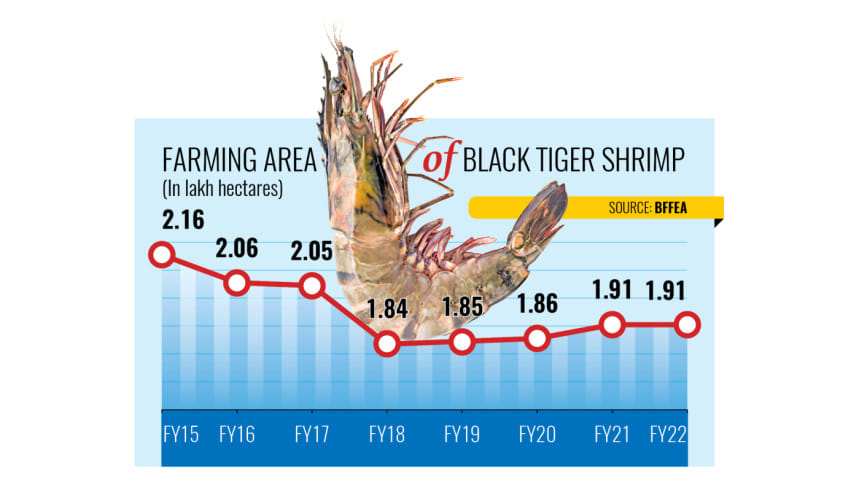

For example, black tiger shrimp was cultivated on over 216,470 hectares in the fiscal year (FY) 2014-15. However, the farming area of brackish water shrimp fell to 191,000 hectares, marking a 12 percent decline in eight years.

Production also dropped -- from 75,270 tonnes in FY15 to 70,220 tonnes in FY22, according to the Bangladesh Frozen Foods Exporters Association (BFFEA).

This decline has affected shrimp processing plants that mushroomed on the banks of Rupsha river in Khulna to capitalise on shrimp exports to the West in the 1980s and 1990s.

More than half of the 109 registered plants have shut down for numerous reasons, including less-than-required shrimp supply and falling demand for black tiger shrimp in the international market.

Buyers in the West have found cheaper alternatives to black tiger shrimp -- whiteleg shrimp or vannamei.

In Khulna, only 30 processing plants are now operational. In Chattogram, the number of functioning factories is 18.

The BFFEA said the combined capacity of the factories is around 4 lakh tonnes per year, but they receive only 7 percent of their required shrimp input.

Baidya once thought he had made a mistake quitting shrimp farming.

"But now, I feel I made the right decision."

He said that because of the indiscriminate use and holding of saline water on land for black tiger shrimp farming, paddy production had fallen as low as 6–7 maunds per acre. Vegetation was lost. Now, they produce 20-25 maunds per acre. Trees have returned, and they are growing watermelons.

"Now, some in my locality are cultivating freshwater shrimp," he said.

Like Baidya, around 30,000 farmers have gradually quit brackish water shrimp farming in Dacope upazila under Khulna district alone. The situation is similar in other places such as Satkhira and Bagerhat in the southwestern region, where shrimp farming was once the main source of income, thanks to exports.

"The biggest problem was disease outbreaks," said Abdul Malek, a 55-year-old farmer from Kharnia in Dumuria, Khulna.

He started black tiger shrimp farming in 1998 on 50 acres of leased land. At that time, shrimp farming was highly profitable. Malek is now struggling with losses and trying to quit.

He incurred a loss of Tk 7 lakh five years ago due to disease outbreaks in his enclosures and cyclones.

Farmers said recurrent cyclones such as Aila, Amphan, and Yaas over the past one and a half decades washed away their investments. The natural disasters also resulted in waterlogging, preventing farmers from practising agriculture.

Malek also blamed the government's restrictions on the intrusion of saline water into the polder area for his losses.

"Last year, I barely cultivated six bighas of land. I switched to paddy and watermelon farming,'' he said, urging the government to provide insurance schemes and ensure the supply of pathogen-free shrimp larvae to revive the export-oriented industry.

"Otherwise, shrimp farming in Bangladesh will keep shrinking."

Masum Ali Fakir, chairman of Sutarkhali union, said many farms remained underwater for nearly three years after Cyclone Aila in 2009.

"Since then, shrimp farming has never recovered in our area," he added.

Bagerhat Shrimp Farm Owners' Association President Sakir Mohitul Islam said that the district still has 35,000-40,000 shrimp farms, involving over 1 lakh farmers. However, many are losing interest due to multiple challenges.

"There is a shortage of quality shrimp larvae. There is also opposition from local environmental activists. As a result, farmers are gradually stepping away," he said.

"The fisheries department is mainly focusing on semi-intensive farms and providing various incentives for them. But traditional shrimp farmers receive almost no support."

Islam said shrimp farmers suffered three major losses last year.

First, in February, there was high mortality in the farms due to a disease outbreak in the larvae. Then, Cyclone Remal caused further destruction.

"Yet, farmers received no assistance from the government."

Shyamal Das, director of the BFFEA and managing director of MUC Foods Ltd, said rising temperatures, fluctuating salinity levels, shallower shrimp ponds, and a lack of high-quality larvae are discouraging farmers from continuing shrimp cultivation.

Md Jahangir Alam, deputy director of the Department of Fisheries in Khulna, said farmers in many areas are growing rice on land where shrimp was previously farmed.

"Besides, in many areas, farmers are no longer allowed to pump saline water into their enclosures. In some places, they are actively prevented from doing so. Moreover, climate change is also negatively affecting shrimp production. Rising temperatures cause enclosure water to dry up, and shallow water levels make shrimp farming increasingly difficult. As a result, frustrated farmers are shifting to alternative livelihoods," he said.

Farmers who have long depended on shrimp for their livelihoods are struggling.

"They can no longer use their land for shrimp farming. At the same time, rice cultivation in those areas has not been profitable enough. If there is land zoning -- specific areas designated for shrimp farming and rice cultivation -- conflicts over land and water use can be avoided," added Alam.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments