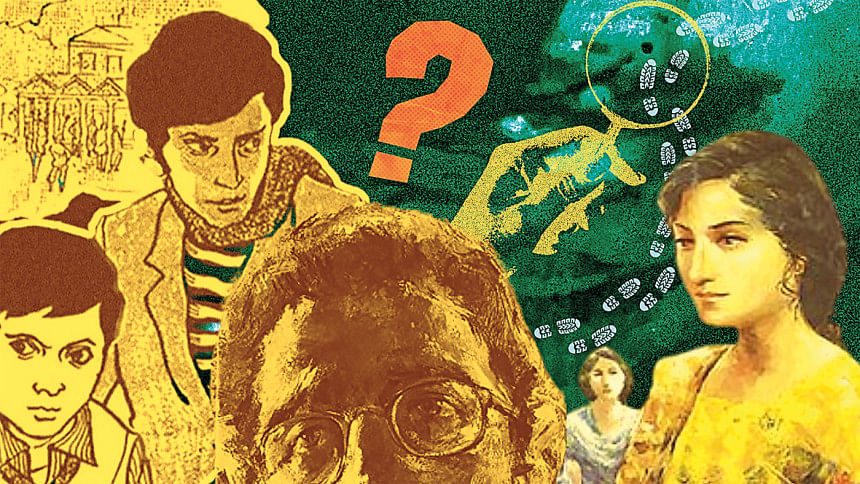

Feluda, the idea of ‘Bangali Bhadralok’, and the gendered silence in detective fiction

There's a certain warmth and ache that comes with remembering how we first met the worlds of Feluda, Sherlock Holmes, or Harry Potter; stories that quietly slipped into our lives, often as prizes at school sports days or stumbled upon in the quiet corners of an elder sibling's shelf. Feluda came to us gently. Wrapped in brown paper, or worn from many reads—and once found, he stayed. There was Topshe, too. The cousin, the chronicler, the quiet witness to brilliance. We didn't just admire him; many of us longed to be him. To be that trusted companion, that chosen one who gets to walk beside someone who could deduce a man's secrets from the way he stirred his tea. To board a train to Jaisalmer or trail through ancient ruins in Lucknow, to chase riddles that turned ordinary days into adventures. In our own way, we all wanted to crack a code, spot a clue, chase the thrill of something larger than life. But as we grew older, the lens shifted. The nostalgia remained, but so did the questions. Slowly, quietly, we began to read the silences too—the gaps, the absences, the shadows.

Detective fiction, by its very nature, has always been a well-tailored, pipe-smoking boys' club. When the average reader imagines a sleuth, the mind's eye conjures up a man; sharp, cerebral, and sartorially sound.Be it Sherlock Holmes, Byomkesh Bakshi, or Satyajit Ray's iconic Feluda. The genre's gendered legacy is hard to miss: Even as Agatha Christie's Miss Marple or Suchitra Bhattacharya's Mitin Mashi made their marks, they remained mostly outliers in a landscape dominated by men draped in trench coats and deductive prowess. The Bangali literary world, in particular, has long reserved its detective pedestal for the likes of Feluda, Kakababu, Kiriti Roy, or Byomkesh, while early female detectives like Krishna (penned by Prabhabati Devi Saraswati) never quite cracked the mainstream.

It is against this backdrop that the absence of women in Feluda's world becomes not just a narrative quirk but a telling reflection of the cultural and social codes of the Bangali bhadralok. Feluda-Pradosh C. Mitter arrived on the scene in 1965, and over the course of 35 published stories (with four unpublished), he became the very embodiment of the educated, urbane, morally upright Bangali gentleman. His world is scrupulously constructed: We know about his father, his uncles, and the paternal lineages of both Feluda and his cousin Topshe, the narrator. Yet, when it comes to the women in their lives, the silence is deafening. The only mention of Feluda's mother is a single line: He lost her at the age of nine. Topshe's mother, too, is a ghostly absence—no emotional shading, no narrative presence, not even a passing comment.

This is not a matter of oversight. As Ray's aunt, the celebrated author Leela Majumdar, wryly noted in her essay, "Felu Chand" (Sandesh, December 1995): "…There's something rather odd, you know, in Feluchand's stories and novels. Yes, why is it that we never see any family members or relatives of the detective and his assistant? Even the homes of the villains seem to have no one except servants!" The critique is as sharp as it is accurate. For a series that revels in the minutiae of Bangali life, the absence of mothers, aunts, and sisters is not just noticeable.It's apparent.

Of course, there are exceptions, but they are rare and fleeting. In "Gosainpur Sargaram" (Sandesh, Sharadiya 1383) and Jahangirer Swarnamudra (Sandesh, Sharadiya 1819), elderly women briefly influence the plot. "Chhinnamastar Abhishap" (Desh, Sharadiya 1385) introduces Neelima Devi, who aids Feluda's investigation, while in "Ambar Sen Antardhan Rahasya" (Anandamela, 1983), Mrs Sen and her daughter provide crucial clues. In "Shakuntalar Kanthahaar" and "D Munshir Diary", female characters are central to the mystery's resolution—Mrs Munshi's actions, for instance, are pivotal to the case. But these appearances are rare and lack continuity. These women; wives, daughters, or informants—may serve the story in isolated moments, but they are never part of the core world. They do not return, they are not remembered, and they are never central. What catches the reader's attention, over time, is not the total absence, but the absence of continuity. Yet, these women are supporting actors in a drama where the spotlight remains firmly on the male trio: Feluda, Topshe, and Lalmohan Ganguly (Jatayu). There is no recurring female character, no female foil or confidante. The adventures, camaraderie, and even the banter are resolutely male.

This narrative architecture is no accident. It is deeply tied to the ethos of the bhadralok, a term that has shaped the Bengali psyche for over two centuries. The bhadralok (literally "gentleman")—emerged in 19th century colonial Bengal as a social class defined by education, English proficiency, and a genteel, "civilised" lifestyle. They were the torchbearers of the so-called Bangali Renaissance, the intermediaries of the empire, and the self-appointed custodians of culture and taste. As Partha Chatterjee observes, the bhadralok identity was less about birth and more about acquiring a "language of respectability and a genteel lifestyle that is, as it were, nobody's patrimony, but one that each person has to acquire through learning in order to become bhadra".

But this respectability came at a cost. The bhadralok project was built on a strict division between the public and private spheres—a division that mapped neatly onto gender. Men were the rational actors, the seekers of truth, the explorers of the world; women, by contrast, were relegated to the home, the keepers of tradition and spirituality. Partha Chatterjee, in his seminal essay "The Nationalist Resolution of the Women's Question", explained that the "ghar" (home) and "bahir" (outside) dichotomy is at play here: "On the material level, the West served as a blueprint. But on the spiritual level, there occurred a classicisation of tradition…the West continued its dominance while on the level of problematic, in the sphere of specific cultural and social contexts, ancient records and texts were invoked in order to reform Hindu morality and sexuality that was deemed fit for the 19th century". In Feluda's meticulously ordered universe, this separation is absolute. The detective's world is one of logic, mobility, and public engagement—spaces from which women are conspicuously, and perhaps intentionally, excluded.

Ray himself was acutely aware of this absence and addressed it directly. In a note for a Feluda collection that was published in 1988, he wrote, "To write a whodunit while keeping in mind a young readership is not an easy task, because the stories have to be kept 'clean'. No illicit love, no crime of passion, and only a modicum of violence. I hope adult readers will bear this in mind when reading these stories." While Ray's candour is admirable, his rationale inadvertently exposes a deeper bhadralok anxiety: the notion that the mere presence of women threatens the narrative's "cleanliness" or innocence. But as literary history has shown through characters like Miss Marple or Mitin Mashi; female presence need not imply sexualisation or moral ambiguity. This unintentional suggestion, that female presence is somehow entangled with moral complexity, impurity, or adult content—speaks volumes about the norms of his time. Yet, this is precisely where Ray's brilliance could have defied convention. In a literary landscape where women were routinely sidelined in detective fiction, a writer as versatile and imaginative as Ray could have shaped a narrative that included strong, witty female characters without compromising the clarity or sophistication of his stories. Far from "unclean," such inclusion would have expanded the imaginative scope of his readers, especially young girls, and offered them a different kind of mirror. It would not only have reflected the intellect and agency of women but also widened the very idea of who belongs in a world of clues, codes, and conclusions.

This absence is not just a reflection of genre or audience. It is a window into the anxieties and aspirations of the bhadralok class—a class that defined itself by its intellectual and moral superiority, its disdain for the "chhotolok" (the uncultured masses), and its ability to keep the messy realities of sexuality and domesticity at bay. As Sayandeb Chowdhury notes, "Feluda's world is not just a boys' club; it is a carefully curated masculine enclave, insulated from the ambiguities and entanglements of female subjectivity." As Partha Chatterjee argues, the bhadralok identity hinges on a bifurcation of the "spiritual" (domestic, feminine) and "material" (public, masculine) spheres. Feluda's all-male universe, devoid of domesticity or female influence, becomes a literary manifestation of this divide—a detective who solves mysteries not just for justice, but to uphold the bhadralok's self-image as the enlightened guardian of Bangali modernity.

Interestingly, there is a noticeable dissonance between Ray's comments on limiting gender presence in the Feluda stories and his cinematic practice. Films like Charulata (1964), Devi (1960), and Mahanagar (1963) reflect his deep sensitivity toward women's inner lives and societal struggles. Even in his adaptations of Feluda for the screen, Ray introduced female characters absent from the original texts, like Dakshinaranjan's mother in Sonar Kella (1974) and the female bhajan singer in Joy Baba Felunath (1979), likely recognising the expectations of a broader, more adult audience. These decisions hint at an implicit belief that certain genres or readerships require the exclusion of certain genders, whether due to artistic limitations, market considerations, or adherence to established genre conventions. It reveals not just a narrative strategy, but a cultural positioning: a scepticism, perhaps, of the wider expectations of detective fiction at the time.

Written primarily for Sandesh, a children's magazine, Satyajit Ray tailored these stories to young readers, and naturally, the social norms of that era shaped much of what was included and what was left out. While today's readers may notice the silences or limited representations, it's essential to read these works with an understanding of their historical and cultural moment. Yet, given Ray's brilliance and sensitivity across his works, one might still wonder if the Feluda stories could have offered a slightly more inclusive imagination. That critique doesn't diminish the charm; it enriches it. In revisiting what's missing, we see not only how far we've come but how timeless stories can invite timeless questions. That such hopes exist is perhaps the greatest compliment to the legacy Satyajit Ray leaves behind.

Mahmuda Emdad is a women and gender studies major with an endless interest in feminist writings, historical fiction, and pretty much everything else, all while questioning the world in the process. Reach her at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments