China’s great green march across the globe

On the outskirts of the Indonesian city of Semarang in Central Java, a new factory is cranking out solar cells and assembling solar panels with the help of robots, while autonomous carts whizz around ferrying parts and components.

The Trina Mas Agra Indonesia solar panel plant, operational since October 2024, is a US$100 million joint venture between China's Trina Solar, Indonesian conglomerate Sinar Mas and Indonesian state utility PLN.

With an annual one gigawatt (GW) total panel capacity that is set to increase to 3GW, the plant is the first and largest integrated solar cell and solar panel manufacturer in Indonesia. It is helping to accelerate a much-needed energy transition in South-east Asia's largest economy, and could in future bring green electricity to Singapore.

In the past year, Chinese solar panel makers have been opening or ramping up manufacturing facilities in Indonesia to take advantage of a burgeoning domestic market with a low solar energy penetration rate and cheap local labour.

The fear of being targeted by tariffs remains real, even though the US is becoming an increasingly niche market for Chinese clean-technology goods after years of trade barriers first imposed by the Obama administration, then expanded by the Trump and Biden governments.

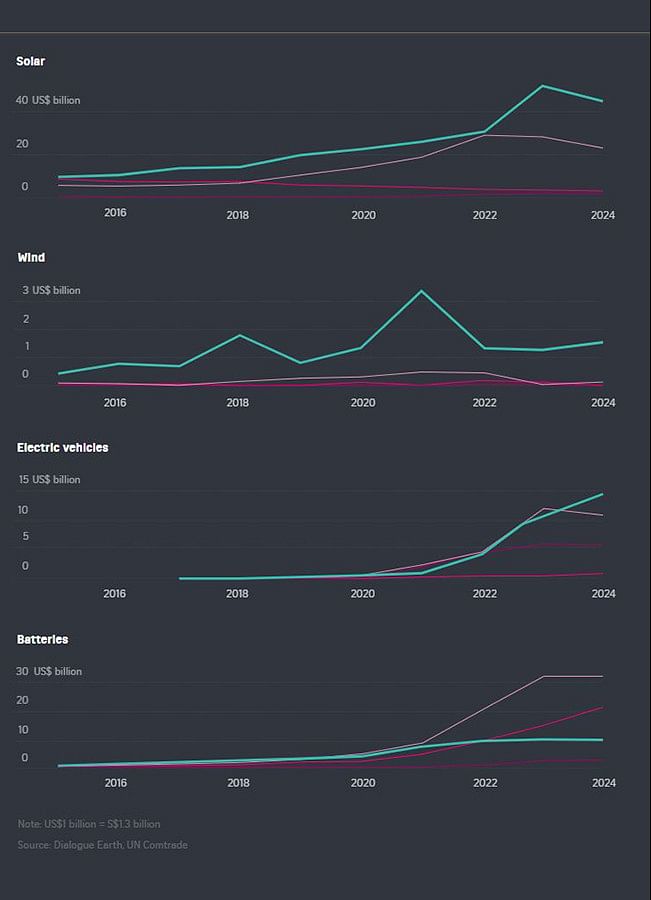

Only 4 per cent of China's total exports of solar power and wind power equipment and electric vehicles (EVs) go to the US, according to data from United Nations Comtrade. A decade ago, the US – and European Union – were key export markets.

The real focus now for Chinese companies is production overseas, including in the US and within the EU, but especially in developing countries where there is growing demand for clean-tech goods.

In Indonesia, there are now four Chinese solar manufacturing joint ventures, including Trina Mas Agra Indonesia, according to Mr Fabby Tumiwa, executive director of the Jakarta-based think-tank Institute for Essential Services Reform.

While Indonesia appears not to be in the US' cross hairs – for now – navigating America's trade policies is something of a cat-and-mouse game for Chinese companies, including in South-east Asia.

The US imposed a new round of anti-dumping duties on solar panel imports from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam in November 2024.

The punishing taxes of between 21.31 per cent and 271.2 per cent have already bitten some Chinese solar makers, who have exited Malaysia or scaled back their operations there.

"We are cautious," said Mr Wilson Kurniawan, a senior officer with Sinar Mas who has been closely involved in the Trina Mas Agra Indonesia solar plant.

"While Indonesia is not currently on the US solar trade blacklist, we are concerned about potential trade barriers, especially given America's increasingly protectionist stance."

The solar plant is focusing for now on the Indonesian market, where there is strong growth in the demand for solar energy, said Mr Kurniawan. Solar cells could in future be exported to other countries in the region.

Strong domestic growth is helped by falling solar costs and rising energy demand, as well as large-scale solar projects in Batam that may send renewable energy to Singapore in the coming years.

Behind China's shift to developing countries

In China, clean-tech companies squeezed by a hypercompetitive domestic market are saddled with excess capacity and razor-thin profit margins.

But in their pursuit of more lucrative markets overseas, they have unwittingly rubbed up against governments such as those of the US and EU countries, which are faced with the dilemma of protecting their own industries while ensuring national security and not over-relying on Chinese providers.

Given the rising barriers from developed countries, Chinese businesses are focused on the developing world, which is now the largest market for their solar, wind and EV exports, according to Comtrade data.

Chinese companies are finding these host countries, including Indonesia, happy to accept their know-how in clean tech – along with investments and factories that create local jobs and tax revenue – and the help in transitioning from fossil fuels.

"It's a win for the recipient countries, because they are getting factories, wind farms, solar farms, batteries and real jobs. A lot of them are getting research and development centres as well," said Mr Tim Buckley, director of Sydney-based think-tank Climate Energy Finance (CEF).

The Trina Mas plant, which is in Kendal Industrial Park, a joint venture between Singapore's Sembcorp and Indonesian developer Jababeka, employs about 350 people, 80 per cent of whom are Indonesian.

In the automotive hub of Karawang on the eastern outskirts of Jakarta, a US$1.2 billion factory – a joint venture between CATL, the world's largest EV battery maker, and Indonesia Battery Corporation (IBC) – is expected to start production in April 2026.

IBC is a government initiative that aims to turn Indonesia into a global EV battery manufacturer. It is owned by state-owned firms, including nickel and gold miner Aneka Tambang, oil and gas company Pertamina and electricity utility PLN.

It is one of a number of plants that CATL, which owns nearly 40 per cent of the global market share for EV batteries, has set up over the years, including in Germany, Spain and Hungary.

"The operation of these projects requires a large number of talented people in engineering, equipment, procurement, operations, research and development," said a CATL spokesman.

Holding the reins in a trillion-dollar clean-tech future

The Chinese have built an unassailable lead in the clean-tech space, despite the best efforts of US and EU leaders to apply the brakes. And the prize is immense.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) says the global market for clean technologies is set to rise from US$700 billion in 2023 to more than US$2 trillion by 2035.

The Trina solar joint venture project in Indonesia is just one of many projects involving Chinese clean-tech firms that CEF has been tracking globally. Since the start of 2023, more than 180 deals worth more than US$141 billion have been announced – and the number grows by the week. They include joint ventures and direct investments in energy projects.

The deals range from multibillion-dollar battery ventures in Europe and wind farms in Australia, Laos and Uzbekistan to EV plants in Turkey and Thailand. They also include solar panel manufacturing in Saudi Arabia and the US.

By spreading their manufacturing bases and deploying clean energy tech directly to power generation projects, Chinese firms can mitigate the risk of trade sanctions by the US, EU and other countries while entrenching China's dominance in clean tech.

Global trends such as energy transition and climate change also create international demand for clean-tech products and knowledge, which provide substantial business opportunities for Chinese clean-tech businesses.

China is also filling a gap left by the US' withdrawal from the global rules-based order and any kind of commitment to climate change, said Dr Sam Geall, chief executive of online environmental news site Dialogue Earth and an associate fellow at the think-tank Chatham House in London.

"For a lot of emerging markets, they're just starting in their development journey and building out energy infrastructure. If they can leapfrog towards renewable energy, if poor people getting energy access for the first time are able to go straight to renewables, it's fantastic," he told The Straits Times.

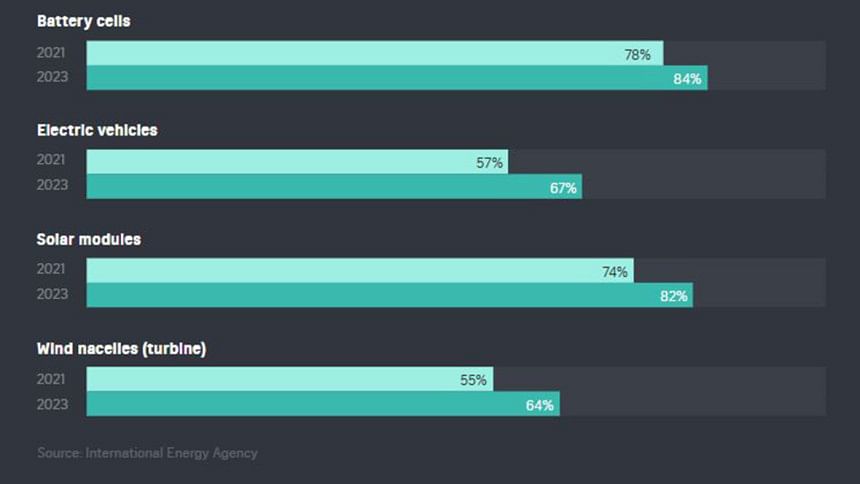

China's share of global clean-tech manufacturing capacity

How China became a clean-tech powerhouse

China simply has all the right ingredients: a well-established local supply chain, stable raw material prices and cheap labour. Its vast clean-tech industrial complexes at home have slashed the costs of green products globally, giving the nation a technological edge that foreign competitors are struggling to match.

"You can't manage the global energy transition without China," said climate analyst Li Shuo, director of China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute in Washington.

Scale is also China's secret weapon.

With a sizeable domestic market and state-backed financing, companies can produce at volumes others could not dream of.

Local governments in China sweeten the deal with tax breaks, free land and expedited permits, creating industrial ecosystems that draw talent and investment.

This level of state support is difficult for many other nations to match, triggering accusations from competitors of unfair trade practices and making China's exports an easy target for tariffs.

Diversified clean-tech supply chains can accelerate the global green transition because there would be fewer concerns over the supply chain and energy security, said Ms Belinda Schape, China policy analyst for the Helsinki-based Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (Crea).

"It could also lead to a faster uptake in clean energy in the manufacturing countries, with local production encouraging local deployment," she told ST.

The Global South has emerged as a major destination for Chinese clean-tech exports, vying with the EU, US and UK.

South-east Asia: A source of growth

South-east Asia is a major prize for Chinese clean-tech companies. With nearly 700 million people, it is one of the world's fastest-growing regions. And it needs lots of energy.

The IEA's 2024 South-east Asia Energy Outlook report said the region could account for 25 per cent of global energy demand growth between now and 2035, second only to India over the period. And regional electricity demand growth is set to grow about 4 per cent annually.

The problem is, the region remains deeply dependent on polluting fossil fuels and is struggling to ramp up clean energy investment, though more favourable policies in Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam are changing the picture.

But in Indonesia, South-east Asia's largest economy, the picture is less clear.

The new administration of President Prabowo Subianto has yet to fully clarify its energy policies, with mixed signals about support for renewable energy. Special climate change and energy envoy Hashim Djojohadikusumo on Jan 31 said he considered the Paris Agreement no longer relevant for the country, days after President Donald Trump announced the US' withdrawal from the UN climate pact for a second time.

Renewable energy investment in the region remains far below what is needed to match electricity demand growth or help the region meet its climate targets. Indonesia, for instance, had set a target of 23 per cent renewable energy by 2025 but later revised it to 17 per cent to 19 per cent.

The reality gap between the region's net-zero ambitions and true progress in its energy and green transition was highlighted in a 2024 report by global consultancy Bain & Company, Singapore's investment company Temasek, investment platform GenZero and Standard Chartered Bank.

An estimated US$1.5 trillion is required to fund the transition until 2030, but only US$45 billion has been invested across dedicated green investments since 2021, the report said.

Chinese companies are eyeing South-east Asia, which has already become a major base for solar panel and component manufacturing as well as a growing centre for EV manufacturing and battery materials production.

China Photovoltaic Industry Association data shows that by the end of 2023, nearly 20 Chinese solar companies had deployed upstream and downstream production capacity in South-east Asia through joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions and investments.

The region is also attracting Chinese investment to build wind and solar farms, including a soon-to-be completed 600-megawatt wind farm in Laos and high-voltage power line to supply the electricity to Vietnam.

Globally, suspicions remain in some countries about the true intention of Chinese green investment. These countries also fear that allowing local manufacturing may price out domestic clean-tech competitors, and they have labour concerns such as ensuring local employment and fair employment practices.

"China's domestic clean-tech industry maturity and growing overseas investment can provide a real opportunity for many countries in South-east Asia to meet rising energy demand and accelerate transition to a low-carbon economy," said Ms Caroline Wang, China climate and energy analyst at CEF.

But it is vital to cater to local development needs and respect local cultures and norms, she said.

In the past, some investments under China's Belt and Road Initiative were criticised for hiring only imported Chinese workers and accused of being debt traps for the host nation.

But the majority of clean-tech investment these days is by private Chinese companies, not state-owned enterprises.

And the companies have been eager to play up the benefits to the local economy and community. The Trina Mas Agra Indonesia solar plant has created new jobs and boosted demand for local products, Mr Wilson said.

In March 2025, Chinese EV maker Xpeng said it planned to begin local production in Indonesia, starting with its X9 and G6 models in the second half of the year.

China's EV giant BYD aims to complete its US$1 billion plant in West Java at the end of 2025, the head of its local unit said in January.

Over in Thailand, BYD's plant – its first passenger car production base overseas – has already created a large number of the more than 10,000 jobs it expects to generate. It continues to recruit and train local workers "to face the challenges of cross-cultural coordination and management".

BYD says it has also helped to attract more parts suppliers and promoted the upgrading of Thailand's new-energy automotive industry.

Headwinds for Chinese wind power players

While cheap Chinese clean tech has been embraced by developing countries that lack the expertise and have little concern over the politics of such transactions, it has created friction with other countries and regions.

The US as early as 2012 imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panels – tariffs that have expanded under subsequent administrations to cover other clean tech such as EVs, battery components and wind turbine parts.

The EU, which has tariffs on Chinese EVs, in November 2024 proposed that Chinese companies be required to transfer intellectual property to European businesses in exchange for access to EU subsidies under a new trade regime for clean technologies.

The latest tension is playing out in Scotland, where Mingyang Smart Energy – China's largest private wind turbine manufacturer and a world leader in floating offshore wind systems – is facing headwinds over its plans to set up a manufacturing plant.

Scotland, which aims to reach net-zero emissions of all greenhouse gases by 2045, has the biggest planned pipeline of floating wind farms globally, targeting 15GW by 2030.

About 60 per cent of Scotland's planned wind farms in the blustery North Sea, known collectively as ScotWind, are floating wind farms.

Even though the United Kingdom is no longer a part of the EU bloc, pressure on its government is mounting over Mingyang's role in the Scottish wind industry.

At the heart of concerns is the operational software embedded in the turbines which is made up of proprietary applications controlled by the manufacturer.

The UK's critical energy infrastructure would become vulnerable, argue detractors, as electricity generated by the turbines is connected to the power grid.

Observers say Scotland – and the UK – now risks sleepwalking into dependency on China to meet its ambitious climate target.

Mingyang had not responded to queries by ST as at press time.

In April 2024, the EU launched an investigation into subsidies received by Chinese wind turbine makers, alleging that these gave the companies an unfair advantage over their Western competitors.

Lawmakers have called for the UK government to make rigorous risk assessments before giving Chinese companies access to its energy network.

Chinese wind turbine manufacturers like Mingyang have faced significant cost pressures at home, where the price of onshore wind turbines has tumbled nearly 60 per cent since the beginning of 2020, according to data by BloombergNEF.

Even in overseas markets where they enjoy higher margins, Chinese onshore turbines were still nearly 30 per cent cheaper than those of US and European manufacturers between 2019 and 2024.

As Western competitors retreat from certain markets to focus on the US and Europe, where they can command higher prices, Chinese companies are moving in.

Goldwind, a major Chinese wind turbine manufacturer, took over a plant in Brazil in 2024 from GE Renewable Energy, giving it its first factory outside of China.

Those who have seen the most benefit from relatively cheap Chinese wind technology are developing countries, such as nations in Central Asia and Africa.

But in Europe, uncertainty over what kind of controls policymakers could impose on the Chinese companies is making it difficult for the manufacturers to navigate.

"It's a complicated space," said Mr Jaymes Sim, deputy CEO of Singapore company Mooreast, which is planning to set up its first overseas plant in Scotland to supply mooring systems for offshore wind turbines.

Chinese wind turbine makers have a significant track record at home, but overseas, they are coming up against three international players – Vestas, GE Vernova and Siemens Gamesa.

"I think there is a tension in how the Western world is going to defend the three players that are currently in the market. But the fact is these three players are also very full. So if you have a small project requiring, say, seven or 10 turbines, these three players are not interested in proposing something to you. If you can't go to them, and you can't go to China, then where do you go?" said Mr Sim.

Treading with caution in their green transition

Many countries that adopt Chinese clean tech or receive green financing recognise that they have to navigate the associated risks.

"Chinese overseas investments have in the past struggled with issues over transparency, consulting local communities and adverse environmental impacts," said Ms Schape.

Increased dependency on Chinese-controlled supply chains of such a scale and dominance could lead to economic and strategic vulnerabilities, especially during geopolitical tensions, said Ms Wang.

"To safeguard local solar module production, Brazil, South Africa and other countries have increased tariffs on imported Chinese photovoltaic products, while India has mandated the use of locally made solar cells in government clean energy projects from June 2026," she said.

For South-east Asia, there are pressures, too.

China's manufacturing scale provides a ready supply of products the region needs for the green transition, said Mr Dale Hardcastle, who leads Bain & Company's sustainability and decarbonisation business in South-east Asia.

But there has to be careful thought about how this impacts the region's existing industrial base. For instance, automotive manufacturing in Indonesia and Thailand is not well positioned to rapidly transition to EVs and compete with rising imports from China.

One needs to strike a balance between taking advantage of the rapid growth in low-cost solutions from China and managing the transition of local supply chains that deliver GDP and jobs for many economies.

Chinese companies also need to ensure their offshore investments comply with local environmental, labour and safety standards to minimise the risk of one-off examples being geopolitically weaponised against all Chinese overseas foreign direct investments, Ms Wang said.

But the opportunities and benefits to the local economy, industry and low-carbon development have a greater potential to outweigh the risks, she added.

Climate champion or power play?

China has positioned itself as the go-to supplier for a decarbonising world. Beyond capturing economic opportunities, what are its real motives?

At its core, its green revolution serves three goals: energy security, economic supremacy and geopolitical clout. By reducing its reliance on imported oil and gas – China is the world's second-largest oil consumer – renewables shield it from volatile markets and foreign pressure.

Economically, the sector fuels growth. In 2023, China had an estimated 7.4 million renewable energy jobs, or 46 per cent of the global total, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

Its clean-tech exports, projected to hit US$340 billion by 2035, rival the oil revenues of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates combined.

The clean-tech sector is a major contributor to China's economy, adding a record 13.6 trillion yuan (S$2.5 trillion) to its economy in 2024, or just above 10 per cent of the nation's gross domestic product. This could rise further in 2025, according to a recent report by Crea.

The nation is by far the largest investor in renewable energy. It added a record 356GW of wind and solar capacity in 2024.

That same year, China's combined solar and wind power capacity hit a new record of 1,407GW, surpassing its 2030 target of 1,200GW six years early. By contrast, the second-largest renewable energy producer, the US, trails with just over 370GW of total solar and onshore wind capacity.

Geopolitically, China's dominance amplifies its soft power. Through initiatives such as the Global Energy Interconnection, it aims to link grids worldwide, exporting surplus renewable energy and technology to allies and developing nations.

In South-east Asia, Africa and beyond, China pitches itself as a climate advocate, not a leader – a nuanced stance that sidesteps global obligations while expanding influence.

To do that, it needs to dominate the entire supply chain, which includes securing supplies of nickel in Indonesia and lithium in Australia, and buying mines in Africa. But there are also environmental concerns about deforestation and pollution associated with mining these materials, especially the quarrying and processing of nickel ore in Indonesia, which has angered environmental groups.

China also dominates the global processing of critical minerals. The nation primarily wants to be the "global businessman" for now, said Mr Li, the climate analyst.

And in this sense, what China is lagging behind in now is a political and diplomatic strategy to enable it to be that climate champion.

China has been under increasing pressure to contribute to climate finance as the largest greenhouse gas polluter and the second-largest economy in the world.

Greater investment in clean-tech manufacturing and renewable energy generation in poorer nations is one way China can boost its support. President Xi Jinping has personally pledged to promote the advancement of renewable energy in developing countries.

Ms Wang said that given China has a strong interest in ensuring the acceleration of the global energy transition, this could lead Beijing to take a more forward-leaning position in United Nations climate talks.

That could be a win for China and developing nations and could also potentially slow the pace of climate change, despite the best efforts of Mr Trump to derail global climate action.

Ultimately, China's great green march holds the promise of lower greenhouse gas emissions and cleaner energy globally and contributes to the fight against accelerating climate change.

For now, China's green juggernaut seems unstoppable, but the journey is not without its challenges – and how sustainable it proves remains to be seen.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments