How Sri Lanka’s booming economy ended in the worst crisis in its history

An unprecedented economic crisis is disrupting life across Sri Lanka. The government is running out of dollars to buy essentials. Mass protests are building against acute shortages of food and fuel. Multiple power plants are down, causing rolling power cuts disrupting life and production of key industries. Exams in schools are being suspended due to shortages of paper. Newspapers are either being forced to shut down, or cut their pages to stay afloat. Cooking gas shortages are forcing most bakeries and restaurants to close businesses. People even reportedly died while waiting in line for essentials.

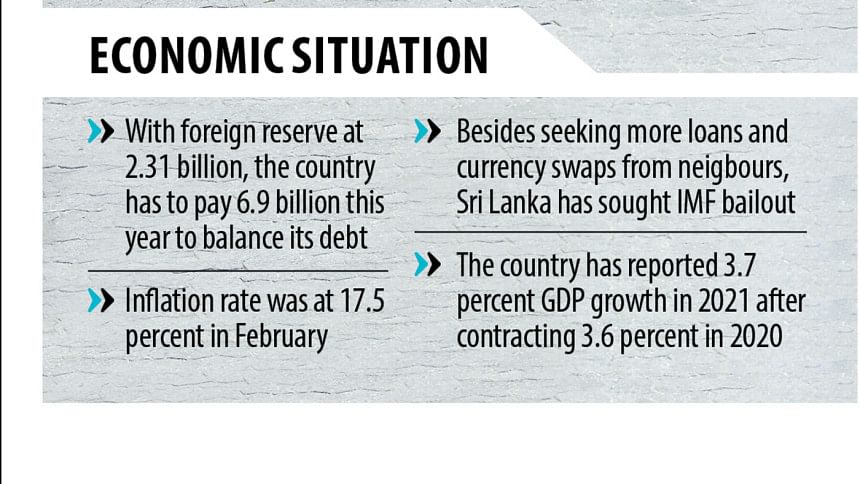

The government has closed embassies abroad. The central bank is printing rupees and hoarding dollars, sending inflation to a record high of 17.5 percent in February. The finance minister is begging neighbours for credit lines to buy fuel and essentials.

The situation is alarming to say the least.

The crisis in the country, which has been in economic emergency since 2021, this year reached an extent where President Gotabaya Rajapaksa called in the army to manage the crisis.

This is in complete contrast with projections made only a few years back. Despite a 30-year-old civil war that ended in 2009, the country was heading towards the status of an upper-middle-income nation. The tourism-based economy was thriving, bringing in more jobs and billions of dollars, and middle class comforts: high-end eateries and cafes, imported cars, and upscale malls.

But how did the situation in the country, outperforming its neighbours not so long ago, sink so low and so fast?

Experts blame the crisis on a number of economic missteps by successive governments and also on misfortunes. The country's enormous debt load, badly-timed tax cuts, the Covid-19 pandemic, which pummelled the tourism industry and foreign remittances, and, most recently, the war in Europe have wreaked havoc on the economy.

A 70 percent drop in foreign exchange reserves since January 2020 has left Sri Lanka struggling to pay for essential imports. The country is left with foreign reserves of only around $2.31 billion as of February, even as it faces debt payments of about $6.9 billion through the rest of the year.

In comparison, Bangladesh's foreign reserves, as of March 2022, stand at $44.2 billion, which has increased despite the pandemic.

Sri Lanka's foreign debt is at a staggering $51 billion.

After winning the election in 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksa made good on a campaign promise to slash taxes. The move, which included a near-halving of value added tax, blindsided some top central bank executives.

The case against the move was that reducing potential revenues when obligations were high was risky and it undermined a 2019 debt management plan that hinged on a narrowing fiscal deficit.

The economic argument for the cuts was simple -- to free up spending and boost Sri Lanka's ailing finances. A similar move in 2009 by an administration led by Gotabaya's elder brother Mahinda Rajapaksa had helped drive the country's economic recovery after the civil war.

That time the bet paid off as Sri Lankan economy grew around 12 percent in 2012. But this time, the country was unprepared for what came next.

Not long after the move, the pandemic struck, inflicting deadly blows to the two main sources of foreign revenue for the island nation – tourism and remittance. According to World Bank estimates, half a million out of 22 million people in Sri Lanka fell below the poverty line since the pandemic struck.

The pandemic has sapped the flow of dollars from the island's tourism sector, which in 2018, its best year on record, generated more than $4 billion. Foreign workers' remittances slumped 22.7 percent to $5.5 billion in 2021, according to Reuters.

Economists say Sri Lanka's debt spiral was already on an unsustainable path even before the pandemic dried up the tourism fund, which accounts for 10 percent of the country's GDP.

And the misfortunes continued. The ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict has contributed to the downfall as Russia is one of the top buyers for the Sri Lankan tea industry. The conflict has also hiked fuel prices.

Apart from the debt crisis, the government's decision to ban chemical fertilisers to make agriculture 100 percent organic had a negative impact on the economy too. Experts say organic farming reduces production by half.

Sri Lanka's high dependency on imports for its essential items such as sugar, pulses, cereals and pharmaceuticals has only added to the troubles.

Experts said that successive Sri Lankan governments have been issuing sovereign bonds since 2007 without any plan to repay the loans. Further, reserves were built by borrowing foreign funds rather than a high earning through export services. This only exacerbated the foreign debts of the country.

During his 2005 to 2015 rule, Mahinda Rajapaksa, now the prime minister, opened the door to Chinese lenders. He borrowed heavily from China, eying to turn the country into another Singapore by building ambitious infrastructure projects, some of which ended up as white elephants.

From 2010 till 2015, Rajapaksa's final years in office, China poured $4.8 billion worth of loans into building the Hambantota port, a new airport, a coal-fired power plant and highways. By 2016, Chinese had loaned Sri Lanka $6 billion, fueling an infrastructure-building spree.

As a bitter lesson of this ill-planned drive, Sri Lanka, unable to repay a $1.4b loan, had to lease the Hambantota port to a Chinese company for 99 years in 2017.

The debt crisis has also dogged the coalition government of president Maithripala Sirisena, who ruled from 2015-2018. Political instability during this period didn't help the country either. After the highs of 12 percent economic growth in 2012, the country's growth hovered around 3-5 percent in subsequent years, only to take a plunge since 2019.

But it's not only the Chinese loan that Sri Lanka has to pay. The largest slice of debt that will mature in the next couple of years predates the Chinese lending boom. Those are from multilateral institutions like the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

Chinese lenders hold 10 percent of this $51 billion debt total, Japan accounts for 12 percent, the Asian Development Bank 14 percent and the World Bank 11 percent.

At a time when Sri Lanka badly needed access to international capital markets to keep its debt management programme on track, a series of downgrades by rating agencies in the wake of the pandemic in 2020 effectively locked it out.

The government has responded to the ratings agency downgrades with a mix of indignation, disbelief and denial.

Government officials believe the country can still manage to come out of this crisis betting on a huge upturn in tourism. In fact, the country's Department of Census and Statistics announced on Tuesday (March 29) that Sri Lanka's gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 3.7 percent in 2021 after contracting 3.6 percent in 2020.

In a sign of recovery, the main economic activities of the economy -- agriculture, industry and services -- grew by 2 percent, 5.3 percent and 3 percent respectively, the department said.

But are those figures enough to rescue the country?

After initially refusing to budge, Sri Lanka last week said it will seek World Bank assistance to stave off the crisis in addition to an International Monetary Fund (IMF) rescue plan.

It has sought help from its neighbours too. The government has raised swaps and credit lines worth $1.9 billion from India, and two more are under negotiation with Pakistan and Australia. Bangladesh has also provided $250 million loan assistance in August 2021 through currency swap.

Sri Lanka also received a $1.5 billion Yuan swap in December and the last tranche of a $1.3 billion syndicated loan from China arrived in September 2021. It has also asked for another $2.5 billion loan package from Beijing.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) this month said in a statement that the economy was in a better shape than some reports suggested. The CBSL said that it was committed to meeting all debt obligations and that suggestions Sri Lanka was close to default were wrong.

"The Sri Lankan authorities are pursuing a carefully thought-out plan which will ensure Sri Lanka's debt sustainability and economic revival," the Bank said.

Some analysts and opposition politicians, however, fear Sri Lanka may default this year.

"Sri Lanka's economy is experiencing multiple organ failures, and sepsis has set in," said Murtaza Jafferjee, chairman of the Advocata Institute, a think tank in Colombo, to The New York Times.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments