THE SONGS OF FREEDOM

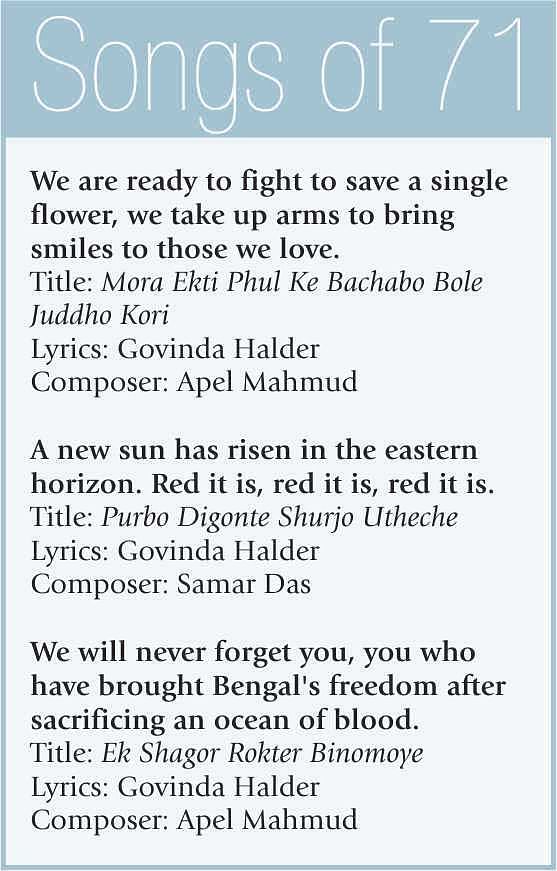

Powerful lyrics can be turned into lethal weapons. Even today we are moved by the songs of 'Joy Bangla'r Gaan' (The songs of freedom). These songs have remained in the hearts of countless individuals since their creation in 1971. Mora Ekti Phul Ke Bachabo Bole Juddho Kori, Purbo Digonte Shurjo Utheche and Ek Shagor Rokter Binomoye have inspired generation after generation of Bangladeshis. For these gems, we, the nationals of Bangladesh, will forever be indebted to Govinda Halder – the man behind the immortal words.

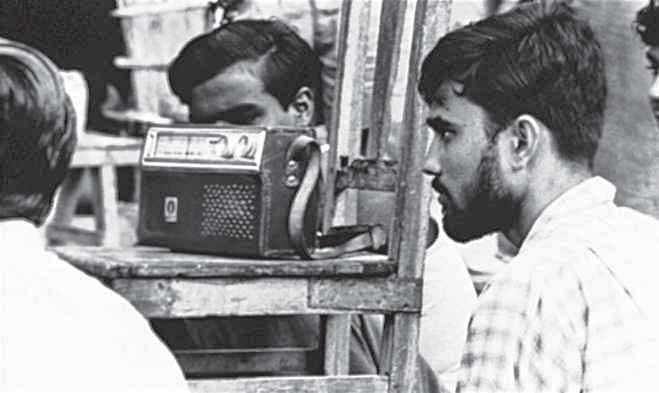

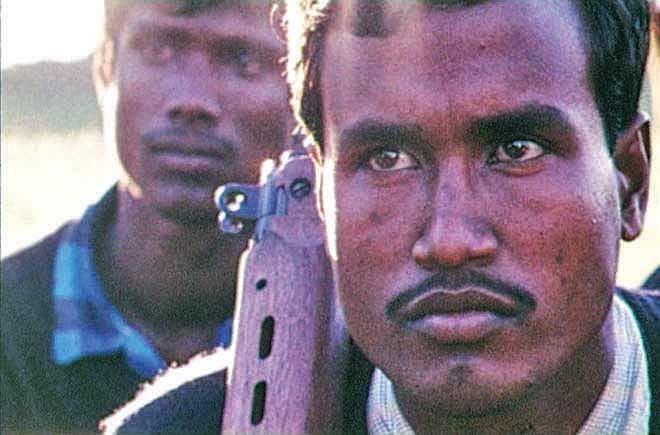

On March 25, 1971 - the war broke out in every corner of the country. With limited resources and abilities, people from all walks of life joined the struggle for freedom. By the end of May, Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra, a clandestine radio station of the resistance, started its second phrase, as it aired revolutionary programmes from Baliganj Circular Road, Calcutta (now Kolkata). And this became an invaluable instrument of inspiration during the war.

Apart from the news bulletins, it was the fiery, emotion-filled songs inspiring people to protest for a free Bangladesh that became an indivisible part of the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra. For freedom fighters and thousands fighting for their rights, this station and its patriotic songs were the only way they could endure the trauma, bloodshed and agony of war.

At that time, radio officials thought of introducing something new for their audience - something that would break away from the tradition of playing old recorded songs and regale them with rousing music performed live. Renowned activist and the news editor of the revolutionary radio station, Kamal Lohani, shared his desperate search to find strong lyricists with one of his friends Kamal Ahmed, who lived in Kolkata. Ahmed informed him about a young man, who wrote songs about the struggle of the people.

Lohani asked him to set up a meeting with the young lyricist. “While we were searching for a lyricist who could capture the essence of our country's struggle, Govinda Haldar appeared like a saviour with two notebooks loaded with 24 to 30 songs,” Lohani says.

At the beginning, Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra mostly broadcasted songs written before the war broke out. But the scenario changed completely during the war. Thus, there was a pressing need for new words and expressions. And that's exactly what Lohani found in Govinda Halder's diary.

The three of them met at a cafeteria in Esplanade, Kolkata. Govinda, wearing a kurta and a pair of simple trousers, took out two diaries from his bag. A label was boldly stuck on the face of the white cover – 'Joy Banglar Gaan.'

The lyrics had a sense of rhythm and went with the spirit of the war. Lohani liked the title but it was the intensity of the lyrics that left him dumbstruck. “In the sixties, during our movement against the Pakistani regime, we sang songs mostly written by Abu Bakkar Saddique, Akter Hossain and others. But during the war, the situation changed drastically. When I took a look at his lyrics, I knew I was at the right place at the right time,” says Lohani.

Hours passed, as one round of tea was followed by another. The young writer recited lyric after lyric from his diary, grabbing Lohani's undivided attention. At the end of the recitation, Lohani asked Halder for the diaries straight away. “He was a sensitive person and for that reason alone, he could sense the essence of our war and beautifully portray it in words,” explains Lohani. When asked for the diaries, Govinda Halder smiled quietly before handing them to Kamal Lohani.

At the revolutionary radio station Samar Das was one of the senior composers. Lohani gave the diaries to him for his consideration. Weeks passed. Das didn't have the time to even open the notebooks. One day Lohani asked composer Apel Mahmud about Halder's diaries, inquiring as to why nothing was being done about them. Hearing the details, Mahmud found his interest growing.

After going through Govinda's diary, Mahmud felt the pull of the inspiring words, and chose Mora Ekti Phul Ke Bachabo Bole Juddho Kori to render his composition. “I was quite sure this was going to be a historic song,” he wrote in the fortnightly magazine Tarokalok in 1984. He sat with his friend Ashraful Alam at night; both were ready with a harmonium and tape recorder. They created tune after tune but nothing satisfied them. Mahmud was not happy with the results. The next day, the duo again sat down for a fresh round of creative engineering, finally getting to the iconic tune that fills one with overwhelming emotion.

Ashraful Alam was completely bowled over by the song. In the dead of night, an excited Mahmud called engineer Shorifuzzaman and musician Manna Huq. While Manna Huq played the tabla, Apel was the vocalist. Finally, Mora Ekti Phul Ke Bachabo Bole Juddho Kori was aired on the first week of June. A great song was born, one that inspired thousands of individuals in the last 44 years.

After its immense success Samar Das didn't take much time and composed another legendary song from Govinda Halder's diary – Purbo Digonte Shurjo Utheche. An assorted programme with a set of sub-programmes like Darpan (where people spoke in Bangla), Recitation, Ranaveri (reports from different sectors), Kabikantha (poems recited by poets) were aired by the radio station called Agnishikha. Oikatan, one of the sub-programmes, which aired patriotic songs, was also a part of it. Purbo Digonte was aired at that programme.

Praise and criticism came hand in hand following the broadcast. Few people in Kolkata didn't approve of the lyrics Mora Ekti Phul Ke Bachabo Bole Juddho Kori and one of Kamal Lohani's friends asked him, “Are you fighting a war or falling in love?” Lohani replied, “It is a beautiful metaphor. And of course, one cannot fight for one's soil without being in love with it.”

On December 20, Halder penned another masterpiece – Ek Shagor e Rokter Binimoye – a true tribute to martyrs. It was written at the request of Apel Mahmud since the radio station was once again in need of a song that represented our struggle. They were in need of a song to pay tribute to those who laid down their lives to free the country. Govinda Halder took one day to write this legendary song.

Apel Mahmud and Govinda Halder sat in a small room at the radio station. Apel enthusiastically tried to compose the music. The first three lines went well. As Govinda wrote in Tarokalok in 1985, the initial three lines touched his heart but Apel found it difficult to follow this train of thought. “It became more and more difficult to compose the following lines. The phrases were lengthy. So at Apel's humble request, I had to remove some words to help him compose the tune.” It took two days to finalise the whole song. Almost immediately afterwards, Apel Mahmud began rehearsing the song with Swapna Roy, who was the lead vocalist of the song.

This is how we got the three revolutionary songs that are intertwined with our independence struggle. However, the struggle for the right of expression didn't end with the liberation war. Major General Amin Ahmed Chowdhury, Chairman of the Muktijoddha Kalyan Trust (Freedom Fighters' Welfare Trust) produced two cassettes on the songs written during the liberation war, titled Mora Ekti Phool Ke Bachabo Bole Juddho Kori. He faced resistance. Dictator Ershad was unhappy with the production, says renowned composer of Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra, Sujeya Soiam. “Amin had to leave his job after this,” adds Soiam.

In fact after 1975, all the records of the songs and the instruments that were used during their production at the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra arbitrarily disappeared. “Those who carried out the coup in 1975 tried their best to demolish all the inheritance of war. Now it is time to rethink about it and the government should re-release the songs with the accurate tunes and notes,” says Soiam.

During the war, Balal Muhammad wrote in his book Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra that there was a rule at the radio station – no foreigners could write or perform songs for the station. Thus, Govinda Halder's name was removed from the title list. Even after Bangladesh gained its independence, his name remained absent from the credit list.

“In June 1972 I went to Bangladesh to inform the Bangladesh Betar authorities about my concerns. After a bilateral agreement, they signed me on as an official lyricist and finally my name appeared on the title list of the songs,” wrote Govinda Halder in Tarokalok in 1985.

After 12 years of independence when he was writing the article he laments that even though the Betar made an agreement with him, he didn't get any royalty from the station or any concerned authorities. “They sent me vouchers from 1972 to 1973. I signed them. But despite that, they deprived me from this modest remuneration,” he adds.

It goes without saying that we neglected a song writer, who despite being a resident of our neighbouring country, put all of his heart and soul to pen the immortal songs that are sung at every programme observing our Victory or Independence Day. Thankfully, the government thought of paying its respect to him a few years back as a foreign friend who wrote with such passion for freedom.

The revolutionary lyricist is now critically ill. He is in financial hardship. He is unable to move or speak and is need of proper treatment, which he can't afford. It's now time for us to show our gratitude once more by standing beside the man whose words inspired millions to survive and emerge victorious over the genocide of 1971.

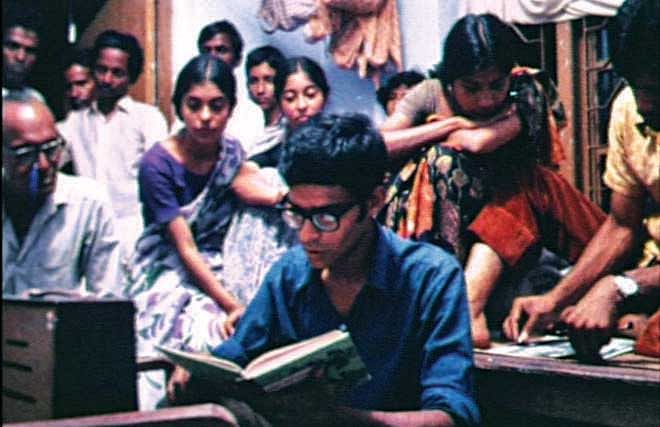

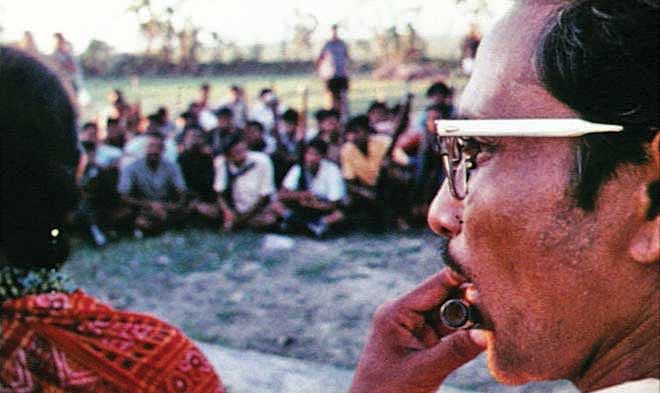

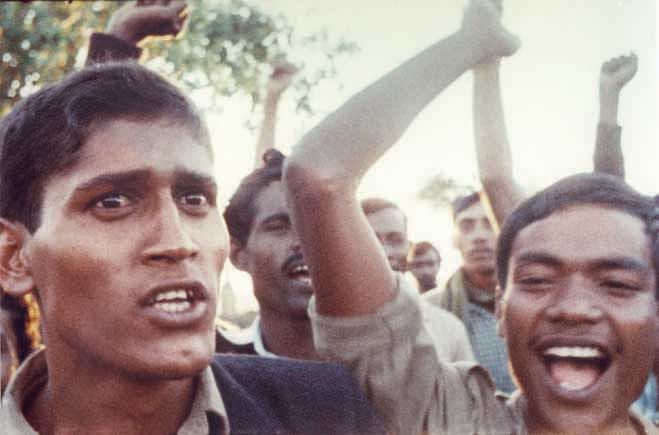

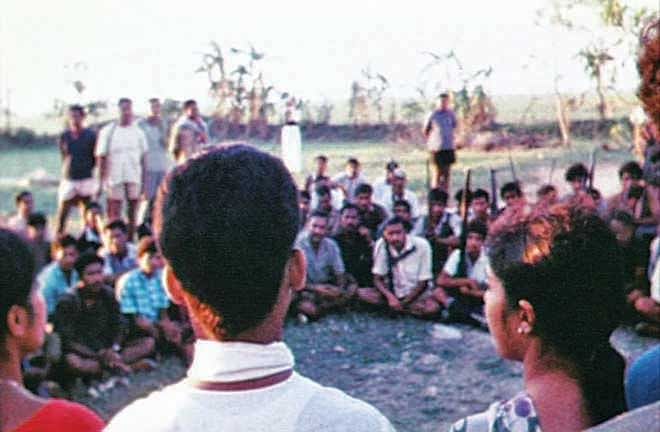

Images have been captured from the documentary film 'Muktir Gaan'.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments