The Plague in Bengal: Literary Glimpses and Anecdotes

About 122 years before the Covid-19 pandemic Bengal was struck by bubonic plague, which has left its traces in Bangla fiction and life writings. Punyalata Chakraborty recalls in her memoir Chhelebelar Dinguli (Childhood Days; 1958) that Rabindranath Tagore had once come to their residence to meet her father Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury and was then going by foot to meet his friend Jagadish Chandra Bose who lived nearby. Rabindranath returned unexpectedly, to report that he had spotted a dead rat lying on the pavement. He suspected that the rat had died of plague and feared that it might infect the passersby and the children playing near it. Rabindranath felt reassured only after Upendrakishore had the rat's carcass burnt down with kerosene oil. Punyalata's uncles were all praise for the poet, noticing that he was not lost in the world of thoughts but had a cautious eye on everything.

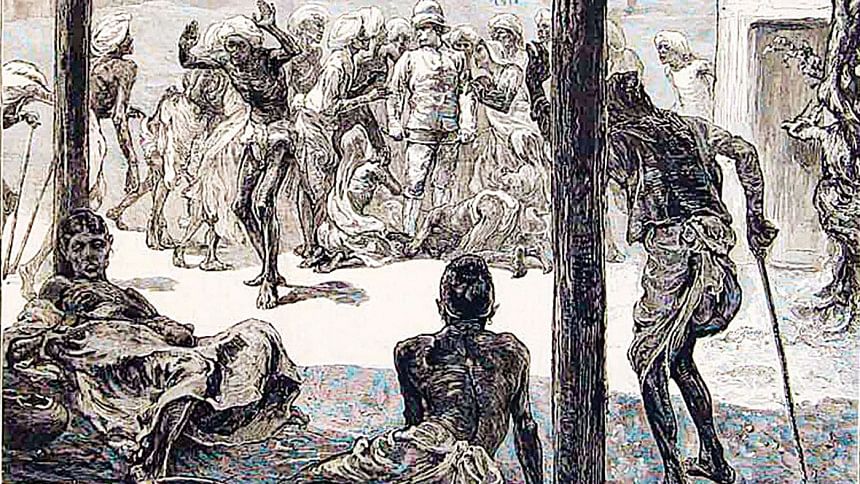

The first official case of bubonic plague in Kolkata was registered in April 1898. By 30th June 1900 the number of deaths from the disease in the city was 10,997, but the actual figure was probably around 13,000. Plague did not linger in Bengal like malaria or cholera and eastern Bengal was largely spared, but it raged over a decade or so. It was scary enough to haunt the popular imagination for a long time. Plague stands for great alarm whenever it is mentioned in Bengali literature.

Abanindranath Tagore recalls in Jorasankor Dhare (Near Jorasanko; 1944) that his uncle Rabindranath joined hands with Sister Nivedita to inspect Kolkata neighbourhoods during the epidemic. Rabindranath also started a private hospital for plague sufferers. This experience is reflected in Rabindranath's Chaturanga (Four Quartets; 1916). In the novel, a saintly atheist named Jagamohan refuses to escape to Kalna when the epidemic hits the city. He does not listen to his brother, the selfish and bigoted Harimohan. Instead, he converts his house into a private hospital to treat the poor Muslim leatherworkers of the locality. In the process, Jagamohan himself succumbs to the disease.

Jagamohan had to start a private hospital since he had found from his inspection of the government plague hospital that it treated patients like criminals. In fact, people feared the high-handed and obtrusive government officers more than the disease itself. Besides, people were concerned about preserving the purity of caste and the dignity of their womenfolk when faced with the possibility of medical inspection or forced admission to plague hospitals. Rumours circulated freely that the British government would inspect and inoculate all people by force. The suppression of plague was seen by many as an elaborate ploy for the conversion of Indians to Christianity. In view of this, the "Plague Manifesto" distributed by the Ramakrishna Mission in 1899 requested citizens not to panic or spread rumours. It tried to reassure them,"There will be no lack of effort in treating the afflicted patients in our hospital under our special care and supervision, paying full respect to religion, caste and the modesty (Purdah) of women." Saratchandra Chattopadhyay in Srikanta (1917) gives an account of the embarrassment caused by the open inspection of Rangoon-bound passengers at the Koilaghat jetty for plague. The narrator observes that the British doctor was touching and examining uninhibitedly such parts of the men's bodies (meaning, the glands in the armpits and the groin) as would mortify even a wooden puppet. The narrator adds, the "civilized" Indians were standing still after flinching only once under such treatment, but any other race would not rest before breaking the doctor's arm.

The novel Chaturanga seems to be unsympathetic towards Kolkatans who fled from the city for dear life. Similarly, the "Plague Manifesto" of the Ramakrishna Mission asserts, "Let the wealthy runaway! But we are poor; we understand the heartache of the poor. The Mother of the Universe is Herself the support of the helpless." It is recorded that the fare of palanquin and horse carriage rose fourfold to eightfold in response to the exodus of householders from Kolkata. Some, who could not afford even a bullock cart because of the inflated price and did not want to walk all the way, resorted to a scavenger's cart for moving out. However, this mass departure brings a refreshing change to the life of the feisty, proto-feminist heroine in the novel Subarnalata (1964) by Ashapurna Devi. Plague allows Subarnalata to take a train ride for the first time in her life. She also gets to live in the lap of nature for a while away from the claustrophobic house of her in-laws.

Pratham Alo (First Light, volume 2, 1997) by Sunil Gangopadhyay provides a snapshot of this exodus as seen by Rabindranath on his way from the Howrah Bridge to Park Street. The novel reports that non-Bengalis were rushing towards the Howrah railway station whereas those from eastern Bengal were making a beeline for the Sealdah station to escape the city. Pratham Alo also describes the brutal measures taken by the colonial police in the Kolkata slums in the name of checking the spread of the disease. It further mentions violent confrontations between the police and the local mob in Beleghata, Khidirpur, Baghbazar and Maniktala arising out of the government's approach to the disease.

All these accounts of the plague in Kolkata date from a time when the scare of the disease was a thing of the past, while the playlet Ashrudhara (The Shower of Tears; 1901) by Girish Chandra Ghosh was produced during the plague years. Curiously, the disease is personified as a character in this playlet, which was produced to lament the demise of Queen Victoria. It shows three friends, namely, Famine, Plague and Anarchy, jeering at the loyal Indian mourners and nurturing rosy hopes about their future exploits. Plague reports that Queen Victoria, a darling of God, had tearfully prayed to Him to rid the world of the pandemic. It is for this reason that she was sent from heaven to rule over the British Empire. Later, Plague indicates that his local address is in Burrabazar in Kolkata. He seems to have access even to the viceroy's palace. The playlet concludes with the hope that Victoria's son and heir will be as magnanimous and efficient as the mother. Ashrudhara premiered at the Classic Theatre on 26 January 1901, where the role of Plague was essayed by one Natabar Choudhury.

The most striking and gruesome picture of the plague in Kolkata is deftly provided by the novel Kolkatar Kachhei (Not Far from Kolkata; 1957) by Gajendra Kumar Mitra. The novel revolves around the fortunes of Rasmani, a pious and courageous high-caste Hindu widow. She goes to the Nimtala Ghat every morning at 4 o'clock to take a bath in the holy river. When the police prohibit access to the ghat because of the raging plague, she starts going there at 3 o'clock. One morning she steps on a half-burnt, headless corpse caught at the foot of the steps in the river. She realizes what it is - the corpse had to be dumped into the river because a funeral pyre could not be allowed to burn for more than two hours owing to the excess of corpses. But Rasmani is neither scared nor disgusted. On the contrary, she is full of reverence for the corpse. She is convinced that the corpse is as holy as Lord Shiva himself since it has been purified by the touch of fire and immersed in the sacred river.

Religion had a monumental role to play in the contemporary Bengali people's approach to plague. Premankur Atorthy reports in his memoir Mahasthabir Jatak that there was a rumour about the goddess of plague relocating to Kolkata from Bombay by the railway. However, she was not officially inducted into the Hindu pantheon. The "Plague Manifesto" of the Ramakrishna Mission specifies, "In order to remove the fear of the epidemic, you should sing Nâma Sankirtanam (the name of the Lord) every evening and in every locality." Besides, a letter to The Indian Mirror from an educated Bengali (published as a pamphlet in 1898) proposed a general day of prayer across all denominations. Generally speaking, people in Bengal have departed from such widespread, public religiosity during the Covid-19 pandemic and have privileged medical dictates over piety.

Abhishek Sarkar teaches at Jadavpur University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments