"Photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe." — Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), p. 3.

I begin with a conviction I borrowed long ago: that portraits of artists are never portraits of individuals alone. They are landscapes of history, shaped by turbulence, famine, betrayal, and survival. The painter's face, the sculptor's hand, the writer's solitude are never private signs. They belong to the collective, pressed upon by politics and myth. And so, when I entered Nasir Ali Mamun's exhibition of photographs of S. M. Sultan, I entered not merely the documentation of a man's life but a history of a nation glimpsed through one face, one hand, one shadowed room.

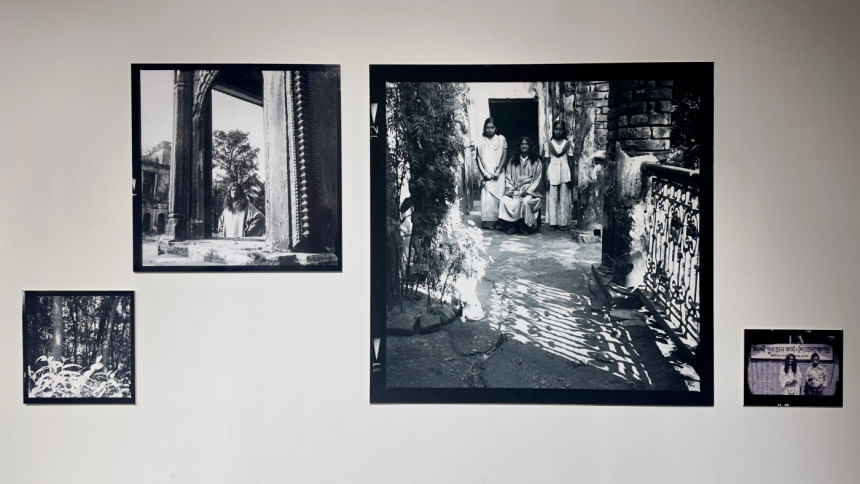

To mark the birth centenary of the legendary artist S. M. Sultan (1924–1994), Bengal Foundation, in collaboration with HSBC Bangladesh, is presenting Shotoborshe Sultan, a special photography exhibition by Nasir Ali Mamun. The exhibition opens on Friday, 22 August 2025, at 6:00 PM at the Quamrul Hassan Exhibition Hall, Bengal Shilpalay, Dhaka, and will remain on view daily (except Sundays) from 4:00–8:00 PM until 27 September 2025. The show features rare portraits of S. M. Sultan by Mamun, along with original negatives, handwritten letters, and memorabilia — many displayed publicly for the first time — offering an intimate visual journey from Sultan's village home in Narail to his later years. A commemorative catalogue titled Seeding the Soul was also launched on this occasion.

This occasion, then, is more than an exhibition. It is an act of remembrance, a gesture of reassembling memory into form. What Mamun began decades ago as a photographic testimony of a singular life now unfolds as part of a centenary constellation, where Sultan's images, letters, and fragments of existence are made present once more.

I have always thought of Sultan's canvases as counter-histories. He gave peasants monumental scale, men with torsos that seemed hewn from rivers, women whose muscles bore the sediment of centuries. In his paintings the agrarian body is not picturesque, not colonial ornament, but the truth of survival. It is the subaltern vision rendered as myth: peasants as the measure of Bangladesh itself. To see them on his canvas is to realise that history does not belong to statesmen or generals but to those who tilled, carried, endured.

But then I turned to Mamun's camera. What does it mean to photograph the man who monumentalised others? How does one make a portrait of the maker of counter-histories? The answer, I think, is to fold him back into the same life-world he exalted. And this is precisely what Mamun does. His black-and-white portraits of Sultan do not elevate him into the abstract figure of the artist. They embed him in the texture of everyday austerity: sitting on a mat in a broken zamindar's house, painting in the light that spills from an open door, eating with cats as companions, bent under the weak flame of a hurricane lamp.

At this point I cannot avoid a question that has always haunted photography: what power does the lens exert over the subject? There is always the danger of voyeurism, of reducing the subject to an image consumed by others. Portraits of socially significant figures risk becoming commodities of memory, consumed in the same way war images are consumed, stripped of their pain and turned into spectacle. I sense that Mamun is aware of this danger. His portraits of Sultan are not voyeuristic intrusions into a private life. They are careful negotiations with dignity. They refuse glamour. They refuse to turn Sultan into a celebrity detached from the world he lived in. Instead, they show him in fragile light, in humble space, in rhythms of ordinary survival. In this sense the photographs shape collective memory not by spectacle but by embedding the artist into the continuum of life he painted.

If I read these photographs through the grammar of cultural images, I find the expected: the artist at work, the studio, the brush, the profile of concentration. This is what I know, what the frame tells me, what I can read as part of an intelligible code. But then there are the details that prick me, details that break open the image. The hurricane lamp on the floor beside him, the shadow of a child at the door, the cat staring as he eats, the cracked floor that carries his weight. These details wound me because they refuse to let Sultan remain only as the category "artist." They insist that he was also a peasant, survivor, solitary body in fragile conditions. They pull him out of the frame of the familiar and force me to confront his life not as myth but as endurance.

I imagine what would have been lost if these photographs did not exist. Without Mamun, Sultan would remain only as a myth, his giant peasants in museums, his name repeated in art histories. But the man himself — the solitary meals, the brush held like a plough, the fragile glow of the lamp — would dissolve into rumour. These images resist that erasure. They say: the artist was here. He lived, he ate, he read, he drew, he breathed among children and cats, in broken houses, in dim light. They remind us that history is not only in canvases or books but in the texture of existence.

There is, in these photographs, a layering of time that unsettles me. I looked at Sultan sitting in a shaft of light in the 1980s, but I also saw the peasants of his canvases behind him, their monumental bodies pressed into his shoulders, their history folded into his posture. And beyond them, I see us, now, standing decades later in a gallery, staring. Time has collapsed into a single constellation: Sultan painting peasants, Mamun photographing Sultan, we watching the photograph, all three moments fused. This is how history flashes: not as a sequence but as a collision, where past and present confront each other.

It is tempting to see Mamun's portraits as biographical — Sultan in his house, Sultan with children, Sultan in profile. But to me they are something else: they are counter-archives. Just as Sultan painted peasants against the erasure of colonial and bourgeois art, Mamun photographs Sultan against the erasure of official histories that forget artists. Together they form a parallel historiography of Bangladesh: not the triumphant story of leaders, but the quiet story of endurance, peasants and artists, hands and brushes, cats and lamps.

When I look at the photograph where Sultan sits with children watching him sketch, I hear echoes of his own canvases. The children lean into the drawing, their small bodies mirroring the giant bodies he once painted. It is as if the continuum is complete: peasants on the canvas, children in the photograph, all carried into memory by the artist's hand. It testifies that art is not a private pursuit but a public sowing, a cultivation of imagination for the next generation.

Another photograph captures Sultan surrounded by cats at mealtime. On the surface, it is a domestic scene, almost humorous. But I cannot see it as humour. I see a man who shares his food with the voiceless, who lives without boundaries between human and animal, who inhabits a world of kinship with all that is fragile. This, too, is a subaltern ethic: the refusal of hierarchy, the recognition of survival as a shared condition. The peasants in his canvases, the cats on his floor, the children at his side — they are all part of the same vision of endurance.

What strikes me in Mamun's images is the play of light and shadow. Light falls not as spectacle but as intrusion: through an open door, across a mat, beside a lamp. Shadow thickens in corners, enveloping him. It is as though the photographs insist on mystery, on Sultan's refusal to be fully legible. The light does not reveal everything; it reveals just enough to remind us of what remains hidden. And this hiddenness is itself part of the truth. Sultan's art was not a complete explanation; it was a testimony to survival, to resilience, to strength. Mamun's photographs mirror that refusal: they give us presence, not clarity.

I do not see these photographs as neutral documentation. They are interventions. They place Sultan in the archive of the nation, but not as a sanitised genius. They show him as a man whose life was lived in continuity with those he painted. The cracked floor, the dim lamp, the brush like a plough — all of it insists that the artist's life itself belongs to the same subaltern vision he rendered in paint.

If I search for the deeper resonance of these images, I find it in their ability to create a new genealogy of memory. Official histories of Bangladesh elevate leaders, wars, institutions. But Mamun's archive says: the nation is also made of peasants and artists, of brushes and lamps, of lives lived in obscurity. This is not nostalgia. It is resistance. It resists the narrowing of history to power. It proposes another memory, one rooted in endurance.

I imagine Sultan looking back at us from these photographs, refusing to be tamed. His face is both weary and defiant, his body both fragile and monumental. In one image his eyes look past the camera, into some distance we cannot reach. That distance, I think, is the truth he carried: that peasants survive, that betrayal repeats, that art must testify. Mamun captures that refusal: not to look at us, but to look beyond us, into history's long arc.

Mamun does not elevate Sultan into the distance of celebrity; he embeds him in the texture of his modest, peasant-like existence. Here the studium is the portrait of the artist, recognisable, archival. But the punctum arrives in the details: the cracked floor beneath him, the hurricane lamp that doubles as muse, the open door spilling rural light across the mat. These images wound us into recognition: Sultan was not only the one who painted peasants into monumentality; he lived among them, bore their fragility, carried their solitude. Mamun's lens turns Sultan himself into a dialectical image — both artist and subaltern — inscribing him into the collective memory not as an untouchable genius but as a peasant of art, tilling images the way others till soil.

This, to me, is the core of Mamun's exhibition. It is not only about one man's life. It is about how the life of an artist becomes inseparable from the life of a nation, how his solitude is folded into collective endurance. Mamun does not let Sultan remain a myth or rumour. He makes him present, visible, fragile, and enduring. In doing so, he extends Sultan's own project: to monumentalise the overlooked, to give form to the truth that history belongs to those who survive.

There are two photographs that feel like fragments of cinema, set not in a studio but in the pulse of a rural bazaar. In the first, Sultan stands in a black long dress, absorbed yet porous to the flow of people around him. In the second, he wears a long panjabi, again surrounded by the crowd, his figure at once ordinary and magnetic. The mise en scène is elemental: the dirt ground, the scattered goods, the shifting faces of villagers, each detail arranged in a natural choreography that no director could stage. These are not static portraits but living tableaux, where Sultan's presence fuses with the everyday commerce of rurality. The images give the illusion of movement — bodies leaning, heads turning, gestures half-formed — so that one almost expects the scene to continue once the eye moves away. Compositionally, the crowd frames Sultan yet never isolates him, making him part of the same texture he painted: people as art, life as canvas. In these bazaar images, we see how Sultan's world was never elsewhere; it was here, among his own people, where his art and his life became indistinguishable.

And so I encountered the exhibition with a conviction that is no longer borrowed but my own: portraits of artists are never private images. They are constellations where past and present collide, where the brush in one man's hand carries the weight of a nation's soil, where a photograph of a meal with cats becomes a testimony of survival, where light falling through a broken door becomes the illumination of history itself.

I walk out of the gallery and carry the images with me, not as photographs but as fragments of a nation's unfinished memory. The hand with the brush, the lamp's small fire, the children leaning into the drawing. These are not records. They are interruptions, flashes, reminders that the artist's life was never separate from the fields he painted. I think of Sultan in Narail, I think of Mamun waiting with his camera, and I think of us, now, trying to remember. To remember is itself resistance, and the photographs keep that resistance alive.

Naseef Faruque Amin is a writer, screenwriter, and creative professional.

Comments