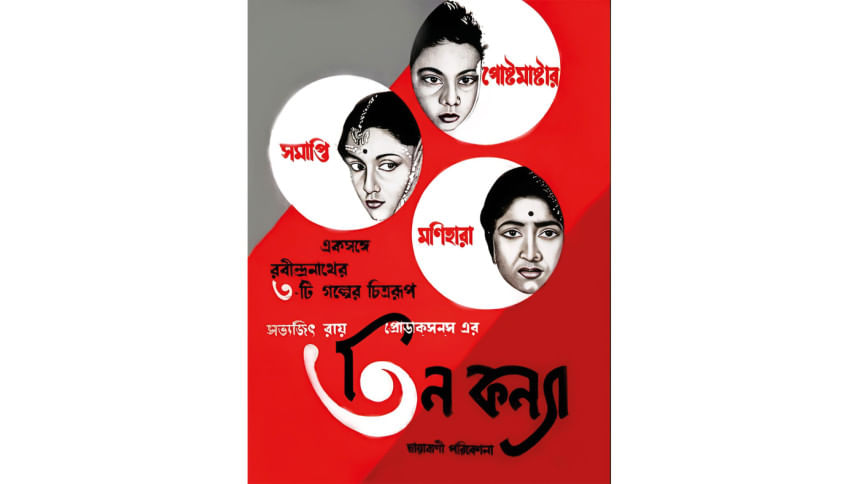

In 1961, Satyajit Ray made two films to make the centenary of the birth of Rabindranath Tagore. One was a conventional bio-documentary, the other a triple bill, Tin Kanya, based on three of Tagore's stories focussing on women. Ray would go on to make two more screen adaptations of Tagore's writing – Charulata (1964) and Ghare Baire (1984).

Before taking a close look at the three feature films that comprise Ray's tribute to Tagore we might note a few similarities between the two cultural giants. There is ample evidence in Ray's notebooks of his talent in the visual arts where we find countless illustrations of so many of his cinematic ideas, while Tagore took to painting when he was close to 60. Ray was more than competent as a musician, composing the music for all his films from Tin Kanya on, while Tagore wrote some 2,232 songs. Ray too was a writer – of filmscripts, of course, but also of detective stories and science fiction, of essays and criticism. It is a popular truism that Tagore wrote in one lifetime more than most people could read in a lifetime – novels, short stories, plays, essays and nearly 60 volumes of poetry. Both men had a global outlook that reflected their versatility. Tagore was a devoted Indian who yearned for his country's freedom, yet his artistry and intellect could never be limited by just that one country; Ray was also proud of his Indian heritage, yet was happy to take whatever he wanted from the cultures of other countries. Both men spoke and wrote in English as well as they did in Bengali. Both had close connections to the Brahmo Samaj, which lent them, perhaps, a more streamlined religiosity, and both were noted for their profound humanism. Both wrote a lot for children, writing that could also be enjoyed and admired by people of all ages. Both travelled widely and left their artistic marks in many different countries, yet were profoundly Bengali at heart, choosing to live and work in Bengal. Yet remarkable as Ray's artistic scope was, it could not match that of Tagore; indeed, no one's could. However, similarities such as this brief summation do suggest a closeness of the poet to the filmmaker.

Both travelled widely and left their artistic marks in many different countries, yet were profoundly Bengali at heart, choosing to live and work in Bengal.

The three films of the triple bill and the two longer films all deal with male-female relationships, and except for Postmaster, the first of the three short films, they all focus on marriage. It might also be noted that Postmaster and Charulata offer significant allusions to literacy and literature.

Central to the narrative of Postmaster is the notion of dislocation. Nandalal, a young man of the Calcutta bhadralok, is posted to a rural post office and is confronted by a totally different way of life, one into which he simply cannot fit, and this cultural or societal conflict is the sole cause of his constant and worsening depression. Eventually he applies for a transfer after contracting malaria and leaves the village – and presumably, rural life – for good.

Perhaps Nandalal does not elicit much sympathy, being what would seem to be a pampered and probably over-mothered city boy. However, a great deal of sympathy is ensured by Tagore and Ray for the little orphan girl, Ratan, who works as Nandalal's housekeeper and, when he is ill, acts as his nurse.

The literary interest in the film first emerges on Nandalal's arrival in his village home when he is seen unpacking some books. He takes one and reads it on the veranda. He lets some of the villagers know that he likes to write poetry and that he reads English literature. The reaction to this is one of sheer amazement. To ease his boredom he starts to teach Ratan to read and write. He does this for his own amusement, but to Ratan he takes on an almost divine status. When his happiness returns with the coming of his transfer, misery sets in for Ratan, who is assured of no more education and a return of her former loneliness. When Nandalal leaves the village, she does shed tears, but is championed by Tagore and Ray by maintaining a creditable dignity and showing a sign of maturity in pretending that she does not see him as they pass on the road.

The second film, Monihara, might seem somewhat out of place between the other two films. Indeed, when shown abroad, it was often left out to make the feature a double bill of two very different films with nevertheless a lot of relativity to one another. Monihara reveals a narrative of personal obsession and marital infidelity, which blends into a somewhat chilling ghost story. In fact, the film itself and the short story which it recreates are presented as a story read by a village schoolmaster.

The simple narrative deals with Phanibhushan's obsession with his wife, Manimalika, and her obsession with jewellery, her venality and her infidelity. Indeed, she elopes with a lover, while justice would seem to prevail when the boat on which they are travelling sinks and they drown.

We might note certain visual similarities with Charulata. The architecture and decor in the houses of Phanibhushan and Bhupati are notably Western in style as are the clothes that the two men wear. This serves as a reminder that the story-cum-film is set in two Indias – Indian India and British India - and that Tagore and, to a lesser extent, Ray, also lived through a time of two Indias. This point is rather significant in Charulata, but mostly it is merely cosmetic in Monihara.

The third short film is the delightful Samapti, which is remarkable for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that it is one of the earliest films to bring to the screen Aparna Dasgupta who, later in life as Aparna Sen, would achieve fame as one of Bengal's finest actors and one of the foremost filmmakers in India.

The focus here is the character of Mrinmayi, a village girl of much the same age as Ratan in Postmaster, but whereas Ratan is domesticated and responsible in her work, Mrinmayi – a veritable tomboy – is at one with the freedom of the outside, at play with her group of mostly boys and her pet squirrel.

The film is full of fun, as Postmaster is full of touching sentiment, most of it sad. It might also be said that Samapti's fun is more prominent in Ray's version than in Tagore's, for so much of it can be transmitted visually – somebody seen slipping over in the mud can be much funnier than being told about it by some lines in a book.

Like Postmaster, narrative progresses by development of the contrast between the two central characters; unlike Postmaster, Samapti ends in a union, not a separation. However, there is one element of melancholy here: Tagore would seem to be unconvinced about the rightness of the marriage of young girls, for Mrinmayi's endearing childlike features must fade as Mrinmayi the homemaker must emerge. Ironically, it would seem that her childlike features are what endear her to Amulya, as they indeed endear her to the film's audience.

There are distinct similarities between Postmaster and Samapti: both focus on a young girl and her relationship with an older, Western-educated man, and both have a rural context. But there are distinct differences too: a parting in one, union in the other; the poignancy of one, the light-heartedness of the other; simplicity of Postmaster, complex development of Samapti. Yet the two films compliment each other very well and strengthen the argument for Tin Kanya as a double rather than a triple bill.

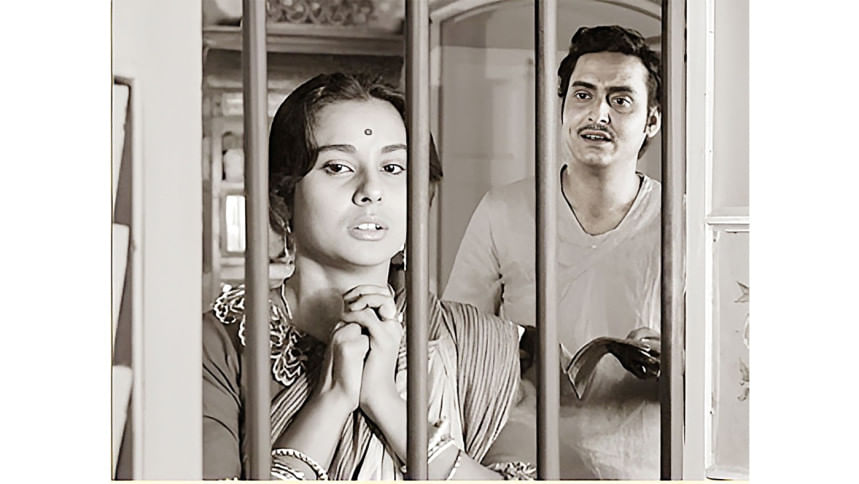

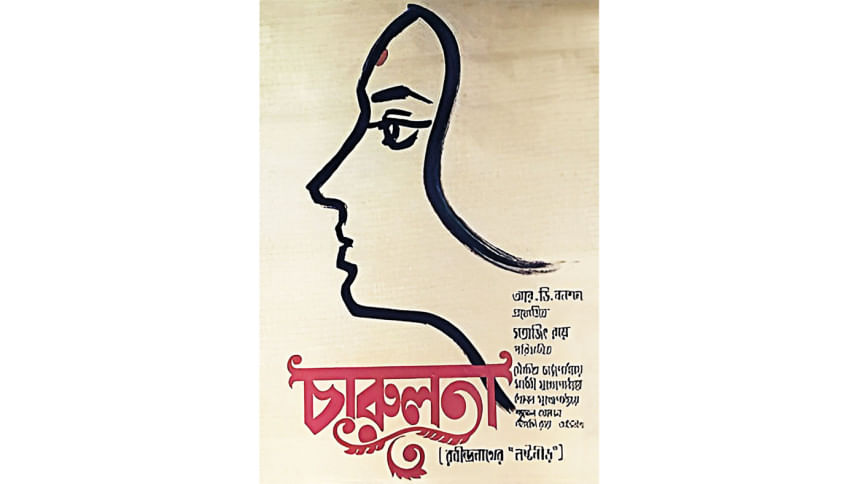

In 1964 Ray made the exceptionally beautiful Charulata, a film remarkable for its visual experience more than its dialogue. The opening titles roll over shot of a pair of hands embroidering the Roman 'B' on a handkerchief. (B for Bhupati, Charulata's husband.) The titles are immediately followed by Charulata's call to the servant for tea, and then there is a period just short of eight minutes without any dialogue at all. The visuals during this time show Charulata selecting a book - Bankimchandra's Kapalkundala - from a bookshelf, indicating both her literacy and her delight in Bengali writing. She also observes with evident delight the goings on in the outside world through a pair of opera glasses – a trainer and his two monkeys, a palanquin passing the house, an apparently amusing fat man. Then she sees Bhupati – in long shot coming along the upper storey veranda, lost in thought, not noticing his wife. He enters a room, from which he emerges a few moments later with a book, opened and claiming his full attention. This opening section very skilfully reveals Charulata as isolated – from the outside world, connected only by opera glasses, and from Bhupati. It also highlights her restlessness.

The shot of Charulata selecting the Bengali novel is indicative of her Bengaliness, or her belonging to the Indian India. Bhupati is very much inspired and preoccupied by British India, even by just Britain. He sees British political liberalism to be the great hope of civilisation, and it is this that drives his own newspaper, The Sentinel (in English, of course), the appeal of which is limited to the Western-educated elite of Calcutta; he has no interest in the Bengali writers so much loved by his wife. And so, while it would be quite wrong to say that the marriage is in any way a loveless one, it is to be noted that Bhupati is dedicated to his own work, which is steeped in British India, while Charulata is kept busy by her place in Indian India. However, it would indeed be missing the point to make a comparative judgement about the quality of each India, or to assert that one is worthier than the other. Both Tagore and Ray, I imagine, would come down on the side of an intelligent synthesis of the two. Unfortunately husband and wife remain separate from one other, and this dichotomy is at the heart of the drama that will develop.

Germane to this drama is the visit of Amal, a young cousin of Bhupati, a lively, spirited and educated young man; a vibrant and creative relationship quickly develops between him and the somewhat older Charulata. It is at first an innocent relationship, based on a mutual passion for writing (in Bengali). But as this literary passion becomes more and more intense, the relationship might be seen to take on the appearance of an affair. However, there is nothing in the novella or the film to give definite substance to this, except for an emotional moment when Charulata sobs intensely, embracing Amal with her face resting on his chest. It must be noted that this moment does have a profound effect on Amal - he does not smile or laugh again in the remainder of the film - and it would seem that his departure is inevitable.

It must also be stressed that Bhupati is a good husband and a loving one, and that Charulata is devoted to him. The opening line of the film shows her concern for the master's tea being late, a simple indication of wifely devotion. The slippers that she embroiders for Amal might be seen as extravagant in comparison with the mere handkerchief she embroiders for Bhupati, but the point of the slippers is to indicate naivete rather than unfaithfulness, and to allow a simple suggestion of Amal's rejection in leaving the slippers behind on the night on which he leaves the house.

As noted in an earlier context, Charulata is one of the 'Tagore' films marked by visual Anglophilia, particularly in the architecture and décor of the house and Bhupati's choice of clothes. This apparent Anglophilia begs the contrast to Charulata's passion for reading Bengali literature and writing in her mother tongue.

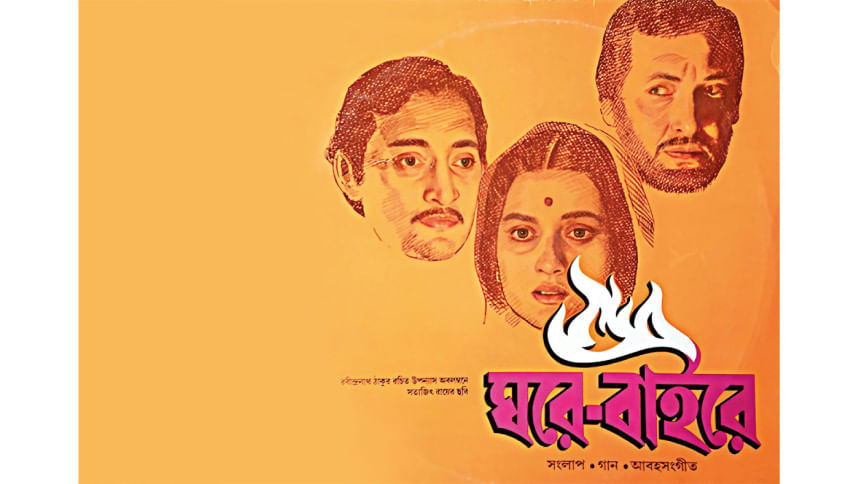

Twenty years later Ray made Ghare Baire, the first of his last last four films, indicating that much of the shine had gone out of his work. Ghare Baire is over-long and dense with dialogue, most of which is dry and polemical.

The contextual basis of the film is Curzon's Partition of Bengal in 1905 and the protests that mostly took the form of the public burning of foreign cloth, a form of protest to which Tagore was strongly opposed. The drama is structured around three characters: Nikhil, his wife Bimala and his close friend Sandip. The friendship would seem unlikely – Nikhil is gentle, rational and opposed to the protest fires, while Sandip is something of a rabble-rouser, an ardent cloth burner and organiser of demonstrations. Bimala is there for Sandip to try to win over, and as Charulata is infatuated somewhat by Amal, Bimala is infatuated for a time by Sandip. It is when the protests become violent that Nikhil orders Sandip to leave and Bimala realises her foolishness in being influenced by him. Ultimately Nikhil is killed in the midst of protest violence.

These five 'Tagore' films of Satyajit Ray make up a somewhat uneven group, but Postmaster, Samapti and Charulata stand out as masterly.

Dr. John W. Hood is a film critic, translator, and former teacher.

Comments