What Bolivia’s election can teach Bangladesh

The first round of Bolivia's national election, which took place on August 17, produced an unprecedented runoff and a decisive shift in the country's political balance. With centrist Rodrigo Paz leading on 32 percent and former president Jorge "Tuto" Quiroga second on roughly 27 percent, voters will return to the polls on October 19 under a clear two-round rule that requires either 50 percent plus 1 or 40 percent with a 10-point lead for an outright win. Notably, close to a fifth of ballots were null or blank—an outlet for protest, yet still counted transparently. Polling day itself was calm by regional standards, results were accepted as preliminary, and the system moved towards a conclusive second round.

Three design choices underpinned that experience. First, Bolivia separated a rapid preliminary tally from the official count, promising final certification within days while making preliminary data public on the same night. The new OEP's SIREPRE portal—an official, public-facing system—streamed these preliminary results in real time and was trialled openly ahead of polling day. Second, authorities welcomed robust international scrutiny: the European Union (EU) deployed around 120 observers, and the OAS mission issued a same-day preliminary assessment. Third, the law's runoff threshold ensures the eventual winner commands broad legitimacy rather than a narrow plurality.

Bangladesh's recent experience could hardly be more different. Its 12th parliamentary polls held on January 7, 2024 were boycotted by the principal opposition and widely criticised; Washington stated plainly they were "not free or fair," while rights groups documented a pre-election crackdown that poisoned the environment. Official turnout was just over 40 percent—a figure that, even if accurate, speaks to deep public disengagement.

Today, however, Bangladesh has an opening. The National Consensus Commission (NCC)—formed in February, with its tenure recently extended till September 15—has already brokered agreement on significant constitutional and electoral reforms, while circulating the July National Charter to parties for signature. Among the areas of emerging consensus are a law to govern the Election Commission, curbs on Article 70 to allow MPs to vote their conscience on key matters, independent delimitation, and opposition control of crucial parliamentary committees. The debates over a caretaker-style election-time government, term limits for the prime minister, and an appointments process that reduces partisan capture are ongoing but have shifted from taboo to negotiable policy.

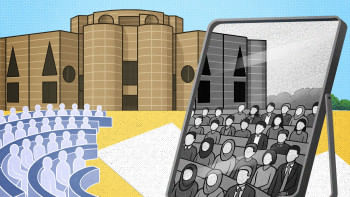

What, then, are the Bolivia-to-Bangladesh lessons the NCC should bring squarely to the fore? First, ensuring radical transparency in results. Bangladesh should legislate an OEP-style public portal for the next election that publishes, in real time, the image and data of every polling station result form as soon as it is logged, clearly labelling the feed as preliminary until the official tabulation is complete. Domestic observers should be guaranteed access to those same images for parallel vote tabulation (PVT), and parties' agents should be protected by law and police directives to obtain copies at source. The aim is not speed for its own sake but a transparent chain of custody that builds public confidence as the count proceeds. Bolivia's SIREPRE shows this is feasible with paper ballots and modest technology.

Second, credible, invited scrutiny is a must. The NCC should recommend an open invitation to full-fledged international missions (EU, Commonwealth and credible regional networks), with guaranteed nationwide access from pre-election through post-results dispute resolution. Bolivia's experience illustrates how such missions can help deter abuse and make technical recommendations that all sides can accept precisely because they stand outside the domestic trench war.

Third, bringing forth a winner that the country can live with. Our first-past-the-post system routinely hands a seat to candidates with thin pluralities in fractured races, which can tempt manipulation at the margins. The NCC need not copy Bolivia's presidential runoff, but it should consider recommending either ranked-choice voting in single-member seats or carefully piloted two-round runoffs where the winner fails to reach a floor (say, 40 percent). The goal is to raise legitimacy, not to engineer outcomes. If that feels too ambitious for 2026, the Commission can still propose ranked-choice pilots in city mayoral polls to build confidence and skills before scaling. Bolivia's two-round rule is explained in contemporary coverage and statute; the principle is what matters here.

Fourth, ensuring election-time neutrality with teeth. However it is structured—whether a revived caretaker format or a functionally equivalent, time-bound neutral administration—the mechanism must be codified and verifiable. That means a clear legal mandate, ground rules for police and administration postings, a transparent process for appointing and disciplining election officials, and rapid judicial remedies for campaign violations. The NCC's charter already outlines some of these elements; it should bring them together into a unified "election confidence package" to be applied in the 2026 election, with political parties pledging that the newly elected parliament will adopt it at the earliest opportunity.

Finally, name the stake. Bangladesh's last election was judged wanting and left scars. Bolivia's was imperfect too, with high protest votes, elite churn, and economic pain. However, its institutions offered citizens a visible, comprehensible path to closure. If the NCC can translate these lessons into enforceable rules, such as open data on results, protected observers, a legitimate mandate-building formula, and real neutrality, it can give February's election a chance to be believed. That, far more than who wins, is the reform the republic needs most right now.

Barrister Khan Khalid Adnan is an advocate at the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, fellow at the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, and head of the chamber at Khan Saifur Rahman and Associates.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments