We are Asiya: A battle lost, but the fight lives on

Asiya's sister cried, her voice shook as she spoke with a journalist, her sweet southwestern Bangla accent rang in my ears—a very familiar voice. It could have been my aunt, my grandmother, my cousin, someone very dear and beloved. I grew up with this warm accent wrapped around me. My family is from Jashore, and Magura is not too far. I have always identified with that place, and always will, even though I am not sure if I'll be able to bring myself to visit my real homeland again. I romanticise the idea that, perhaps one day, I'll be buried in my family graveyard there, and that'll be the next—and last—time I visit.

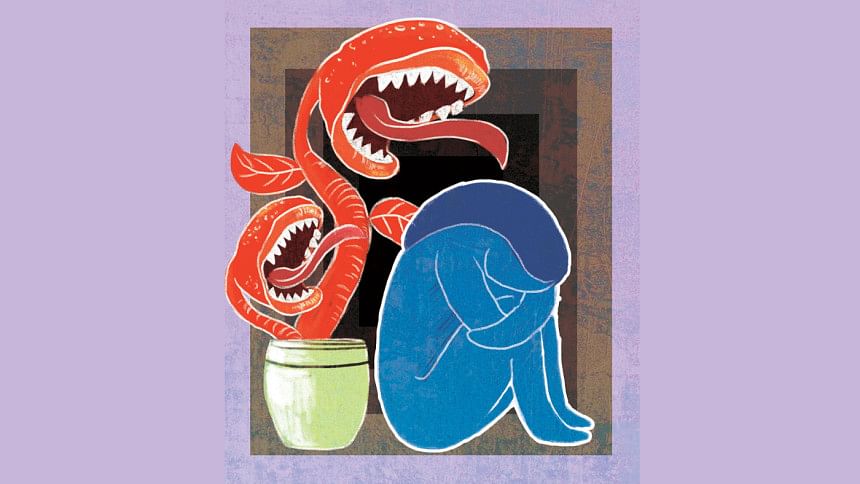

Injuries ran deep, the unthinkable cruelty shattered Asiya's tiny limbs and life. Asiya's sister said that even if she survived, she wouldn't have any value. Asiya didn't live to hear her sister's words, she didn't live to bear the burden of cruelty, but she fought valiantly. This is heartbreak upon heartbreak: even a child is not spared from having her value placed between her legs. Even Asiya's lonesome and gut-wrenching fight to return to this world alive was not enough to fulfil the measure of value placed on girls and women. Sexual harassment and trauma often ushers a girl child into "womanhood"—a painful, shocking and sometimes deadly experience is often the passage. Can we imagine the physical pain Asiya lived through during her last days? She lived through all of it, and it took three cardiac arrests to end her battle for life. It is a testament of her power and indomitable spirit, but why do we need our children to be so strong?

In this country, if a girl or a woman is not part of the rape statistics, she is lucky—at least, so far. It can happen to anyone, at any time, and can be done by anyone. No one, and nothing, is off-limits. Family members, elders, significant others, people we have just met, strangers—the list is non-exhaustive. Who hasn't been shamed or looked at because of the slight growth on the chest, and shamed because it was too little or too much for the age? If we start collecting data on body shaming alone, we can build one of the largest psychological case studies in history—an undeniable dataset of humiliation and hatred. Asiya did not need to be yet another cautionary tale for this nation. She was supposed to spend some time with her sister and then go back home. She was supposed to be colouring the pictures in her picture book, and the only borders she should have known were the borders outlining the figures in that book. And yet, we sent her to fight on the border between life and death and now she has drawn her final line—one that will never be crossed again.

Being raped is a matter of chance—being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Think about all the times you could have been raped, but weren't. Think about all the times you could be raped in the future, and if you have been raped and still living with the experience, then you are forced into thinking all the things you could have done differently to avoid bringing the unfortunate event upon yourself: only if you didn't get out that day, only if you didn't stay home that day, only if you didn't catch the eye of that one relative who lured you with chocolates so that they could inappropriately touch you, only if you didn't say yes to the guy who called you pretty, only if you didn't say no to the advances of the popular neighbour guy who blocked your way, only if you didn't get late at work that day.

Now, since women have to take the responsibility of provoking men, there is always a "because," a rationale—she was loud, too out there, her clothes were tight, her breasts too voluptuous. And if she's a respectable woman, why was she out so late or so early? What was a child's responsibility here, and what was Asiya's sister's responsibility, who was forcefully sent back to live with abusive in-laws?

Women are expected to plan their lives around the possibility of being assaulted/raped. Every step is a checkpoint. Shall we impart the same lesson to our children? We can teach them what's good touch and bad touch, we can teach them not to interact with strangers, we can teach them to say no to "friendly" offers, but what else? Who is responsible for making sure that no one strangles another Asiya, suffocates her, whisks her away in the middle of the night from her sleep, cuts and penetrates through her, puts her lifeless body on life support and murders her? The real question is, what can we teach the perpetrators and potential perpetrators? What is the responsibility of the one with power? Has revenge, retaliation and the death penalty ever worked?

It's easy to capitalise on Asiya's unfathomable suffering and death. Many influential people will speak, as they should, but please, can we stop putting people on a pedestal just because they're doing the bare minimum? When we fail our women, we fail our children. We fail the next generation, and we fail the future even before it can happen.

I wanted Asiya to live against all odds, and I wish she knew that she is a warrior and carried all our fears and pain even when she had no means to bear the weight we put on her. The youngest of this country are fighting the hardest battles. We have turned children into child brides, malnourished mothers, sex slaves, beggars in the streets, sweatshop workers, cleaners in people's homes, victims and survivors on the edge of death, stopping their journey even before they could dream of having a life. Asiya's tiny hands will never hold the life and future that we ripped away from her.

They say the heaviest coffins are those of children. Our hearts break for Asiya, but are our hearts strong enough to stick around and fight, or will we catch the next flight and leave? Leaving the fight is a privilege, but I will not blame any woman who is exhausted and doesn't have it in her to fight. We don't have to do the heavy lifting today. It's okay to mourn, to rest; resting is resistance as well. But the next day, we must come back so that Asiya's legacy is stronger than ever. This should never have been her battle. She was meant to grow, to dream, to paint the world in whatever colours that gave her joy. We are not too far from Asiya; we were once like Asiya, we love someone like Asiya, we are Asiya. Could Asiya be our turning point, our guiding force directing us towards justice? Will this be the moment we finally act on our words, "Enough is enough?" The blood of our daughters will drown us if we don't fight back. We women, we as a nation, owe this fight to ourselves.

Sarzah Yeasmin is a contributor to The Daily Star and works on the intersections of education and public policy. She is an alumna of Harvard University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our submission guidelines.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments