The Rohingya crisis: Empty promises, endless sufferings

Despite repeated international pledges and Myanmar's recent announcement to repatriate 180,000 Rohingya refugees, the reality on the ground tells a troubling and contradictory story. Over 118,000 refugees have fled to Bangladesh in the past year alone. Their perilous journeys, often undertaken by foot or sea, underscore the continued absence of safety, rights, and dignity in their homeland. These new arrivals lay bare the emptiness of Myanmar's repatriation rhetoric, exposing it as a performative gesture rather than a genuine effort towards justice or durable solutions. For Bangladesh—already hosting more than 1.3 million Rohingya since 2017—this renewed influx has reignited a humanitarian emergency, further straining infrastructure, essential services, and the already stretched resilience of host communities.

At the heart of this crisis are the refugee camps in Cox's Bazar—the world's largest refugee settlement. Initially intended for temporary protection, these camps have evolved into sprawling settlements of chronic vulnerability. The arrival of newly displaced Rohingya has pushed the system even further to its limits. With no land left for expansion, many new arrivals are forced to squeeze into already congested shelters or build makeshift homes on unstable, landslide-prone hillsides. In some shelters, 8 to 10 family members occupy a single room. This level of overcrowding is not only inhumane—it directly fuels fragmented health and protection risks. Poor ventilation and inadequate sanitation contribute to the spread of communicable diseases. Fire hazards rise with the density of makeshift structures. Hill-cutting to make space accelerates deforestation and erosion, making the entire landscape more vulnerable to climate-induced disasters. With the monsoon season approaching, the risk of floods and landslides adds another layer of danger to those already living on the edge of survival. In short, the new arrivals do not just stretch housing capacity—they elevate every associated risk and deepen existing vulnerabilities.

One of the most visible and immediate consequences of this increased population pressure is the growing food insecurity across the camps. The 2025-26 Joint Response Plan, developed by the Government of Bangladesh and humanitarian partners, was meant to address the needs of millions of people. Yet this plan is grossly underfunded, as global attention remains fixed on other crises in Gaza, Ukraine, and Sudan. In March 2025, the World Food Programme announced another drastic cut in food rations, reducing monthly support from $12.50 to just $6 per person. This amount is woefully inadequate to meet even the most basic nutritional requirements and sends a disturbing message to refugee families: that their survival is no longer a global priority. The fallout is already visible—UNICEF recently reported a 27 percent surge in cases of severe acute malnutrition among children in the camps within just one year. The newly arrived refugees, most of whom come after weeks of undernourishment and stress, now face an even bleaker situation. Without documentation, many cannot access immediate food assistance, leaving them dependent on already overstretched support systems. Moreover, this additional number creates a reality where the limited aid available must stretch even further. Current allocations, falling to roughly one-third of what was provided just a year ago, raise serious concerns about how long this fragile humanitarian response can hold.

Closely tied to food insecurity is the rapidly collapsing health system. Healthcare services in the camps were already struggling to meet the needs of the existing population due to overcrowding, dwindling supplies, and a lack of healthcare personnel. The recent influx has overwhelmed them further. Many of the newly arrived suffer from chronic conditions, injuries, untreated infections, and psychological trauma. Like previous waves of displacement, they come with extremely low health literacy, making it difficult for them to access care or follow treatment. While past years saw gradual improvements in health awareness due to continuous community engagement, such efforts are no longer feasible. Frontline health workers are now diverted to emergency services like nutrition stabilisation, outbreak prevention, and maternal care, leaving little room for outreach at the level required by the newly arrived. The camps are already reported to have a high prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS, which is expected to be high among the new arrivals as well, given the prevalence in Myanmar. This, along with cuts to food assistance, raises the risk of a further surge in HIV/AIDS, exacerbated by reported refugee involvement in prostitution and drug use, where local Bangladeshis are reportedly the primary clients. Meanwhile, mental health services—already minimal—are unable to meet the psychological needs of both newly-arrived and long-term refugees, despite widespread exposure to violence, displacement, and family separation. The recent cuts to United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funding, which supported programmes related to HIV/AIDS treatment, immunisation, and chronic disease management, have made matters worse, increasing the risk of preventable deaths and long-term disability. As more people arrive with urgent health needs, the fragile system edges closer to collapse.

Rising insecurity in the camps has also worsened. As aid dwindles and desperation mounts, armed groups and criminal networks have gained ground. Newly arrived refugees—unfamiliar with camp dynamics—are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. The influx has further strained an already fragile education system, mostly operated by NGOs.

Tensions are rising in host communities, where poverty, deforestation, inflation, and competition for basic services have fuelled growing resentment. Though the Rohingya movement is restricted, their involvement in informal labour markets—especially in agriculture and construction—has disrupted local livelihoods. Once grounded in compassion and shared identity, host-refugee relations are now fraying. Without urgent support and sustainable solutions, these tensions risk escalating into open conflict, threatening both humanitarian efforts and regional stability.

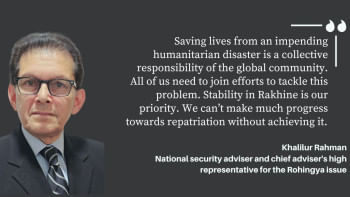

Diplomatically, the crisis underscores a profound failure of accountability. Myanmar's repatriation promises ring hollow, as people continue fleeing instead of returning. Despite clear evidence of genocide, there have been no meaningful reforms. The international community has failed to apply sustained pressure on Myanmar or adequately support Bangladesh. Generosity alone cannot carry the burden that Bangladesh bears. Without urgent global action—including funding, resettlement, and policy reform—the crisis will deepen. What's needed now is not more promises, but real commitments to justice and shared responsibility. This is not just a logistical challenge; it is a test of global humanity.

Dr Md Nuruzzaman Khan is research fellow at the University of Melbourne, Australia. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments