Jamie Miller exists in real life, we just don’t want to admit it

Nila Roy, a Class 10 student, was making her way to the hospital with her elder brother in the Bank Colony area of Savar on an ordinary September day back in 2020. All of a sudden, she was attacked and brutally stabbed to death by a young boy named Mizanur Rahman. Investigation later revealed that Mizan had been persistently stalking and harassing Nila for a long time. Upon facing rejection, he resorted to fatal violence.

Then, fast forward to May 2023, Mukti Rani Barman, 15, was similarly attacked when walking home from school in Netrakona. Her stalker, 19-year-old Kawser Mia, had been harassing her for some time. After Mukti rejected his advances, he responded with a brutal, public stabbing that claimed her life.

Now, if you have binged Netflix's global hit Adolescence, Nila and Mukti's cases might sound eerily familiar, no?

Although this British drama is not based on real events, its unsettling portrayal of online misogyny, toxic masculinity, and the rise of the manosphere might remind you that while Adolescence is fiction, the murders of Nila and Mukti are not.

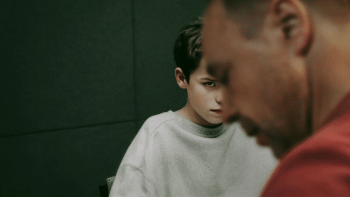

Tightly shot, masterfully plotted, and emotionally gripping, the four-part miniseries gained massive global attention almost immediately after its release. As the story unfolds, 14-year-old Jamie Miller is arrested on suspicion of murdering his classmate, Katie Leonard.

At first, Adolescence toys with us: did he really do it or not? But it doesn't take long for the truth to settle in, as Jamie's crimes were caught on CCTV. So, instead, Adolescence shifts the focus to figuring out why Jamie killed her. As the co-creator Jack Thorne puts it, "This isn't a whodunnit, but a whydunnit."

Beyond each episode's continuous-shot brilliance, Owen Cooper's gut-wrenching debut, Stephen Graham's masterful writing, and of course the "not just a cheese sandwich" metaphor, Adolescence asks us a very uncomfortable question: why are we so unnerved by Jamie Miller? Is it disbelief that a boy so young could commit such an adult crime, or is it that he feels painfully familiar?

Who raises the Jamies of our world?

The show may not be based on real events, but co-creator Stephen Graham, who also stars as Jamie's father, Eddie, mentioned in an interview that the story was inspired by articles he read about young men stabbing young girls to death.

One of those cases was likely the murder of 12-year-old Ava White in Liverpool back in 2021. A 14-year-old boy began filming Ava and her friends without consent, and Ava confronted him, demanding that the footage be deleted. As the confrontation escalated, he stabbed Ava in the neck, leading to her death.

Another likely inspiration was the murder of 15-year-old Elianne Andam in 2023. She was walking to school when she saw her friend in a confrontation with her former boyfriend, 17-year-old Hassan Sentamu. Elianne intervened. Sentamu, feeling "disrespected," pulled out a kitchen knife and stabbed Elianne fatally in the neck.

But unlike typical portrayals of violent offenders, Jamie's background complicates things. A middle-class teenager raised by loving parents in a stable home, with a sister he seems to care for, there are no obvious signs that suggest he is capable of such violence.

The show devotes significant attention to Eddie, Jamie's father, and his emotional process of accepting that his son is a murderer.

Jamie looked up to Eddie, because Eddie embodied everything society says a man should be: strong, stoic, sporty, loud. Jamie recalls being put into football, which he wasn't good at. What he remembers is not encouragement, but his father looking away, ashamed, convinced the others were judging them both.

Jamie figured out he wasn't good at the things men are expected to be good at. Maybe that's what drew him to the internet, where, unlike football, he got to decide what he liked and didn't. Where he felt power, control.

The show smartly connects schoolyard dynamics with the darker corners of the internet, as it reveals Jamie's victim Katie was allegedly bullying him after turning down his offer.

Jamie wasn't even romantically interested in Katie. But when her nudes were leaked, and Jamie joined the crowd consuming her humiliation, he saw a chance to approach her when she was vulnerable, thinking "she was gottable at that point." But Katie rejected him, backing up with public bullying.

Some of the slangs she used—like "incel" or "involuntarily celibate"—refer to online communities of men who blame women for their lack of romantic or sexual success.

It's a digital echo chamber of rage, where theories like the "80/20 rule" circulate, claiming 80 percent of women only want the top 20 percent of men. Or the red pill/blue pill metaphor, where red-pillers believe women hold all the cards, and men like them are victims.

Children learn to regulate emotions slowly. The problem is that emotions have been gendered. Boys are often told to "man up." So, they learn to translate shame, grief, guilt into anger—the only "acceptable" male emotion that gives them a sense of power.

From a very young age, many boys are conditioned to believe a real man is dominant, desired, and always in control—especially over women. So, when that doesn't happen—when a woman says no—it feels like a betrayal. Like being exposed as a failure at being a man. Most boys aren't given the emotional tools to deal with that. They reach for what they believe they're allowed to feel: anger, blame, control.

Because being angry feels powerful. Blaming someone lifts shame. Revenge feels like reclaiming what they think was stolen from them.

Jamie, Mizan, Kawser, and the killers of Ava and Elianne followed the same emotional trajectory. It doesn't begin with a desire to harm. It begins with the belief that they were denied something they were owed—and that someone must pay.

Some audiences even blamed Katie for "pushing" Jamie over the edge. The narrative, sadly, isn't that unfamiliar.

Take Jahidul's murder case, just days ago; he and his friends were chatting near their campus when a fight broke out over claims they were laughing at two women nearby. When things turned deadly, rather than the attackers, the women were questioned, ridiculed, even blamed for the murder they had nothing to do with.

Because in patriarchy, blaming women is easier.

In the most discussed third episode of Adolescence, during Jamie's session with psychoanalyst Briony Ariston, he admits to feeling ugly and rejected by girls. He justifies stabbing Katie by saying he showed "restraint"—that he didn't touch her "like most men would."

Briony doesn't soothe or affirm him. That infuriates Jamie. He screams at her, becomes verbally violent, and tries to humiliate in the same online bullying language he grew up with—trying to dominate the session.

Deep down, he knows he's going to be held accountable for killing Katie, and no amount of screaming at Briony is going to stop that. But by trying to control the conversation, especially with a woman, he thinks he can reclaim some power.

But when Briony signals the guard off, it irks Jamie as he realises she's the one with the real control in that room, not him.

When first dropped on Netflix, Adolescence felt like fiction teetering too close to reality. Jamie Miller is a pattern, a chillingly familiar shape we've seen before, in news headlines, in police reports, courtroom statements, and morgues.

What connects Jamie to Nila, Mukti, Ava and Elianne's murderers is that they are all products of everything we have normalised but should have questioned. They are loud, flashing warnings of a social failure. The tragic result of letting boys grow up without being taught how to lose, how to be vulnerable, and how to take no for an answer, laughing off "boys will be boys" while ignoring the very real violence that phrase can cloak.

Adolescence also sticks to a familiar script, women doing the emotional labour while men unravel. We see it in Briony Ariston, the psychoanalyst tasked with decoding Jamie's mind, absorbing his rage without flinching. The show dwells in Eddie's grief—a father mourning a son who's still alive—while offering far less space to the inner worlds of Manda and Lisa, Jamie's mother and sister. While Eddie breaks down, Manda and Lisa stay composed and calm, coping in silence, holding the family together.

But maybe from "how could he do it," the focus should have shifted a bit to the question no one asked: why didn't Lisa turn out like Jamie?

Same household. Same parents. Same internet access. Same world. Why didn't she turn out to be a murderer as well?

We may never fully know why, but boys like Jamie don't become murderers overnight. They're shaped slowly by a culture that mocks male vulnerability and rewards dominance, labelling it as masculinity.

So, when many dismiss shows like Adolescence, maybe the real discomfort lies in how accurately it reflects that we have all seen the real Jamie Millers, too closely.

Ayesha Humayra Waresa is a freelance writer and student of mass communication and journalism at University of Dhaka. She can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments