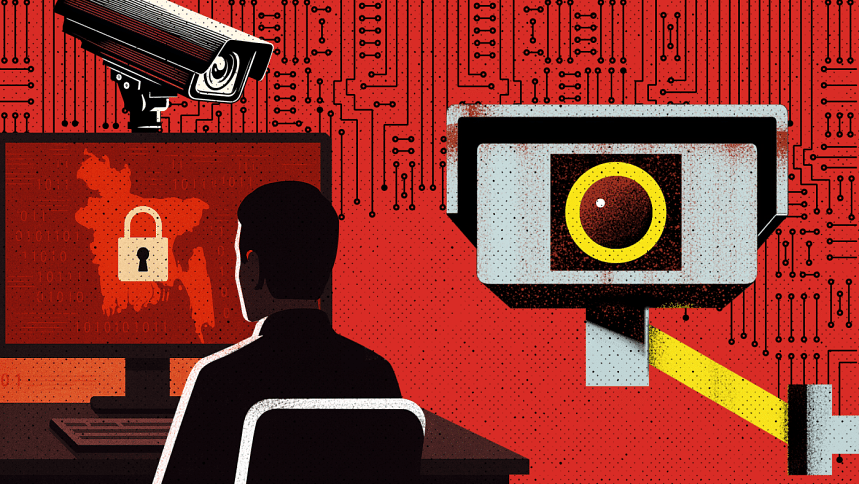

How Bangladesh has been building a digital police state

Bangladesh, like many modern states, has a deeply embedded architecture of a surveillance state. But ours was not constructed overnight; it was forged in crises. From the presidential assassinations of the 1970s and 1980s to the attempted assassination of a foreign diplomat, from paramilitary mutinies to terrorist attacks over the last two decades—each national trauma has become a justification to tighten the government's grip on citizens. With each incident, the surveillance apparatus grew stronger and less accountable. What started as a response to security threats has morphed into a system for political consolidation and control.

Since the early 2000s, successive governments have steadily restructured Bangladesh's legislative and regulatory landscape to normalise expansive surveillance. Under more than 15 years of Awami League rule, this system has enabled the routine suppression of dissent, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings. Yet, this shift has not occurred in isolation; all arms of the state have been complicit in normalising a surveillance regime that undermines the very principles it claims to protect, whether through active enforcement, silence, or institutional abdication.

Surveillance at the source

Bangladesh's surveillance capacity does not begin with a camera; it begins with a budget line. In FY2023-24, over Tk 63,000 crore (approximately $5 billion) was allocated for the Ministry of Defence, the Armed Forces Division, and the Public Security Division—the institutional core of the country's civilian and military intelligence apparatus. This sum feeds the backbone of Bangladesh's surveillance infrastructure, yet how much is spent on technologies that track, profile or monitor citizens remains undisclosed. There is no parliamentary scrutiny and no statutory human rights protection guiding procurement decisions.

According to an investigation by Tech Global Institute, between 2016 and 2024, the country's law enforcement and intelligence agencies procured over 200 surveillance devices and software systems, although the actual number is likely higher given the opacity surrounding these transactions. These include IMSI catchers, GPS trackers, drone systems, facial recognition technologies, and communication intercept tools—acquired without any meaningful public consultation, export-import controls or legal safeguards.

While laws like the Public Procurement Act, 2006, the Public Procurement Rules, 2008, and the Import Policy Order establish standards for transparency, competition, and import regulation, these frameworks remain conspicuously silent on human rights. There is no legal requirement for the authorities to conduct due diligence or audit to ensure that imports capable of tracking, profiling or monitoring individuals are compliant with the Constitution of Bangladesh or international human rights obligations. Worse still, procurement decisions made "in good faith" are insulated with legal immunities, effectively shielding them from challenge even when rights are violated. In the absence of robust accountability mechanisms, state actors encounter little institutional friction for overreach and, in many cases, are incentivised to pursue it. By design, therefore, the laws are structured to allow systemic and sustained impunity, shielding state actors from legal challenge while leaving citizens with no meaningful avenue for redress.

A legal system built for control?

Existing legal and regulatory architecture governing surveillance in Bangladesh is a fragmented patchwork of laws that confer expansive, largely unchecked powers to state agencies. Tech Global Institute research found that more than 20 different laws enable surveillance. Often, terms like "monitoring" and "interception" appear repeatedly across laws, not as narrowly defined legal authorisations, but as vague placeholders that open the door to arbitrary surveillance under the catch-all justifications of public safety and national security.

At the heart of this framework lie legacy statutes such as the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulation Act, 2001 and the Telegraph Act, 1885, which allow the executive branch to monitor, intercept, record, and collect vast troves of user data throughout the entire telecommunications value chain—from international gateways to mobile network operators and internet service providers. These provisions are neither accidental nor incidental; they are rooted in colonial-era and colonial-inspired statutes designed for domination, not democracy. Their continued enforcement in the 21st century reflects a deliberate choice in statecraft, one that preserves a legal order that treats citizens not as rights holders, but as subjects to be monitored, managed, and marginalised.

Complementing the statutes are licensing conditions issued by the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) that, in effect, institutionalise surveillance as a non-negotiable requirement of doing business in the sector. Clause 25 of the 4G licence agreement, for instance, obligates mobile network operators to enable real-time access to user information, bulk data interception, and live database monitoring by security agencies like the National Telecom Monitoring Center (NTMC). Operators must also identify and report users flagged as national security threats. While the exact nature of compliance remains opaque, these obligations are likely carried out without meaningful user knowledge or informed consent. What is clear, however, is that compliance is not optional; it is enforced not only through the threat of criminal prosecution and financial penalties, but also through coercive administrative pressures such as licence non-renewal or permit withholding, making resistance commercially untenable. Nevertheless, the silent acquiescence by multinational subsidiaries reflects a profound abdication of corporate responsibility, and raises serious concerns under both domestic legal standards and international frameworks such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Government surveillance overreach is not limited to telecommunications. An illustrative example is the collection and retention of expansive demographic and biometric datasets by the Bangladesh Election Commission under laws like the Representation of the People Order, 1972 and the National Identity Registration Act, 2010. Once collected, these datasets are routinely cross-linked with other databases, including health records, passport data, banking information, and tax filings maintained by other state agencies. Data flows across these networks through opaque bureaucratic pipelines, leaving citizens visible to power, and power invisible to them.

Even more concerning are the state's intelligence agencies operating in near-total darkness. Central state intelligence agencies like the NTMC, the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI), and the National Security Intelligence (NSI) operate without public-facing mandates or accountability. Other surveillance behemoths—like the Special Branch, Police Bureau of Investigation (PBI), Criminal Investigation Department (CID), Counter Terrorism and Transnational Crime (CTTC) unit, and Rapid Action Battalion (Rab)—are only nominally governed by colonial-era laws like the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1898, Special Powers Act, 1974, and Police Act, 1861, with their methods often outpacing both legal text and judicial oversight.

Violation of constitutional rights

These sweeping powers have gutted the very rights the constitution promises in at least two critical ways. First, the lack of legal clarity and institutional accountability undermines articles 31 and 32, which guarantee equal protection under the law and prohibit the deprivation of liberty without due process. Second, while articles 39 and 43 allow the curtailment of fundamental rights to privacy and freedom of expression, such restrictions must be reasonable and grounded in legitimate aims such as national security or public order. In practice, however, these safeguards are routinely ignored, reinterpreted or bypassed altogether. What was meant to be the exception has become the norm.

Exacerbating this structural permissiveness is a judiciary that has largely remained on the sidelines. Unlike comparable jurisdictions such as India, where courts have articulated strong constitutional limits on surveillance, courts in Bangladesh have remained largely passive. A rare exception is The State vs. Oli (2019), in which the High Court held that warrantless, routine collection of telecommunications data violates the right to privacy under Article 43 of the constitution. Yet, no clear guidelines were issued, nor has there been consistent judicial oversight since. Surveillance continues, undisturbed and unaccountable.

Rather than reversing this trajectory, emerging policies appear to entrench the status quo. Take, for example, the proposed Personal Data Protection Ordinance, which adds newer dimensions of risk. With expansive exemptions for crime prevention and national security, and vague provisions for data localisation, the law risks legitimising, rather than restricting, invasive surveillance. History has shown us that such provisions function less as protective safeguards and more as tools for consolidating state power in Bangladesh.\

A panopticon state by design

Bangladesh now possesses the infrastructural capacity to watch more people, more closely, and for more arbitrary reasons than at any other time in its history. Surveillance in itself is not inherently illegitimate; the state has both the right and the responsibility to ensure national security and public safety. But over the past three decades, the balance between liberty and control has tilted decisively away from constitutionalism and towards authoritarianism. Surveillance is no longer a targeted tool; it is the default operating system of governance. It is embedded in the circuitry of daily life, normalised through bureaucracy, and reinforced by fear. What stands today is the quiet entrenchment of a panopticon state. The result is an Orwellian reality in which the state sees all, knows all, and answers to none.

Despite its reported extensive use during the 2024 "Monsoon Revolution" and promises of reform by the interim government, no meaningful efforts have been made so far to dismantle or restrain this machinery of control. Too many lives have already been lost, too many freedoms eroded, for the state to persist in these excesses. Now is the time to act, not with rhetoric but with reform. And it must be done with urgency and resolve, to honour those who have suffered and to ensure that such abuse is never repeated.

Shahzeb Mahmood is the head of research at Tech Global Institute, where he leads on platform accountability, surveillance, and data protection.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments