Democracy in the digital age: Lessons from Bangladesh and beyond

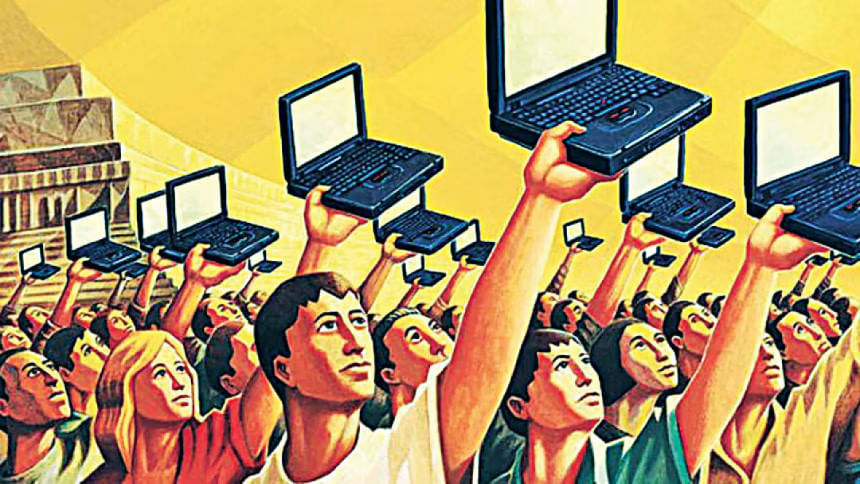

Few men sitting thousands of miles away, on another continent, with no direct ties to a country's political parties, can have a significant impact on a revolution, challenge state narratives, and shape public perception in ways unimaginable just a decade ago. Their words can now be amplified by social media algorithms and reach millions in an instant, able to rally support, create dissent, and shift political discourse in almost real-time. This is not a hypothetical scenario anymore; it is our current reality. The recent wave of political awakening, the July uprising in Bangladesh, was heavily fuelled, in part, by various independent digital influencers who dissected state affairs, criticised government decisions, and reshaped public conversations, all without setting foot in the country.

This is the power of digitalisation. The internet, once a mere repository of information, has evolved into the most formidable arena for political engagement, where narratives are created, contested, and reshaped in real-time.

In today's world, the internet has become an interwoven part of our lives. We are consistently spending a significant portion of our waking hours online. A fundamental shift in human behaviour through the way we communicate, engage, and interact, is being witnessed. A new societal standard has emerged where the internet is the primary source of news, education, and information.

The smartphone has taken centre stage as the first point of contact for knowledge, socialisation, and work. Online meetings have replaced many in-person interactions because they are often more convenient. The time saved from not having to prepare, travel, and for physical meetings makes virtual alternatives the preferred choice. This trend has created a digital landscape where industries thrive, relationships form, and opinions shape without the need for physical presence. We are living in a digital society, and the younger generation is driving this transformation at an even faster pace.

This change is especially noticeable in the political sphere. Conventional methods and policies are finding it difficult to adjust to this new reality. Political parties that only use conventional strategies, like offline outreach and live rallies, are losing ground. On the other hand, those who utilise digital platforms in addition to real-life rallies are gaining traction and interacting with the public more successfully.

An effective illustration of this phenomenon is the July uprising. In recent years, numerous affiliated political parties have made several attempts to mobilise the populace in favour of governmental reform, democratic reforms, and sometimes for their own interests. These attempts, however, were mainly unsuccessful in organising any noticeable masses. However, what established political parties were unable to accomplish for years, a small group of students somehow succeeded in doing.

These students resonated with the public because they operated masterfully in the space where most people now spend their time—online. They spoke the language of the digital generation, understood their concerns, and connected with them on platforms that mattered. While jobs and family responsibilities dominate everyday life, the online world has now become the primary space where people engage in discussions, form opinions, and participate in movements.

By unlocking this digital space, the student-led movement was able to unite people around a common cause and translate online momentum into real-life action on the streets. Digital presence was not the only winning factor, but it was indeed a great amplifier to keep the momentum of the uprising going.

Now it doesn't necessarily mean that the value of the old-school on-the-street politics is dead. We cannot forget that despite a large amount of dissent being expressed against the previous government online, the mass people had to come to the streets to actually see the end of the regime. This goes to show that the online presence of the new youth political leaders shouldn't divert them from learning the tricks of the street. If they wish to move forward towards long-term leadership, they will also have to learn quite a bit of the traditional political culture of Bangladesh.

This digital transformation is not unique to Bangladesh. We have seen similar movements worldwide, where social media played a pivotal role in mobilising people. The 2010-2012 Arab Spring served as an example of how political dissent could be amplified through digital platforms. Social media sites like Facebook and Twitter helped activists in Egypt and Tunisia plan demonstrations, disseminate real-time information, and mobilise support from around the world.

More recently, the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States saw unprecedented digital activism, where viral videos and hashtags (#BLM) brought police brutality and racial injustice into global consciousness. The problem existed throughout modern history, but the consciousness was shaken due to this impactful digital movement. The rise of digital-only political candidates further proves this point. Figures like Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Ukraine, who built much of his presidential campaign through digital engagement, and Nayib Bukele in El Salvador, who uses social media as his primary governance tool, show that traditional political structures are eroding. Voters are increasingly influenced by direct, unfiltered online engagement rather than party machinery and conventional political institutions.

If any case validates the power of digital persuasion, it is Cambridge Analytica. While widely condemned for unethical data use, what it truly exemplifies is how digital platforms can shape political behaviour at an unprecedented scale. By leveraging psychological profiling, Cambridge Analytica was able to influence the perceptions of millions of voters during the 2016 US presidential election and the Brexit referendum—in the two most powerful democracies in the world.

It was about accuracy, not just false information. Their microtargeting efforts crafted messages that struck a deep chord with people, reaffirming their convictions and influencing them to take particular political positions. This approach demonstrated that policy debates on debate stages and at campaign rallies are no longer the only way to win elections. Rather, the hallmarks of contemporary political warfare now include algorithmic influence, data analytics, and digital strategy.

This pattern is also present in Bangladesh. Political parties are dooming themselves if they disregard digital engagement as being less important than traditional campaigning. Voters are actively influencing political messages online rather than merely passively consuming them, which is a stark reality.

There are obvious repercussions for political parties that only use conventional structures: they become irrelevant and eventually fail. Parties that don't adjust to new technology eventually lose their base, as history has demonstrated.

Donald Trump's 2016 victory in the US was propelled by a digital-first campaign that made use of Facebook advertisements, Twitter, and grassroots online activism. Even though Hillary Clinton was a seasoned politician, she was unable to match the Trump campaign's digital energy, which outperformed her in online outreach.

Even during the 2019 UK elections, Boris Johnson's Conservative Party prevailed thanks to incredibly successful online campaigning, while the Labour Party lost its worst defeat in decades as a result of its inability to fully comprehend the potential of digital mobilisation.

While digital democracy is empowering, it is not without its dangers. The very tools that can fuel political engagement can also be weaponised for misinformation, polarisation, and manipulation. The same algorithms that drive engagement also amplify sensationalist content over facts, creating echo chambers that distort reality.

For this reason, regulation is required. The Digital Services Act and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union have established a standard for how countries can protect online speech while maintaining the accountability of digital platforms. To stop social media from being abused during elections, nations like Germany have implemented strict laws against hate speech and disinformation online.

Bangladesh needs to follow suit. Political parties must change not only to win elections but also to maintain the morality, equity, and transparency of digital democracy.

The future of democracy in Bangladesh depends on how well we navigate this digital revolution. The lessons from the July uprising, Arab Spring, and Cambridge Analytica's microtargeting are clear: the digital space is now the true battleground for political engagement.

Political parties that fail to adapt, innovate, and safeguard digital democracy will be left behind. But those who harness the power of technology while ensuring transparency, ethical engagement, and responsible governance will shape the political future.

The digital age is here, and democracy must evolve with it. The question is not whether politics will go digital—it already has. The real question is: can our parties adapt to it?

Ashfaq Zaman is the founder of Dhaka Forum and a strategic international affairs expert.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments