50 years on, Sheikh Mujib’s killing deserves a nuanced reading

During 1974-75, all the opposition political parties wanted Sheikh Mujib's ouster, but it was not possible to remove him through street agitation. He had amended the constitution and concentrated absolute power in his own hands, leaving no constitutional or electoral means to change the government. Therefore, it can be said that, in a way, he himself had created the conditions conducive to a potential removal from power.

At that time, Sheikh Mujib's popularity had hit rock bottom. If we look at the backdrop, apart from the Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB) and Muzaffar Ahmed's NAP (National Awami Party), every political party outside of BAKSAL wanted Sheikh Mujib's downfall. That downfall eventually came, but it happened through a military coup—and a brutal one at that.

After the horrific tragedy of August 15, 1975, many were forced to accept it, many were stunned, some were saddened, and some were happy—we saw a range of reactions. As a result, those on the outside welcomed the coup, while Mujib's followers remained inactive. Some were arrested, some went underground, and quite a few fled to India.

Afterwards, a vacuum was created within Awami League, which then saw multiple internal splits. Such coups happened in various countries around the world—they were bloody, and in many countries, the head of government was killed. What was exceptional here was that in Sheikh Mujib's house, all the family members present were killed. The same thing happened in two other houses—the homes of Sheikh Fazlul Haque Moni and Abdur Rab Serniabat—because they were close relatives of Sheikh Mujib. I would say that the coup was, on the one hand, an Awami League-centric political overthrow, but at the same time, it was an attack on the family of Sheikh Mujib. There were two elements: one was the change of power, and the other was the massacre. Both happened together.

One thing is clear here: the incident that took place in 1975 was not unprecedented. Similar events have occurred in some other countries. After the Russian Revolution, all members of the Tsar's family, who were in captivity, were executed; we called that a revolution. In Iraq, when the monarchy was overthrown under the leadership of Brigadier Karim Qasim, all members of the Iraqi royal family were killed. These are just two examples I can think of; there may be more. So, historically, this was not the first such incident.

However, I would say that killing Sheikh Mujib might still have been given some form of political legitimacy had he been the only one killed. But killing all his family members had no moral legitimacy whatsoever. Among those killed, his two elder sons faced allegations for many reasons, and people may have harboured resentment against them. But the way his wife and youngest son were killed had nothing to do with the coup, and the killing of his two daughters-in-law was nothing short of cold-blooded murder.

Sheikh Hasina has always said that Sheikh Mujib's assassination was the result of a massive conspiracy, with many players working behind the scenes. After 1975, she had plenty of time—she was in power for 20 and a half years in total. She repeatedly claimed that the masterminds behind the scenes would be identified and brought to justice. She made politics out of it, but never managed to form a commission of inquiry. Had she set up such a commission, it could have shed light on the matter. This shows that she was not truly serious or sincere about investigating Sheikh Mujib's assassination; rather, she used it for political gain.

In the years following Sheikh Mujib's assassination, his positive image was gradually revived. This continued until the election at the end of 2008, when Sheikh Hasina came to power. Then it became clear that Sheikh Hasina could not think beyond her own family. For her, the country, the nation, and the party all revolved around her family. She began building establishments in her father's name, her mother's name, her brothers' names, her grandparents' names, and so on. Many universities were established under Sheikh Hasina's relatives' names. Ironically, in so doing, the image of Sheikh Mujib, which had gradually been restored, once again began to erode.

During Hasina's regime, freedom of expression, freedom of the press, and the ability of opposition political parties to operate all came under threat. Finally, last year, widespread protests against her rule swept the country. We witnessed a mass uprising in which, outside of Awami League, practically every party and its supporters united. At one stage, Sheikh Hasina was overthrown and she fled to India. But in people's eyes, Sheikh Mujib became the symbol of Sheikh Hasina's misrule and tyranny because Sheikh Hasina had ruled by using Sheikh Mujib as a political commodity.

Though Sheikh Mujib himself was not responsible for Hasina's misrule, people began to see him as the icon of that authoritarianism. His statues were pulled down, all the establishments bearing his name were changed, his house in Dhanmondi—which had been turned into the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum— was attacked and demolished. In the end, he became a victim of his daughter's misrule.

In Bangladesh today, there are still two opposing views about Sheikh Mujib. One side believes that he was a great hero of history, that without him, Bangladesh would never have become independent. The other side believes that Sheikh Mujib was a traitor, that he deceived the people, and therefore, the fall of a traitor took place. These two streams of thought represent a kind of psychological civil war between two camps. I see no possibility of it being resolved unless one group completely annihilates the other, metaphorically speaking. That's how the situation continues.

A question might arise about how we should view the coup or Sheikh Mujib after 50 years of his assassination. The answer lies in the fact that human beings have both good and bad qualities. All things considered, it is difficult to place a person on a scale and assign them a score.

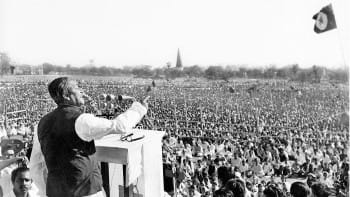

There is no denying that Sheikh Mujib was the main leader of the nationalist movement in this country, and the Liberation War was fought in his name. Until 1971, he could be called the great hero of this nation—he had no rivals in politics. From 1972 onwards, however, he exercised state power, and many opposed him. So, in the post-1971 period, we see him as a ruler. At one time, he was a leader loved by the masses; later, he became a ruler disliked by many.

Combining these two phases, what score should we give him, and what is Mujib's place in history? Where does he stand? If we are to judge that, we must inevitably look back and acknowledge the process of forming a nation-state through the bloody war of 1971, from which we achieved our independence. Therefore, as long as this country exists, we cannot erase Sheikh Mujib from our history.

Mohiuddin Ahmad is a writer and researcher of Bangladesh's political history.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments