Meeting Amar Mitra: The anguish of a complete Bengali author

AMAR Mitra's literary achievements are formidable. His works of fiction have won India's coveted Sahitya Akademi Award (for the novel Dhrubaputra) as well as West Bengal's Bankim Puraskar (for the novel Ashwacharit).

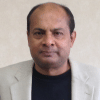

But you wouldn't be able to tell if you met the man. The diminutive, sexagenarian veteran fiction writer is disarmingly self-effacing in person, as I discovered when I met him at an Atlanta literary event in his honour hosted by Seba Bangla Library. His trip was sponsored by Galpapath and BoierHut.com, two organisations devoted to Bangla literature.

Born in Bangladesh's Satkhira, he moved to West Bengal in the 1950s when he was an infant. His mother's heart never quite left their birthplace, Mitra said. He spent his childhood listening to his homesick mother's sweet, sad, nostalgic reminiscences of the home they had to leave, the Kapotakkha river made famous by Michael Madhusudan Dutt.

Many, many years later, when Mitra had an opportunity to visit his birthplace, he was overwhelmed with emotion. As he reconnected with a place he had left in childhood, he told attendees at Seba Bangla Library, he carried on an imaginary conversation with his mother. "This is it, Maa. I'm going to leave now. But I'm going to leave you behind. You stay here at your baaper bari (ancestral home)."

It was a deadpan, matter-of-fact description. Mitra spoke in a low monotone, with charming gentleness and humility, but his words packed a powerful emotional punch.

I, like the rest of the audience, sat stunned, deeply moved by the emotional power of the heart-rending anguish his remarks reflected.

This, then, is a microcosm of what the 1947 Partition of the Indian subcontinent has wrought. We are aware of the terrible communal riots at that time. What tends to be ignored are the terrible fissures in the hearts of families and individuals left by the geographical divide.

Mitra has been writing for over five decades. His body of work includes 30 published novels, a number of short-story collections as well as a number of books for children. Yet he is not quite done. Even now, he sits down to write each morning.

For his award-winning novel Dhrubaputra, he did considerable research, reading historical documents as well as brushing up on his Sanskrit. Set in Kalidasa's time several millennia ago in the Madhya Pradesh city of Ujjain, the novel is actually a rebuttal of the social-cultural environment described in Kalidasa's epic. The drought-ridden Ujjain threatened by misrule and rising autocracy is entirely the product of Mitra's imagination, which was affected by the disquieting contemporary socio-political environment at the time of writing, Mitra acknowledged.

Later, Mitra read a short story of his published in Bangladesh's Kali O Kolom, and his abiding sympathy for the vulnerable ordinary human being, caught in the awful socio-political environment of vicious antagonisms, became evident.

Mitra continues a distinguished tradition championed by some of the most renowned exponents in Bengali literature. That is why I consider him, like them, to be a complete Bengali writer. What I mean is that he is an author whose work embraces the region in all its diversity and transcends the terrible Hindu-Muslim divide that has bedevilled it. Like literary forbears Kazi Nazrul Islam, Sunil Gangopadhyay and Hasan Azizul Huq, his worldview is a plural, inclusive one. Perhaps not entirely coincidentally, Gangopadhyay and Huq, like Mitra, have personally experienced the trauma of exile. There are other distinguished writers who were exiled after partition, yet never wavered from their deep, abiding faith in a humane, inclusive Bengali identity—Muzaffar Ahmed, originally from Bangladesh's Sandwip, founder of the West Bengal's CPM, economist Ashok Mitra and historian Tapan Ray Choudhury of West Bengal, literary scholar Anisuzzaman of Bangladesh.

We live during a particularly distraught age, when divisions—racial, ethnic, religious, you name it—seem to be tearing apart human societies. The rise of ethno-nationalism and sectarian chauvinism is darkening the political horizon all over the world.

The trauma of the 1947 partition also left enormous bitterness and pain in its wake. Yet all the writers I mention, including Mitra, not only transcended it, but embraced a humane, inclusive ethos that gives me enormous comfort as I consider today's fraught age.

During his lecture in Atlanta, Mitra said that he firmly believed that, in his words, "every Bangladeshi has a right to visit Rabindranath Tagore's Jorasanko mansion, and anyone from West Bengal has a right to visit Jibanananda Das' Barisal."

Mitra expressed his fond wish that people would rid themselves of sectarian enmities that continue to cause so much violence, pain and misery. In a short story, he ends with a deeply affecting fantasy: The protagonist wakes up to discover that human beings live in harmony and borders have disappeared.

Notwithstanding the pain and bitterness after having to leave his birthplace, Amar Mitra, it turns out, refuses to give up on his dream of a society where people, despite their differences, live in amity.

What a wondrous coda at a time when we seem to be sinking deeper and deeper into our vicious sectarian prejudices! Amar-da, weighed down as I am by cynical scepticism of the human race, I cannot say in all honesty that I feel terribly optimistic. But I salute you from the bottom of my heart for having the largeness of heart to continue to dream.

If you are right, and I am wrong, I'll be the happiest person on earth.

Ashfaque Swapan is a contributing editor for Siliconeer, a monthly periodical for South Asians in the United States.

Comments