‘Centuries of scientific, technological and economic progress maybe lost in the next few decades’

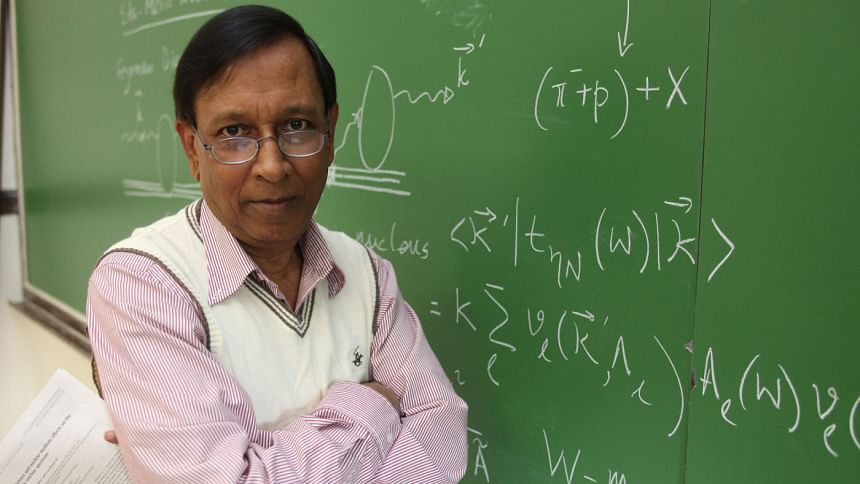

This week, in The Daily Star's new interview series that aims to give readers an idea of what changes to expect in a post-Covid 19 world, Dr Quamrul Haider talks to Badiuzzaman Bay. Dr Quamrul Haider is a professor of physics at Fordham University, New York. Prior to joining Fordham in 1988, he was a research associate at the prestigious Los Alamos (New Mexico) and Lawrence Livermore (California) National Laboratories. An author of numerous research papers in high-impact physics journals, he received Bangladesh government's Independence Day Award in 2012 (in the science and technology category). In this interview, Dr Haider talks about the double whammy of Covid-19 and climate change and the future of humanity in an increasingly vulnerable planet.

Contrary to what many hoped, the Covid-19 crisis has failed to unite humanity for their own survival. It continues to be a polarising factor, rather than a unifying one, as world leaders bicker over petty issues. As a scientist, how do you view the global response to this virus?

I think the threats of Covid-19 and of human-induced climate change have united people who care about public health and the wellbeing of our planet, but failed to unite the world leaders. In responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, a unified global approach led by the World Health Organization (WHO) has been thwarted by autocrats like the US President Donald Trump and others. They are using the chaotic situation created by the pandemic as a weapon for propaganda, repression and arrogant show of strength. The crisis offered them an opportunity to trash their rivals, display their vast powers and, in some instances, subvert democracy.

While the world looked up to the United States to lead the fight against Covid-19, Trump played down the severity of the virus. He has, in his familiar way, contradicted the experts by spreading misinformation and seeding false hope in the minds of the people. He savages anyone who questions his credibility. Instead of leading the world in these times of great distress, Trump put himself in the company of quack doctors who promote phony elixirs and sell miracle cures for a long list of medical conditions.

But this is not the first time world leaders have failed us. Since the 1980s, scientists have been warning that to limit the most damaging impacts of climate change, strong policies are needed to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. Ignoring their warnings, politicians allowed greenhouse gases to build up to potentially dangerous levels in the atmosphere. The reason: most likely their short-sightedness, or lack of knowledge about climatology. Many of them are also beholden to the fossil fuel industry.

Nevertheless, since 1995, world leaders have met every year at the Conference of Parties to forge a global response to the climate change emergency. At these dysfunctional conferences, they along with their sycophants have given recycled speeches that were "full of sound and fury, signifying nothing." Except for the Paris Accord hammered out in 2015, they failed to deliver strong commitments to tackle the terror unleashed by climate change. Can we, therefore, hope that in future conferences they will be able to agree on implementable plans to deal with climate change head-on? I don't think so.

Within the first two decades of this century alone, there have been outbreaks of deadly diseases, which shows the world's increasing vulnerability to threats arising from new pathogens and epidemic-prone diseases. What does the future look like to you?

I am not an epidemiologist. Nonetheless, by looking at the history of epidemics, it is obvious that the emergence of new diseases is inevitable. The microscopic agents or pathogens responsible for these diseases will always find ways to exploit any weaknesses in our defence system set to fight against them.

Every virus mutates. It is part of the virus' life cycle. In some cases, mutations may actually lead to a weaker virus. For example, many of the diseases we call common cold are Coronaviruses. They may have been virulent in the past, but they mutated to become merely a nuisance now. As Covid-19 makes its way around the world, there are predictions that the virus will mutate, but at a slower pace. Scientists believe that when it will mutate, the new copies could be deadlier than the present one.

Hopefully, just like other pandemics, Covid-19 will ultimately become a disease like the common cold. It is too early to predict though when that will happen. There will also be a vaccine or better medicine to treat it, but until then, people are going to die. Although Trump claims that Covid-19 has already been reduced to "ashes," experts warn that the pandemic is far from over, and we should expect a second wave soon. And in many countries, including Bangladesh, it has not yet peaked.

What chance do we have against these emerging, 'shape-shifting' threats?

Scientists all over the world are racing to find out more about Covid-19, and our understanding may change as new information becomes available. They already identified several strains of the virus. We would, however, like to know whether reinfections after recovery are possible. Scientists are also working tirelessly to develop vaccines, and are hoping to produce one as soon as possible. It usually takes several years to come up with a safe and effective vaccine and antiviral drug. But if Trump is re-elected and continues to withhold funds earmarked for WHO, it could possibly take decades to find a cure. Therefore, our focus should be on prevention so that we can stop pandemics before they start. To that end, we can no longer go back to what was normal six months ago. Instead, we have to adapt to the present lifestyle for years to come.

Eventually, our responses to this health crisis will shape the climate crisis for decades to come. In particular, the efforts to revive economic activity after the pandemic, without changing our lifestyle and without cutting down on greenhouse gas emissions, may reverberate across the planet for thousands of years.

In a recent article, you drew a similar connection when you talked about how the global crisis of Covid-19 is an eye-opener for the other global crisis–anthropogenic climate change–the slower one with even higher stakes.

Yes, the pandemic is indeed an eye-opener for climate change. Satellite images show a surprising effect of Covid-19 outbreak: reduction in air pollution and carbon/nitrogen emissions worldwide. The decrease in pollution is attributable to the economic slowdown caused by lockdown to contain transmission of the virus. We can now see how clean the air of Dhaka is, and how clear the water of the rivers is.

Covid-19 will not reverse the ravages of climate change, nor will it interrupt our progression towards a bleak future. Regardless, it is allowing us to see how ready the natural world is to reclaim the planet we have trashed, and how eagerly and swiftly it will rebound if we give it a chance. The pandemic is also teaching us that all is not lost. Perhaps lessons learned from this pandemic will be the beginning of a meaningful shift from the business-as-usual attitude towards climate change.

Some say that changes in the way humanity inhabits the planet are offsetting the benefits of the great scientific progress of recent decades. Do you agree?

I fully agree with them. Today, we are fixated on enjoying the present and refusing to account for the outcomes of our actions on tomorrow. We have a rather narrow view of the environment and an even narrower view of nature. Consequently, we have become more remote from the natural world outside our artificial environments.

We have made a mess of the environment; we are increasingly damaging our planet beyond repair. Yet, we do not realise that because of anthropogenic climate change, our wonderfully diverse planet will probably become uninhabitable before the end of this century. Or at the least, things will deteriorate to the extent that we could lose centuries of scientific, technological and economic progress in the next few decades.

Admittedly, the Covid-19 emergency has brought forth a renewed respect for science globally. Do you think this will lead to a renewed interest in studying science? What about Bangladesh?

Trying to solve the problems of epidemics and climate change without appealing to science would be foolish. I think the present crises will attract more people, particularly the younger generation, to study and do research in science and technology.

As a matter of fact, our present understanding of the global challenges of climate change, widespread environmental degradation and catastrophic pandemics has developed because scientists and students are collaborating internationally, conducting research worldwide and sharing data. Bangladeshi scientists should be part of this global collaboration and contribute towards a stronger and sustainable future. Researchers at Gonoshasthaya Kendra, Child Health Research Foundation and ICDDR,B, among other institutions, have already demonstrated that they can compete head-to-head with leading medical researchers of the world.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments