Rising tariffs may lead to a global recession

The impact of the seismic shift in the global economy caused by Trump's reciprocal tariffs is as immediate as it is personal. From factory floors in Vietnam to markets in Lagos and ports in Rotterdam, the consequences of rising trade barriers are being felt not just in numbers but in the daily realities of workers, producers, and consumers.

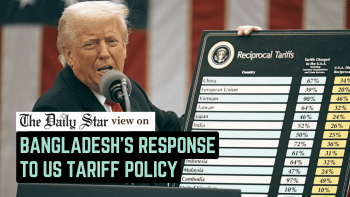

The resurgence of reciprocal tariffs—a form of economic retaliation that was once viewed as an outdated relic of 20th-century protectionism—are imposed in direct response to trade barriers enacted by another country, matching the restrictions "dollar for dollar" or "item for item." On April 2, 2025, President Trump announced a comprehensive 10 percent tariff on all exports to the US. China, referred to as the biggest target, was immediately impacted, while higher duties were also levied on European Union goods, reportedly affecting as much as $3 trillion worth of imported goods. Tariffs were also announced on Mexico and Canada, in part as a retaliatory move for fentanyl trafficking across the southern border—signalling the use of national security emergency powers to frame the trade agenda.

A new dimension has emerged in the US-China economic clash, with additional tariffs being placed on strategic sectors such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence chips. This is paired with renewed tension between the US and the EU, as Washington imposed 20 percent duties on European goods. With the new round of import tariffs on cars now in force, companies such as Volkswagen and BMW have seen their share prices plunge. Apparel supply chains have been heavily disrupted, affecting brands like Lululemon, Abercrombie & Fitch, and Gap.

Apple continues to produce key US-sold devices in factories across China, India, and Vietnam—further complicating its cost structure. NVIDIA, heavily reliant on China for AI chip supply, faces new hurdles.

In 2018, the United States introduced sweeping tariffs on Chinese steel, aluminium, and consumer goods, arguing that such measures were necessary to correct "unfair trade practices." In response, China imposed tariffs on American agricultural and industrial products. The logic was simple: if one country raises barriers, the other retaliates in kind. But the effects were anything but simple.

Across the world, producers and exporters began feeling the strain. From Argentine soybeans to German car parts, global supply chains were suddenly subjected to new layers of cost and uncertainty. Countries dependent on exporting raw materials or low-cost manufactured goods faced price volatility and declining demand. In others, increased import costs led to a spike in inflation, eroding household purchasing power. While some sectors—such as domestic steel and certain segments of manufacturing—saw modest gains in employment, others were undercut by higher production costs. For workers in industries dependent on global supply chains, the promise of tariff-driven revival has proven to be largely illusory.

South and Southeast Asian economies, particularly those dependent on low-skill manufacturing, have been the hardest hit. Vietnam, for instance, exports 46 percent of its GDP, with over 90 percent of that growth tied to trade. Any significant loss in global trade demand could be catastrophic. In this context, a 1-2 percent decline in Chinese GDP growth, currently forecast due to the tariffs, would have dramatic knock-on effects across Asia.

In the 1930s, the US Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act set off a global wave of retaliatory measures that many historians argue helped deepen the Great Depression. In the aftermath of World War II, the international community established a framework to avoid such cycles—first through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and later through the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Yet, decades of trade liberalisation have not resolved core tensions. As manufacturing jobs disappeared in developed economies and new industrial powers rose, political pressure mounted to protect domestic industries, often disregarding economic orthodoxy. The Trump-era tariffs marked a sharp break from the post-war consensus, but they also reflected a broader, global phenomenon: the return of economic nationalism.

While reciprocal tariffs have historically been associated with increased demand for the US dollar as a safe-haven currency, the dollar has weakened amid investor anxiety over policy unpredictability and a potential economic slowdown. Speculation that the Federal Reserve may cut interest rates to buffer against recessionary pressures has further weighed on the dollar. At the same time, the usual inflationary consequences of tariffs persist, pushing some central banks towards monetary tightening—despite global calls for policy caution.

De-dollarisation has gained traction, particularly among BRICS nations, which have explored alternative settlement systems and bilateral trade agreements in local currencies. The current trade shocks will likely push many countries to seek greater financial autonomy not only as a form of sovereignty but to hedge against future volatility in dollar-denominated trade.

In the private sector, the response to rising tariffs has been no less transformative. Multinational firms have begun to diversify supply chains, embracing what economists call the "China+1" strategy: maintaining Chinese operations while adding production bases in countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, and Mexico. Some companies have opted for nearshoring, bringing production closer to home. Others are exploring "friendshoring," sourcing goods only from politically aligned nations. These strategies, while aimed at minimising risk, represent a significant departure from the efficiency-driven logic that previously dominated global trade. They signal a world where resilience trumps cost-cutting—a world in which global integration no longer feels inevitable.

Financial indicators strongly suggest the onset of a mild global recession. Defensive stocks are outperforming cyclical ones, especially in sectors like consumer staples and utilities, while airline and carmaker stocks have plunged. The gap between cyclical and defensive stock performance is the widest since the Covid lockdowns in 2020. Global indices like the MSCI World have fallen sharply, with US and European markets experiencing similar declines. Investment banks have delayed IPOs, and analysts from institutions like JPMorgan Chase have raised recession forecasts to 60 percent.

Key sectors such as semiconductors, critical minerals, and pharmaceuticals are under close watch. In agriculture, tariffs have destabilised markets and increased the cost of essential equipment and fertilisers. In manufacturing, particularly in small and medium enterprises, increased input costs have pushed many to the brink. The complex web of intermediaries—suppliers, logistics companies, retailers—must now absorb and adapt to constant uncertainty.

As policymakers and institutions grapple with these challenges, a broader question looms: what kind of global economy do we want to build?

If tariffs and retaliations become the norm rather than the exception, the risk is not just slower growth or higher prices—it is the erosion of trust. Trust that trade can benefit more than a privileged few. Trust that rules and dialogue can replace confrontation. Trust that economic interdependence, carefully managed, can prevent conflict rather than provoke it. To navigate the changing trade system, global resilience must be redefined. It will require investments in digital infrastructure, diversification of trade partnerships, education systems that prepare citizens for technological change, and institutions capable of managing shared challenges.

Sarzah Yeasmin is a policy analyst who works on the intersections of education and development economics. She is an alumna of Harvard University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments