The many Bengals: Samatata, Bangalah, Subah-i-Bangalah

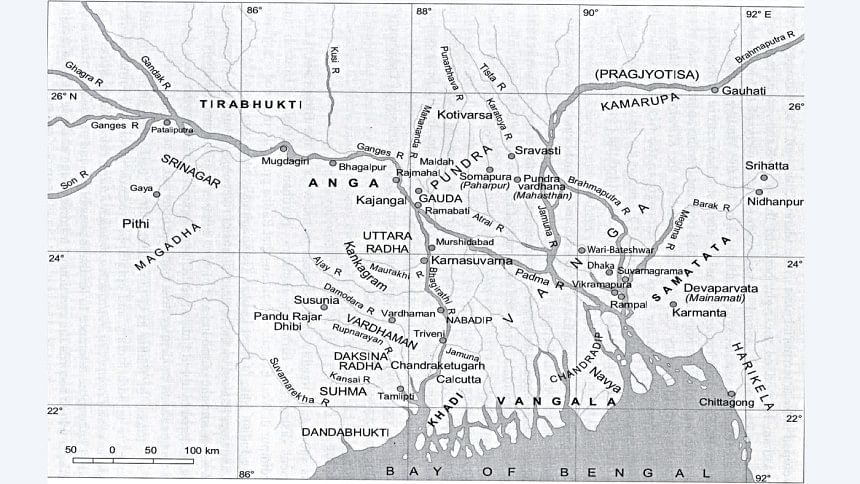

Historians usually approach Bengal's history from Gaur-Pandua in the west (i.e., Ilyas Shahi and Husain Shahi Bengal), but what of early Bengal? With a dynamic geography, there were multiple Bengals with oscillating contours. Anga was what is now eastern Bihar, Jharkhand, and northern West Bengal; Suhma, West Bengal and northwest Bangladesh; and Pundra, West Bengal and northern Bangladesh. There was no fixed core and no discernible capital.

I

Bengal became an aggregate of four distinct subregions, created by the prevalent hydrography: Pundravardhana (initially north Bengal, subsequently embracing a very large area of early Bengal); Radha or Rarh (largely to the west of the river Bhagirathi); Vanga (central deltaic Bengal, covering the Dhaka-Vikrampur-Faridpur area); and Samatata-Harikela (Bangladesh's southeasternmost part to the east of the Meghna, including Noakhali, Comilla, and Chittagong, and often parts of Tripura).

From the sixth century onward, these units crystallised into Vanga (lower Bengal between the Bhagirathi and the Padma-Meghna rivers); Varendra (present north Bengal and parts of Bangladesh); Samatata (formed of the trans-Meghna territories of the Comilla-Noakhali plain and the adjacent parts of hilly Tripura); and Harikela (the areas around Chittagong and the western part of coastal Arakan).

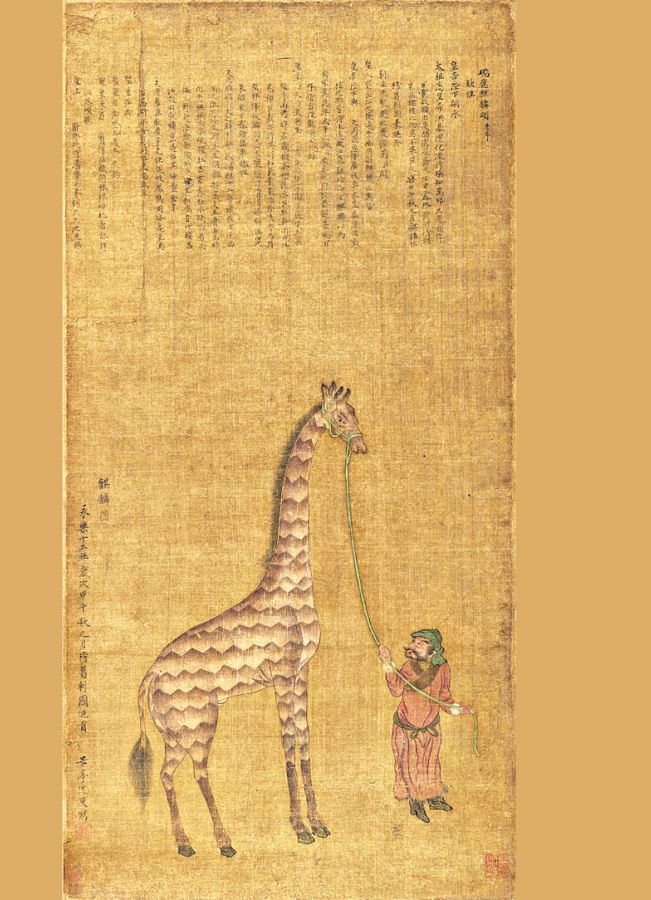

These units continued moving. By the twelfth century, the administrative unit of Pundravardhanabhukti, called Mahasthan or Great Place, linked the eastern Himalayan foothills with lower Bengal. Numerous waterways connected it to Kamrup, which housed the traditional land and fluvial routes into Burma, Yunnan, and China. Another unit on the far side of the Ganga-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta, Harikela, reinforced upstream-downstream links by reconfiguring boundaries and moving upward by the thirteenth century to include the landlocked polities of Srihatta and Tripura. This provided access to the Bay of Bengal. The sea would become very important to Bengal's economy.

The cultural turmoil resulting from these changes makes envisaging a heartland for Bengal difficult. Uncertainty came from upheavals caused by regional integration after the 'classical age' ended, from about the seventh century. This is when the contours of Bengal start taking shape.

Bengal's early political history centres around two polities: that of Sasanka (ca. 600–25, perhaps until 637), who achieved prominence by fighting Harsha of Kannauj and Bhaskarvarman of Kamrup; and that of the Palas—especially Dharmapala, Devapala, Mahendrapala, and Mahipala I—who are credited with transforming Bengal into an imperial power. Sasanka's kingdom was based on Gauda (not to be confused with Gaur in Lakhnauti), with its core at Karnasuvarna in western Bengal. Gauda's territorial extent is unclear but seems to have stretched westward to Magadh and parts of Bihar, southward to Odisha, and eastward to Kamrup. The Pala polity, however, is like an imperial mandala without a clear core. It was also a cashless and coinless economy.

II

From the thirteenth century onwards, with Muslim rule, a process of territorial consolidation occurred, and some changes ensued. Southeast Bengal became 'Bangalah'—the 'Bengala' of the Portuguese accounts echoes this. It was Bangalah, not the west, that was economically and culturally advanced. Lakhnauti referenced western Bengal. They were two distinct polities, integrated only in the fourteenth century into what we call medieval Bengal. Under the Ilyas Shahis, although the capital was in Pandua in the west, more mint towns were found in the southeast. Under the later Ilyas Shahis (1437–87), as many as 20 mints existed. Of these, Fathabad was the sultanate's most significant mint, with a prodigious silver output. Silver came in by sea from Arakan and Pegu and subsequently overland from the Shan states between Upper Burma and Yunnan.

III

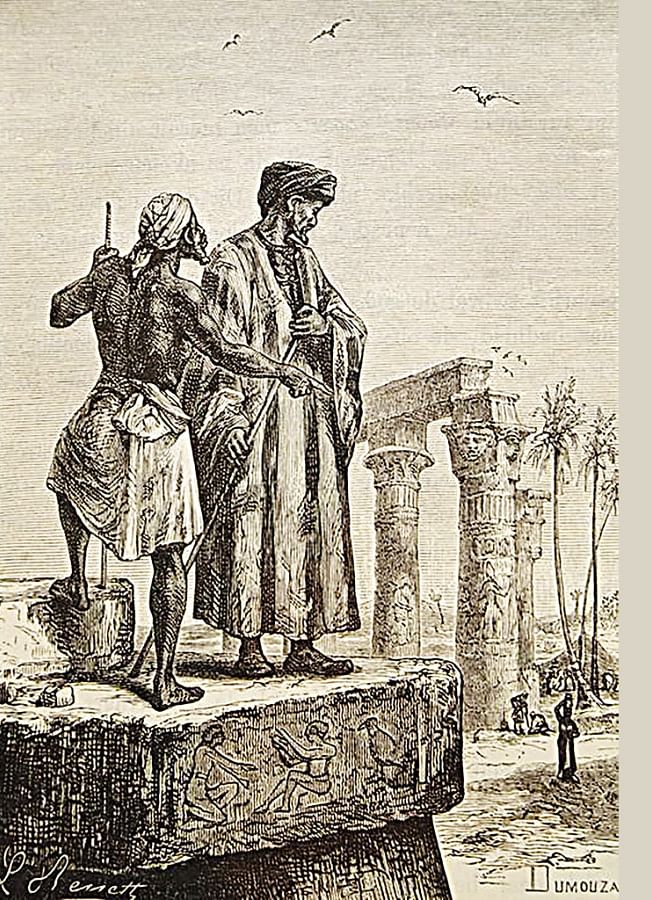

The Bengal coast's distinctiveness lies in its funnel-like shape—the only asamudrahimacala region (from the mountains to the sea) in land-locked northern South Asia—and it was accordingly privileged in foreign notices. On 9 July 1346, Ibn Battutah came into Bengal through Chittagong—a city filled with food, but it smelled bad, and yet it was 'a hell full of good things'. Everything was cheap, including slaves. He bought 'an extremely beautiful' slave girl, and a friend bought a young slave boy for two gold dinars. He came to Sonargaon on 14 August 1346. There he boarded a Chinese junk bound for Java.

There are several notices on these two port-cities: Chittagong and Sonargaon. Fei Xin's Hsing-ch'a-sheng-lan (The Overall Survey of the Star Raft, ca. 1436) saw Chittagong as Bengal's gateway and only seaport, but Sonargaon (the 'Sonargawan' of Fra Mauro's 1450 world map)—and not Chittagong—was the political centre and maritime hub:

'This country has a sea-port on a bay called Ch'a-ti-chiang [Chittagong]; here certain duties are collected…After going sixteen stages (we) reached So-na-erh-chiang [Sonargaon], which is a walled place with tanks, streets, bazaars, and which carries on a business in all kinds of goods. (Here) servants of the King met (us) with elephants and horses. Going thence twenty stages (we) came to Pan-tu-wa [Pandua], which is the place of residence of the ruler.'

Ma Huan's Ying-Yai Sheng-Lan (The Overall Survey of The Ocean's Shores, 1433) noted:

'Travelling by sea from the country of Su-men-ta-la (Acheh)…the (Nicobars) are sighted, (whence) going north-westward for twenty li one arrives at Chih-ti-chiang. (Here) one changes to a small boat, and after going five hundred odd li, one comes to So-na-erh-chiang, whence one reaches the capital. It has walls and suburbs; the king's palace, and the large and small palaces of the nobility and temples, are all in the city. They are Musulmans.'

Ming China's expansion in the fifteenth century destroyed upland polities—Tai, Ahom, Mong, and Meng—leading to substantial human migration into the southeast. Nicolò de' Conti's itinerary (ca. 1420s–30s) reveals this dynamic relationship between places:

'Travelling many dayes journey by land, and by sea, he entred at the mouth of the Ryver Gangey, and sayled fifteene dayes up the river, and came unto a Citie named Cernomen [Sonargaon], very noble and plentiful…Going from hence uppe the ryver three moneths, leaving behinde him foure famous Cities, he came to a goodlye famous Citie named Maarazia [?Varanasi], where there is great plenty of the trees called Alloes, and plentie of golde, and silvr, Pearles, and precious stones. And going from hence he directed hys waye unto the mountaines of the Orient, for to have Carbuncles, and travelling thirteene dayes, he returned firste to Cermon and afterwardes unto Buffetanya [Vardhamānapura or Chittagong]. And after that, sayling a wholemoneth by sea, he came unto the entring of the river Nican [Arakan], and sayling uppon it sixe dayes, he came unto the Citie also name Nican, and he went from thence seaventeene dayes journey throughe deserte mountaynes, and plaine countrey, the fifteene days of which the people of that countrey cal Clava, and sayling up this river a month, he came unto a famous great Citie called Ava, being 15 miles in compasse.'

In 1585, Ralph Fitch saw a region called 'Bengala', with 'Porto Grande' lying in the Tripura-Chittagong belt. Evidently, Sonargaon was no longer the maritime hub:

'From Satagam I travelled by the Countrie of the King of Tippara or Porto Grande, with whom the Mogores or Mogen [Arakanese] have almost continuall warres. The Mogen, which be of the Kingdome of Recon [Arakan] and Rame [Ramu], be stronger then the King of Tippara, so that Chatigan or Porto Grande is oftentimes under the King of Recon....From Chatigan in Bengala, I came to Bacola [Bakla]…From Bacola I went to Serrepore [Sripur], which standeth upon the River Ganges, the King is called Chondery [Chand Rai]…Sinnergan [Sonargaon] is a Towne sixe leagues from Serrepore…I went from Serrepore the eight and twentieth of November, 1586 for Pegu in a small Ship or Foist of one Albert Caravallos, and so passing downe Ganges, and passing by the Hand of Sundiva, Porto Grande, or the Countrie of Tippera, the Kingdome of Recon and Mogen, leaving them on our left side…: our course was South and by East, which brought us to the Barre of Negrais to Pegu…From Bengala to Pegu is ninety leagues.'

IV

These accounts indicate not only Bangalah's connections but also its bountiful landscape. Ibn Battuta found a picturesque land, a wealth of green and blue in every possible shade:

'we sailed down the river (Meghna?) for fifteen days passing through villages and orchards as though we were going through a mart. On its banks there are water-wheels, gardens and villages to right and left like those of the Nile in Egypt. Thus, while the abundance of the necessaries of life and its soothing scenery made it a very attractive country to live in, the foggy atmosphere (cloudy and gloomy weather), aided by vapour… particularly the steaming inhalation from the creeks and inlets during the summer, was… oppressive.'

The merchant-mariner Thomas Bowrey called seventeenth-century Bengal 'one of the largest and most Potent Kingdomes of Hindostan… blessed with many fine Rivers that issue out into the sea of Gulph of Bengala vizt. below Point Palmirs… and the Arackan Shore… some of which are navigable both for great and small ships… This Kingdome is now become the most famous and Flourishinge'. In the 1680s, per William Hedges, Bengal was still 'ye best flower in ye Company's Garden and all India'.

What changed subsequently?

V

At a time when the west-east fluvial shifts saw much economic activity (the port towns of Bakla, Sripur, Loricul, Katrabuh, and Sandwip were drawn into Portuguese networks by the early sixteenth century) and agricultural yields rose, southeast Bengal was hitched to the Mughal Empire. Six new rivers and their channels linked it to the western delta's rivers, and these facilitated access to Delhi. This connect killed off its economic vitality. Business was hampered because goods now went to the west through the new channels. Trade by the Meghna–Brahmaputra channel to the northeast, Ava, and Yunnan was no longer a viable option due to political uncertainties. Instability in Burma from the sixteenth century meant that routes to China through Upper Burma were risky. Soon after, the sea route to Arakan fell into disuse.

In a sub-global context, as this world faced a crisis, traditional players went, supplanted by new state forms. In a global context, the Portuguese conquest of Melaka in 1511 transformed it from a regional entrepôt to a world emporium in the sixteenth-century age of commerce. This reoriented or destroyed existing networks and caused the decay of previously robust polities. There was warfare in Tripura, Bhulua, Mrauk U Arakan, Toungoo and Mon Burma, Lan Na, and Ayutthaya. Interior Sukothai ceded way to maritime Ayutthaya. Massive shifts in human population occurred. Burma was particularly unstable until unified by the Toungoos from 1510. Ava was destroyed in 1527 and Mon Pegu was defeated by the first Toungoo state in the 1530s. Husain Shahi Bengal ended in 1538. The succeeding Sur dynasty revived uttarapatha as Badshahi Sarak (later called Grand Trunk Road) and linked Sonargaon to Delhi and beyond. Then the Mughals came and, by the early seventeenth century, started their push into southeast Bengal.

VI

Economic expansion, the use of firearms, and provincial reorganisation had rendered post-sixteenth-century southeast Bengal stable, but this trend reversed in the seventeenth century. Southeast Bengal entered into an unequal relationship with the Mughals as a raw material and cash crop (rice, raw cotton, sugar, oilseeds) supplier for the empire. This accounted for its still high revenue assessment at 50 crore dams, but the vibrant port towns of the southeast now became mere providers of agricultural produce.

Yet, while trade declined and people moved elsewhere, the sixteenth-to-eighteenth-century fluvial shifts rendered the western delta 'moribund' and the southeastern delta 'active'. The active delta boosted the vital agricultural base. Production zoomed. But the shifts also flooded villages and caused human displacement. Southeast Bengal's fragmented coastline, with its rivers, creeks, and inlets, saw persistent magh (Portuguese-Arakanese slavers) raids. The Mughals could not combat this menace. Shihabuddin Talish wrote that a hundred boats of the Mughal Bengal fleet fled if they saw even four of the enemy's boats. The agriculturally productive southeast became a pirate-infested, slave-raided area.

Contemporaries have left us their impression of the raided areas. The English East India Company official Streynsham Master wrote on 7 September 1676: 'This morning wee came faire by the Arracan shore… and came to an anchor at the mouth of the River near the Ile of Coxes…' (Sagor, south of Kolkata), and added on September 8: 'This day we passed by the River which goes to Chittygom and Dacca, which the English call the River of Rogues, by reason the Arracaners used to come out there to Rob…'.

Bowrey, Master's contemporary in Bengal, noted: 'Many Isles there be in the mouth of the Ganges, not inhabited more than with wild beasts… the Natives much dreadinge to dwell there, being timorous of the Arrackaners with their Gylars who many times have come through the Rivers and carried away captive many poor families of the Orixa folks'.

Yet another contemporary, François Bernier, wrote: 'They scoured the neighbouring seas in light galleys, called galleasses, entered the numerous arms and branches of the Ganges, ravaged the islands of Lower Bengal, and often penetrating forty or fifty leagues up the country, surprised and carried away the entire population of villages on market days… (or) a marriage. The intruders made slaves of their unhappy captives.' He added: 'It is owing to these repeated depredations that we see so many fine islands at the mouth of the Ganges, formerly thickly peopled, now entirely deserted by human beings, and become the desolate lairs of tigers and other wild beasts.'

These remarks show the raids had now penetrated into the western delta.

Overall, an expanding population in Bengal from the mid-sixteenth century resulted in population pressure and a resource crunch in the seventeenth century, accelerated competition for resources, and engendered chronic warfare. Demographic trends explain some long-term processes: population rise; vibrant trade; incipient commercialisation; new styles of warfare, i.e., a changeover from cavalry-based warfare to gun-equipped troop warfare; disease such as smallpox (Ahom Assam: 1574, 1637, 1768; Manipur: 1520, 1531, 1541, 1581, 1651, 1672, 1685, 1699, 1720, 1744); and frequent famines (a particularly severe one occurred in the 1660s in the southeast). Maritime decay and commercial decline triggered the seventeenth-century crisis, leading to famine, disease, and slavery at a time when the circuits of international trade were enmeshing this world.

Southeastern Bengal underwent a triple squeeze: an ecological squeeze from its west, an expanding frontier squeeze from Arakan, and a renewed economic squeeze from Mughal Bengal at a time when the old order was in disarray. Population decline goes a long way in explaining this seventeenth-century crisis. James Rennell's 1780 map of the Bengal delta marked it as a 'Country depopulated by Muggs' and showed several forts around Bakla that were built to repel magh attacks. Warren Hastings's survey of five villages in the Chittagong region from 1768 to 1772 showed birth rates in drastic decline, indicating the insecurity and terror caused by magh raids. After this, the focus of history-writing shifts to western Bengal and, although most of the southeast became part of British Bengal, it, with the exception of Dhaka, enters our attention only in the late nineteenth–early twentieth centuries.

Rila Mukherjee is a retired Professor in History, University of Hyderabad, India.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments