How Bangladesh gained global legitimacy

When Bangladesh defeated Pakistan on 16 December 1971, one could be forgiven for assuming that the international community automatically recognised Bangladesh's independence. However, my current research into how Western states responded reveals that this assumption could not be further from the truth.

A brief history of recognition practices

The fact that Bangladesh gained international recognition at all is remarkable. In modern times, it is rare for a secessionist state to achieve international legitimacy without the assent of the home state. In fact, it has happened only twice in the past three hundred years: Belgium, which began its secessionist movement in 1830, waited nine years for recognition, and Ireland, which began its independence war from the UK in 1919 but was not recognised as a republic until 1949. Generally, unilateral acts of secession without support from the home state result in international silence if not explicit condemnation.

Why is it so difficult for secessionist movements to gain international recognition?

The main reason is states fear setting a precedent for other disgruntled minority groups within their midst to declare independence. Globally, states are comprised of multi-ethnic populations, some of which have made claims for secession. From Quebec in Canada to Transnistria in Moldova, such calls for independence undermine state authority. It is therefore in the interests of governments to dissuade independence movements as they pose an existential threat.

There are other, more practical, reasons to deny statehood to secessionist groups. Economic factors loom large. As was the case with East Timor, home states can use the presence of natural resources as a bargaining chip to secure international support. The international community oftentimes expresses concern that supporting one secessionist group could trigger regional conflicts and undo accepted international borders, as is the case with Kurdistan.

Legally, the issue of international recognition of breakaway states is unclear. The United Nations (UN) is often lauded for spearheading decolonisation. This is true. But what is also true is that the UN applies a "decolonisation only once" principle. Comprised of (and funded by) states, the UN has a vested interest in protecting the existing territorial borders of its members. Furthermore, in international law there is no agreed-upon mechanism under which state recognition must occur, nor is there any widely accepted legal definition of statehood.

In short, the act of state recognition is a political behaviour rather than an impartial legal decision. The decision if and when to recognise a newly formed state is driven primarily by self-interest and cost-benefit analysis. The lofty ideals of freedom and self-determination rarely rate a mention.

Despite its ambiguous process, the decision to recognise a secessionist state does matter. It has been said that without international recognition, a declaration of independence by a breakaway territory is like one hand clapping: it is pointless. International recognition has the power to turn an isolated, emerging nation into a fully-fledged member of the international community and all the benefits that it entails: including access to trade agreements, establishment of diplomatic missions, freedom of movement across international borders, and access to membership of global and regional organisations.

Timeline of recognition

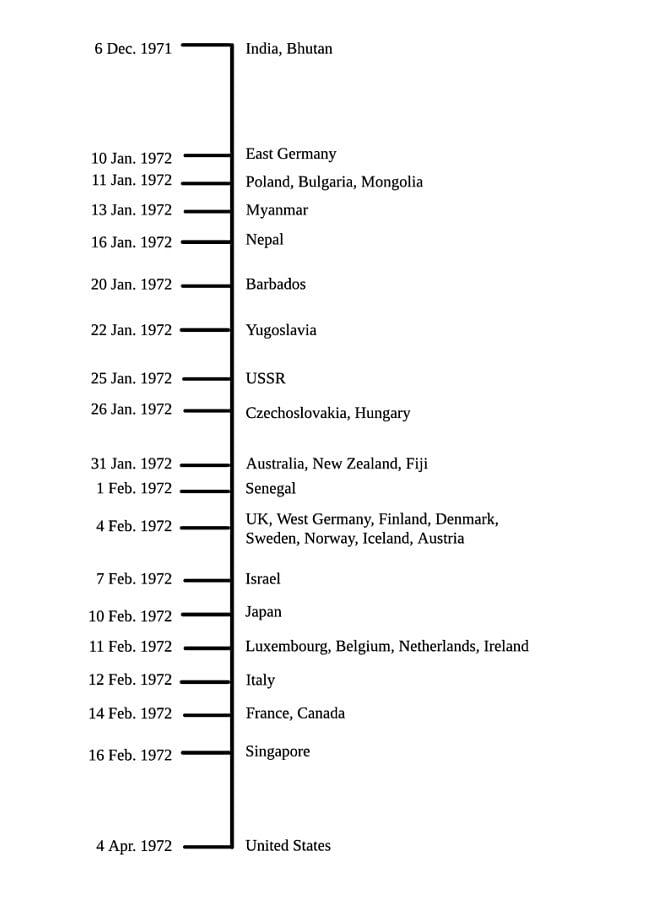

As is well-known, India and its ally Bhutan recognised Bangladesh before the Liberation War ended. But for the rest of the international community, recognition was not considered a viable option until Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was released from Pakistani custody. The next bloc of countries to recognise Bangladesh came from communist Europe: East Germany, Poland and Bulgaria. Australian diplomatic cables state that these communist states were used as "Soviet pathfinders to recognition". That is, Moscow ordered these states to recognise Bangladesh early to assess the reaction of Pakistan.

Once the USSR was satisfied that Pakistan's threats of retaliation were hollow, it recognised Bangladesh on 25 January, followed the next day by Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Diplomatic cables document why Communist Europe was keen to recognise Bangladesh early. Legitimising the young nation offered the communists a "propaganda win" by "beating the west", and marginalising Maoism in the region.

On the surface, this timeline suggests that the western world was slow to recognise Bangladesh. However, Australian archival evidence indicates a more complicated story.

It is true that the United States, under the leadership of Richard Nixon, delayed recognition of Bangladesh until April, if only to punish India for a perceived lack of gratitude for American aid. At the same time, the Nixon Administration was planning its historic visit to the People's Republic of China in February 1972 to normalise relations between the two adversaries. Pakistan was a crucial intermediary in this process and the US was loth to insult its ally so close to the Beijing trip.

The other great power, the UK, was torn on multiple fronts: it feared that recognising Bangladesh may trigger Pakistan to withdraw from the Commonwealth yet failure to recognise Bangladesh could jeopardise access to a profitable trading partner. With memories of British imperialism still fresh, the UK government was reluctant to intervene in its former colony. Moreover, in 1971 the UK was focused on gaining admission to the European Community (EC) and had famously withdrawn its troops "east of Suez" in 1971.

With the US preoccupied and the UK uncertain how to act, a vacuum was left for so-called middle powers such as Australia to fill the void.

Australia leading the West

Although Australia formally recognised Bangladesh on 31 January—as the first Western nation to do so, along with allies New Zealand and Fiji—Australian diplomats had been actively advocating for Bangladesh's recognition behind the scenes since 24 December, eight days after the ceasefire.

Even before the war commenced on 25 March 1971, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) began preparing staff for the disintegration of Pakistan. Then, on 24 April 1971, Vice President of the Bangladesh government-in-exile, Syed Nazrul Islam, wrote to the Australian government. In his letter, Nazrul Islam attached the Bangladeshi Proclamation of Independence and asserted, "the people of Bangladesh, by their heroism, bravery and revolutionary fervour have established effective control over the territories of Bangladesh". The Australian government did not respond to this letter as it would have been deemed inappropriate to communicate directly with the government-in-exile. However, unofficially, as early as June 1971 the Australian Prime Minister William McMahon lobbied for the release of Mujib from Pakistani custody as a first step to a political solution to the conflict and a step towards autonomy.

By December 1971, it was clear to Australians that a ceasefire was imminent, and they needed to determine their allegiance: to recognise Bangladesh early and risk a severance of diplomatic relations with Pakistan, or to acquiesce to Pakistani demands and refrain from formal recognition of Bangladesh.

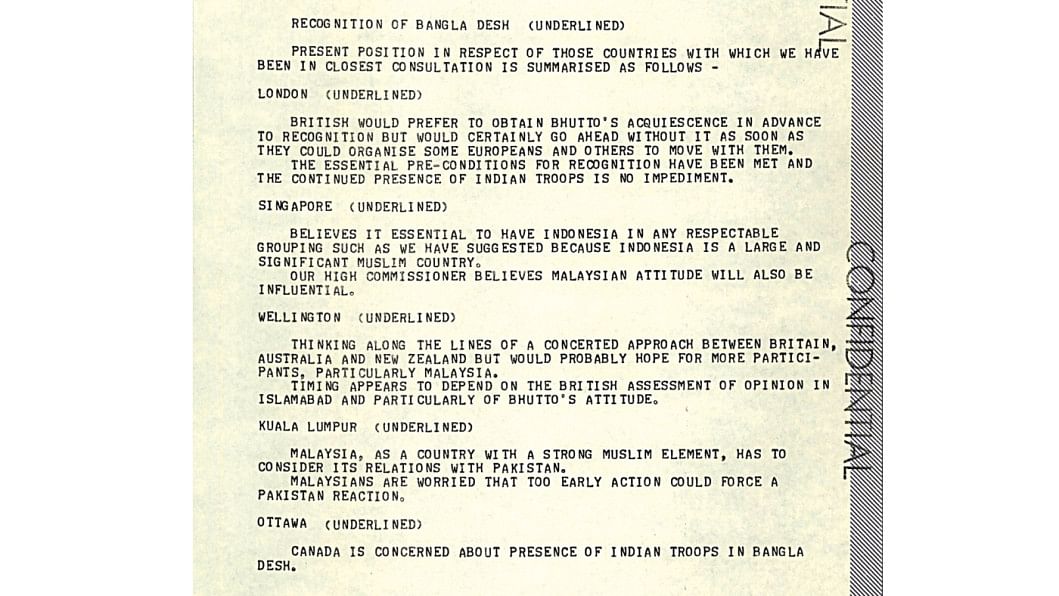

For many western and Asian nations, the second option was most appealing as it offered the least risk in the short-term. Figure 2 shows the positions of the UK, Singapore, New Zealand, Malaysia and Canada. All Commonwealth countries shared the same characteristic of risk-aversion, even if that meant stymieing the possibility of Bangladesh to stabilise and prosper in the post-Liberation War period.

The Australian position was markedly different from its western and Asian allies. Arguably, Australian diplomats had been preparing for an independent Bangladesh throughout 1971, even if they never publicly declared it. With few exceptions, the Australian government sided with Bangladesh's aspirations for statehood. On 11 December 1971, Australian High Commissioner to India, Patrick Shaw, cabled to DFA:

As for your fears that "premature recognition would have adverse effects on Australian relations in Islamabad", it is more important to consider Australian relations with Dhaka and with New Delhi.

Leading Australian diplomat Sir James Plimsoll concurred, stating "I agree with Shaw too that we should not create obstacles to our establishing some relationship with Bangladesh before too long". These opinions informed the position of the DFA, which urged the Australian Foreign Minister Nigel Bowen on 13 December: "Australia should move to recognise Bangladesh as soon as practicable after the installation of a new government in Dhaka".

With the ceasefire on 16 December, Australian deliberations shifted from whether to how to recognise Bangladesh. The Australian government employed multilateral diplomacy to persuade like-minded nations to join Australia and recognise Bangladeshi independence quickly and as a bloc. The reasons for wanting to recognise Bangladesh collectively were based on practical advantages. Oftentimes, acts of contemporaneous state recognition create momentum and stimulate other nations to follow suit. When a group of nations act simultaneously, it bestows greater legitimacy on the country being recognised.

From 24 December, Australian diplomats across the globe were instructed by the DFA to "sound out" western and Asian governments on their willingness to recognise Bangladesh. While the response was positive, none was ready to act.

After the release of Mujib from Pakistani custody on 8 January 1972 and his arrival in Dhaka on 10 January, the Australian government commenced a second round of negotiations. From 11 to 17 January, Australian diplomats sought to persuade other governments to recognise collectively on 19 January. Although Bangladesh had demonstrated it fulfilled all criteria for recognition, some states were still hesitant. Typically, each state that Australia approached may have supported in principle recognition of Bangladesh yet opposed to acting early for fear of retaliation from Pakistan or offending Muslims in the Middle East. Indeed, in January Saudi Arabia warned the international community that recognition of Bangladesh would be viewed as a "hostile act", a threat that spooked Western Europe.

Like its December effort, Australia's endeavour in mid-January to secure a coalition to recognise Bangladesh was unsuccessful. But the Australian government remained undeterred and continued negotiations through January. Socialist Yugoslavia proved an unlikely ally, and in the end it recognised Bangladesh on 22 January, before Australia. In the third round of negotiations, Australia continued to lobby south-east Asian nations, Japan, Canada and western European states. Australian diplomats in Latin America contacted their counterparts in Argentina and Mexico, although these approaches failed completely.

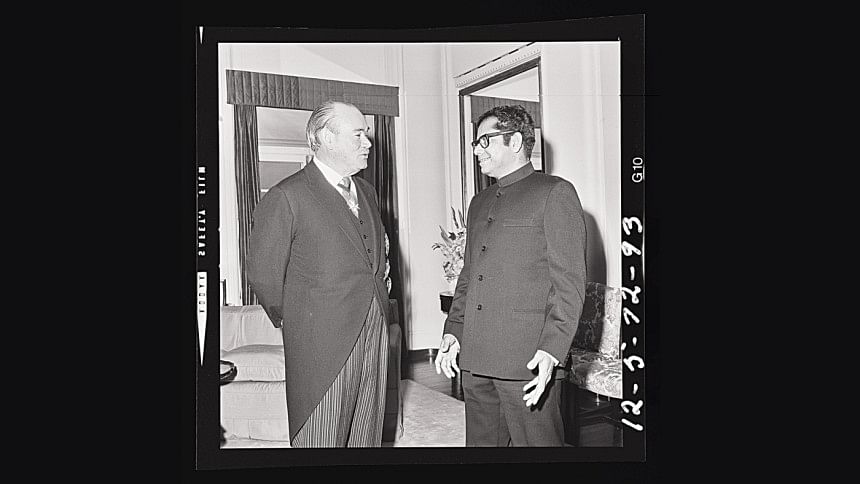

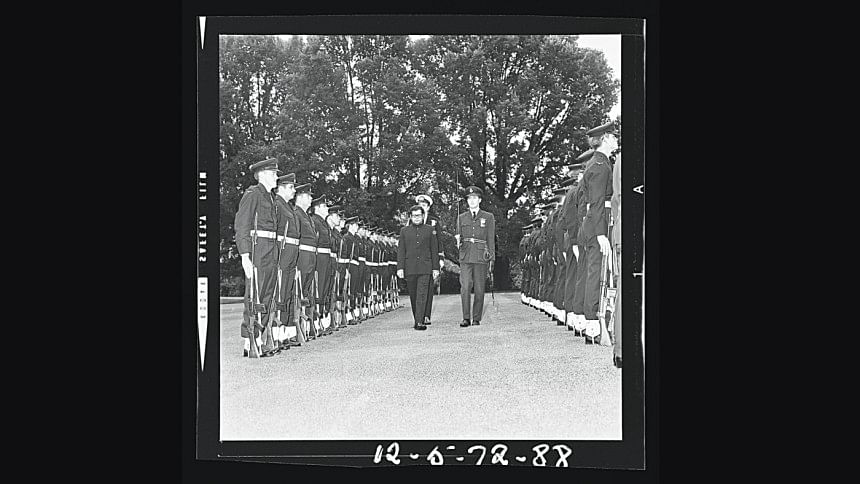

In the final week of January, Western European governments agreed they would recognise Bangladesh at some point. But by now, the Australian government was unwilling to wait, having had their plans thwarted twice within four weeks. In the end, Australia recognised Bangladesh on 31 January, one week after Australian Cabinet approval and five weeks since Australian diplomats began mobilising western support for recognition. . On 14 April 1972, the Australian government accredited Hossain Ali as Bangladesh's High Commissioner—the first OECD country to open a diplomatic mission. See Figures 3 and 4.

Australia's position on recognition of Bangladesh was unusual in that it was not entirely focused on self-interest, such as trade implications. Australian diplomats believed that early recognition was important to "help Bangladesh get on its feet" and show "that the communists are not its only friends". Numerous Australian diplomats argued that early recognition was vital to cement the leadership of Mujib and foster moderate politics. Peculiarly, Australian diplomats viewed Bangladesh as a Southeast Asian nation. While geographically inaccurate, the fact that they situated Bangladesh within Australia's neighbourhood reveals an imagined closeness between the two nations.

That Australia was the first Western nation to recognise Bangladesh, and that its diplomats lobbied both Western and Asian governments to do the same, represents a rare moment in Australian foreign policy that was independent of the UK. It also demonstrates the potential of middle-power diplomacy to offset American obstinance, offering a pathway to help Bangladesh realise its aspirations of independence.

Rachel Stevens is a Lecturer in History at the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Catholic University in Melbourne.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments