New draft social media, OTT regulation: Why we should be worried

The Digital Security Act (DSA) has been proven repeatedly to criminalise the online activity of citizens, using flimsy criteria.

But there is a piece of new draft legislation that aims to do more. Instead of prosecuting citizens, this one intends to put social media platforms and tech companies on the docket for the online activity of their users.

In essence, this means that instead of targeting individual users, companies and publishers can be held liable, who in turn will then be compelled to censor their own users – or so experts fear.

"The Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission Regulation for Digital, Social Media and OTT Platforms", which was released by the Commission early last month, has since then sent right organisations into a flurry.

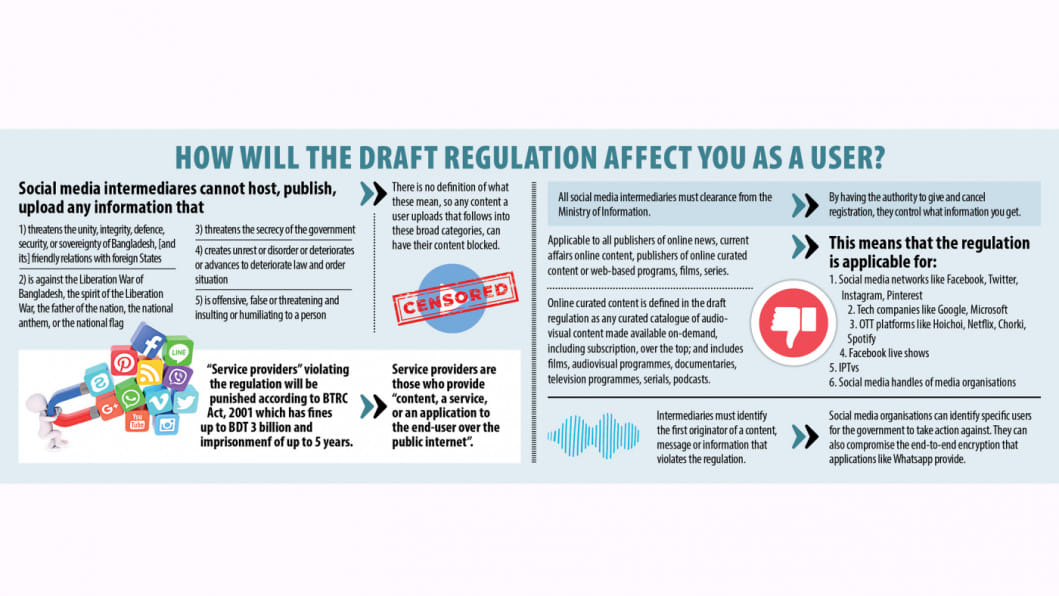

The regulation prohibits some of the things that are outlawed under the DSA, but this time, instead of end users, service providers will be held culpable.

Similar to the DSA, this regulation prohibits any content that "creates unrest or disorder or deteriorates or advances to deteriorate law and order situation" or "is offensive, false or threatening and insulting or humiliating to a person".

It also forbids content that threatens the "unity, integrity, defence, security, or sovereignty of Bangladesh, [and its] friendly relations with foreign states", content that goes against the Liberation War of Bangladesh, the spirit of the Liberation War, the father of the nation, the national anthem or the national flag, or anything that "threatens the secrecy of the government".

According to the regulation, all social media intermediaries will be required to have a resident complaint officer, a compliance officer to ensure due diligence, and an agent to liaison with law enforcement agencies and the BTRC.

The compliance officer will be tasked with making sure that the conditions stated in the regulation are upheld. Should they fail to comply with those standards, service providers will be punished according to Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulation Act, 2001 which has fines up to Tk 300 crore and imprisonment of up to 5 years.

The draft regulation defines service providers as those who provide "content, a service, or an application to the end user over the public internet". This lumps together social media platforms, web publishers, and on-demand, over-the-top services.

This hanging noose has sent global tech companies and rights bodies into a state of panic. Global Network Initiative (GNI), a collective whose members include Meta, Microsoft, Uber, Zoom, Telenor Group, Yahoo, Google, Nokia, Vodafone, Verizon, Human Rights Watch, Wikimedia, Committee to Protect Journalists and others, sent a letter to BTRC expressing extreme alarm.

"These significant penalties paired with stringent obligations will put undue pressure on intermediaries to restrict content or share user data," said GNI in a letter.

Transparency International, Bangladesh (TIB) added, in their own submission to BTRC, by saying that this "creates disproportionately high enforcement risks against companies."

"There is no requirement for the authorities to take a graded and proportioned approach, which, from a law enforcement perspective, means that the companies will constantly have to run the risk of being subjected to disproportionately high penalties," commented TIB.

Essentially, what they are saying is – can a platform hosting child pornography be given the same harsh penalties as a platform for hosting a status "hurting religious sentiment" or threatening Bangladesh's "friendly relations with foreign states"?

Other rights bodies have pointed out that there is no actual way for anybody to determine what constitutes a violation.

"Many of the terms regarding prohibited online content are vague. This creates a risk of being interpreted differently by different people, and uncertainty in terms of those creating, publishing, or sharing digital or social media content not knowing whether or not they are liable for breaches of the Regulation," said Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST) in their submission to the BTRC.

BLAST further explained, "For example, social media intermediaries are required to block content that is 'false or threatening and insulting or humiliating to a person'. Content that goes against 'decency, morality, social acceptance, social values, against national culture' is also prohibited – but these terms have no universal definitions, each person will have a different view."

Sunamganj youth Jhumon Das was arrested in March last year, under the Digital Security Act, for posting a status about Hefajat-e-Islam leader Mamunul Haque. His case stated that he hurt religious sentiment by commenting on the Islamic leader.

Subsequently, however, Haque was arrested in a widely publicised raid in a hotel, where he was found with his second wife. He was prosecuted in 17 separate cases for inciting communal violence.

All forms of media, including social media, were slathered with coverage and critiques of Haque; Jhumon was arrested for precisely this and his act was classified as "hurting religious sentiment".

"We have seen interpretation of the abovementioned grounds arbitrarily to suit motivated objectives over the years. There is no standard of reasonableness that is ascribed when assessing whether an action tantamount to a severe and genuine violation of these grounds," opined TIB in their letter.

In addition to threatening platforms and companies with prosecution, the draft regulation empowers the BTRC with the ability to direct service providers to remove or block content – and the providers must comply.

GNI said that this will make it difficult for intermediaries to respect their users' rights to freedom of expression and privacy.

"The penalty for non-compliance with a removal order is disproportionate and unacceptable," said TIB in its letter, adding that this takes away the agency of the service provider to make sure that removal requests are justified.

Meanwhile, the Internet Society said in a policy brief, the scope of content takedown laid out in the draft regulation is overly broad and loosely defined, which "risks making a substantial portion of global knowledge inaccessible to internet users in Bangladesh."

"To police a broad swath of content on their platform, intermediaries will most likely need to rely on automated systems, which are notorious for their inability to meaningfully distinguish between legal and illegal information. For instance, filters designed to target the word 'breast' have previously blocked content about breast cancer," said the Society.

Experts point out that the regulation does not distinguish between different types and sizes of service providers and intermediaries, as a result, putting the same rigid trappings on a small vlogging channel as a large tech company, such as Meta.

"It is important to recognise that companies such as internet service providers, search engines or web infrastructure companies are less well positioned than social media companies to address concerns about particular online content and conduct, and if subject to the same liability and legal requirements, may be forced to disable access to entire internet-based platforms, services, web pages," said GNI.

The trappings do not end. All service providers must register and get clearance from the Ministry of Information. TIB called this "unwarranted".

"The right of BTRC to cancel, suspend or revoke registration certificates creates substantial business continuity risks for non-resident service providers, which will serve as a significant deterrent for many companies to enter the Bangladesh market, or offer services to local consumers," said TIB.

With its sweeping penalties and broad definitions, the regulation achieves what the DSA could not – instead of repressing freedom of expression of individual users, it uses mass-control techniques for highest possible impact.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments