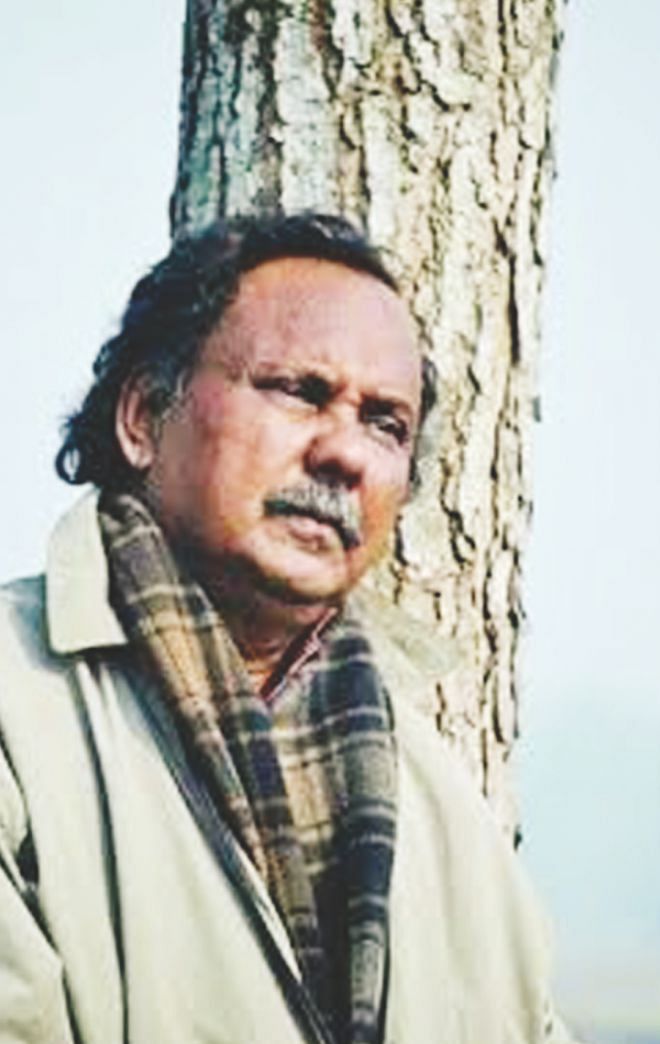

Khondakar Ashraf Hossain

WHILE reminiscing about a late professor, Professor Dr. Fakrul Alam would often quote this famous line from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales: “And gladly would he learn and gladly teach”. Very impressive, this line, I think, also encapsulates the quintessential characteristics of Professor Dr. Khondakar Ashraf Hossain, who breathed his last on June 16, 2013.

Dr. Fakrul Alam no doubt personifies the truth of the quotation. But my first chance encounter with this line set me on an unfailing quest to explore its semblance in others as well. I know I am the most inattentive of students, and yet this silent quest kept me vigilant all through a class.

My encounter with Professor Dr. Khondakar Ashraf Hossain lived up to my expectations. The air of confidence with which he kept teaching us set me to ruminating inside the class and outside. I recall how often I laughed and talked to myself even after the class, erecting in the mind a secluded palace of my own to study, envisage and materialize my dreams.

I remember an occasion when I asked, “What is your grandfather?” to his grandson and granddaughter, Rubab and Miti, whom I was tutoring years back. They were twins, and like most other twins they believed in fierce competition. Vying to introduce him to me, Rubab said, “He writes poetry” while Miti retorted, “No. He teaches at a university”. Neither was incorrect. I knew him very well, yet I posed the question only to see what the little ones do in such a situation. Now that I studied many years under his tutelage and that he is no more among us, I understand that a wondrous combination of both qualities made him such a personable teacher in the department.

While teaching us poetry, most of the time he would translate some esoteric lines from such difficult poets as Eliot. Might we have not needed a Bengali translation of an English poet, but his poetic ammunition was remarkable enough to electrify, entrance and embolden our fledgling, inchoate literary psyche in our academic trajectory. A savant in different languages like English, German, Bangla etc. including most of the dialects of Bangla, he even translated some of Eliot's poems into a Dhaka dialect.

A poet himself, he well understood the chasm between theory and practice and more often than not tried bridging the gaps. While it is usually expected of the teachers in an English department to know how a theme and a style coalesce in literary work to produce something of a novelty, for him it was more of an intuition than mere knowledge. Precisely for the intuitive quality, he could bring in the 'magic moment' in class, which is a perennial Holy Grail for teachers, but for some it is nothing more than an abortive endeavor and every once in a while ends in complete fiasco.

Apart from teaching, he launched several literary and cultural initiatives, Krishnochura being the quintessence of his efforts. After an incident in the department two or three years back, the Chair had to suspend many of the programs active in those days. With those programs seeing their better days, students had to go to the TSC to enroll in cultural programs. But it was he who wanted a change, and no doubt he made a splash!

While teaching us Eliot's The Wasteland, quite poetically, he would often say that the larger the crowd is, the lonelier a person feels—a European conviction underlying his PhD dissertation, Modernism and Beyond: Western Influences on Bangladeshi Poetry, which he defended under the tutelage of Dr. Syed Manzoorul Islam, another doyen and celebrated writer in the department. No doubt, modernism and postmodernism, the two fields falling within his purview of literary and critical interest, must have made him construe life in that light. But inspirational, it left an indelible imprint on my mind. Later I myself vented my pent-up emotion about the feeling in a few lines. While I was still deliberating whether I should send them to Krishnochura, I heard he was no longer amongst us. If only I could have sent it to Krishnochura when he was alive!

Professor Ashraf was a source of inexhaustible humor, and it made him a personable figure. I can still recall one day in an exam hall when there was a commotion in the end. He along with several female teachers was invigilating the exam, and the female ones were groping for means to squash the uproar, saying, “Those who have script B must submit it to us, the female teachers; on the other hand, those with script A should submit it to him, Ashraf sir”.

He rose to his feet and noticed no change in the commotion. After a minute or two, he started, “A for Ashraf. A for Ashraf. Please give script A to me. Remember A for Ashraf”. Who would forget the day?

It was such an obvious example of his ready wit. While students 'come and go talking about Michael Angelo', his was a completely different classroom, a veritable cornucopia of it if you will. Allusion is another kind of ready wit he seemed to have been eternally endowed with. We could remember he had taught us Yeats' “Second Coming” in the previous semester. In the next, he taught us a different course, but while going out of the class, he forgot his mobile set. When he returned a few minutes later, Dr. Fakrul Alam had already started his class. Now he had to interrupt us, so he quipped, “Sorry for my 'second coming” as he was going out, gathering his phone set.

On yet another occasion when he was busy checking our scripts, he said, “You are getting so many 'marks'. You are all being 'marxist' (marks+ist)”—an unforgettable pun that we would all invariably miss henceforward.

Often he would make fun of himself as well. He had a slightly dark complexion and a slightly bald head, and these two often became more than his body features. Many of his jokes about himself elude my mind now, but ask any of his students, and you will still see a whiff of laughter, the vestiges of their class participation and learning under the effectual, inimitable tutelage of this doyen.

The last of his qualities that riveted our attention, motivated our minds and, above all, stupefied us was his honesty, dedication and passion. When he entered the classroom, a reassuring ambience would prevail. I do not know if he subscribed to E. M. Forster's theory of teaching, “spoon feeding in the long run teaches us nothing but the shape of the spoon”, but all the years I studied under him I noticed him avoiding 'spoon feeding'. Before coming to the class, he always seemed to have well prepared himself so that every single query students might pose would receive a mind-kindling answer. Ever dedicated and honest with his profession, he would, every day before starting a new topic, recapitulate whatever we had done before. Therefore, the literary theory that he lately offered us still seems vivid in our memory.

Although a teacher cannot teach experience proper, he always taught us from his experience. While teaching us Keats' “Ode to a Nightingale” in the second year, he balked at the lines depicting the requiem:

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain— To thy high requiem become a sod.

As was for Keats, it was a climactic moment for Khondakar Ashraf Hossain in the poem. Addressing the nightingale, Keats says if the bird still sings when he will die, he might not have a human ear but he would still be listening to it. He aspires to be a tuft of grass or soil thrown on the grave while the requiem is being played. For Professor Ashraf, it was the last wish too, and he wished when he would die, there should be some music all around.

It was just the beginning, the opening gambit of his obsession with death towards the sunset of his life. When his wife died towards the end of our undergraduate program, I remember he would almost always say that once his “sathi” (friend, comrade) and soul-mate, his wife, had left him, there was nothing left for him to press ahead with. While returning from the funeral prayers held at the premises of the Dhaka University Central Mosque, some of my friends, Halim, Maidul and Abir, commented that Hossain's health must have deteriorated after the demise of his wife, and maybe it was what hastened his death.

I do not know if their surmise would all be true, but I was not at all startled at his death. He had always wished it; he wished the faster it came, the better. I am not sure if there was music all around when he died either. But I am sure he must have heard something, something that left his face smiling even in his death.

Professor Dr. Khondakar Ashraf Hossain, even if you are no more amongst us, let me be a 'sod' at your grave when you listen to the celestial music, the eternal ambrosia in the blissful seclusion of your village, ever sequestered from the hustle and bustle of mundane life.

The writer is a master's student of

English Literature at Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments