You Need To Know What Happened To Private Banks Last Week

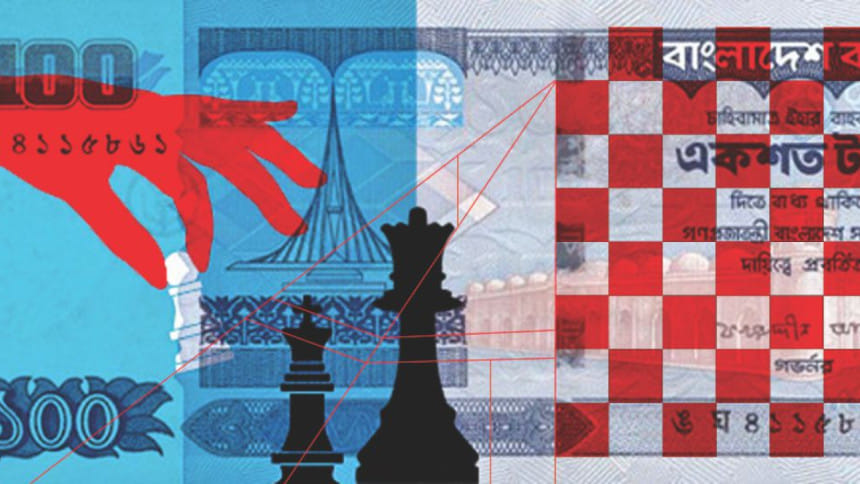

People have been talking about it from the beginning of the year, and whispering about it for longer—private banks are going through a liquidity crisis. There is not enough money in hand to make the rounds, and the extent of the problem came to light last week when the government had to intervene to help them deal with the crunch.

The government offered to let government offices deposit 50 percent of their funds in private banks, raising the deposit limit from 25 percent. The government is also lowering the mandatory cash reserve (known as Cash Reserve Ratio or CRR) that all private banks have to keep with the Bangladesh Bank as a fail-safe measure. Previously they had to maintain 6.5 percent; it has now been cut down to 5.5 percent.

All this was done by the government because the interest rate for loans is in double digits, impeding business, the Chairman of Bangladesh Association of Banks, Nazrul Islam Mazumdar, told The Daily Star last week.

How did the private banking sector get to this point is really the question.

The private banks blamed the media, stating that media coverage of bank scams led to a frenzy of depositors withdrawing their money. The Bangladesh Association of Banks (BAB) rushed to propose that a “Bank Reporting Act” be created. In a meeting with the Finance Minister, AMA Muhith, private banks sought the government's help in “controlling” media. BAB Chairman Nazrul told The Daily Star that even reporting “accurate information” can lead to trouble in the banking sector, and that the media should recognise that—essentially telling journalists that they should not be reporting on bank scams. It was clear that he was alluding to the back-to-back investigations done by the media into the privately owned Farmers Bank Limited scandal, where it was found that the bank defaulted on BDT 852 crore worth of clients' deposits.

Transparency International Bangladesh Executive Director Iftekharuzzaman slammed the proposal. He told newspapers that the public has a right to information about corruption in the banking sector.

For sure the public—and perhaps more importantly depositors—have a right to know about their banks. Way before Farmers Bank went bankrupt, and way before angry depositors (including 14 government agencies at least) complained to the Bangladesh Bank this year, the media had forecast the ruin of the private institution. As early as 2016, reports surfaced about the high volume of bad loans given by the bank to individuals already identified as loan defaulters. An investigation by Bangladesh Bank during that year revealed how the bank was disbursing loans without adequate collateral and mortgage. They concluded that Farmers Bank was essentially being used as a sack of gold anyone could reach into whenever they wanted.

The public also definitely have the right to know about the fact that among the funds that the bank lost was money for the Climate Change Trust Fund worth BDT 508 crores. Nor would it in any way be right to deprive the public of the information that taxpayer money is now being used to bail out the crippled bank. Towards the end of March, the government took the decision of injecting capital worth BDT 715 crore into the bank from the state-owned Sonali, Janata, Agrani and Rupali banks, and Investment Corporation of Bangladesh. To add more context to this fact—the Farmers Bank failed to pay back BDT 700 crore worth of short-term loans which they had taken from Sonali Bank, Agrani Bank, Janata Bank and NRB Global Bank towards the end of November last year. Of the amount, nearly half was being covered by the state-run Sonali Bank. Last Tuesday, the Anti-Corruption Commission placed an embargo on the managing directors of this private bank, forbidding them from leaving the country.

Under such circumstances, is it prudent to suggest that the public be kept in the dark about bank scams in private banks? Hardly.

The reason behind the liquidity crunch ultimately lies in the culture of being reckless with depositors' money—a vice that both state-owned banks and private banks indulge in, except the former are unconditionally insured by the government. The year 2017 was the first time that private bank profits took a dip in five years, shouldering the brunt of bad loans. Syed Mahbubur Rahman Chairman of the Association of Bankers, Bangladesh, confirmed to The Daily Star at the end of last month that private banks are not seeing profits solely because of the volume of non-performing loans.

There is an abundance of literature on the state of bad loans in the country. To add rigour to the claims, however, we can cite a 2017 Bangladesh Bank study published last year that explored exactly what the situation of bad loans was like. The survey titled “Field Survey Report of Study on Credit Risk arising in the Banks from Loans Sanctioned against Inadequate Collateral” studied 41 banks and 574 defaulters. They covered Dhaka, Chattogram, Khulna and Bogura. The survey found that 88 percent of total outstanding loans by National Bank of Pakistan were non-performing loans, followed by ICB Islamic Bank Limited at 76.4 percent, Bangladesh Commerce Bank Limited at 31.6 percent, State Bank of India at 14.6 percent and Habib Bank at 14.6 percent. By comparison, a strong bank like Citibank NA only had 1.93 percent of non-performing loans.

The survey also explored how this came to be, asking the tough questions about nepotism, and for sure the researchers were not disappointed. They found the banks sanctioning loans based solely on personal relationships, not taking into account whether the debtor had enough collateral to offer. To make the situation worse, their documentation was weak leading to a gap in knowledge about the people they were lending to. The survey also reported that politically influential people sought nepotism from top-level management when it came to loans. Sometimes the nepotism took a darker turn and turned into undue pressure, leading bank managers to overlook factors like the borrower's credit risk. In fact the research found that since the banks do not follow a common standard for examining the market value collateral, it allows borrowers to use it as a loophole and influence decisions. Most of the non-performing loans also belonged to industrial borrowers, they found, hinting at the existence of a nexus between politicians, big businesses and banks.

The finding that nepotism and political clout play a significant role in the disbursement of bad loans is even more alarming when put into context with a recent amendment made to the law governing bank management. The Bank Company (Amendment) Bill 2018 was passed in the parliament in January, and will allow a commercial bank's board of directors to have up to four members of the same family. Furthermore, a bank director can now hold a place in the board for nine years at a stretch, up from what was previously six years. This amendment divided the parliament, inciting the criticism that this will weaken the collective ownership needed to keep banks strong, and line the pockets of individual families instead.

The Bangladesh Bank researchers also observed that not all the banks had strong enough departments needed to assess a person's credit, or evaluate the worthiness of collateral. As a result, persons identified as habitual defaulters fall out of their radar. An example remedy would involve banks sharing a registry of all their collateral, while Bangladesh Bank can maintain a central data hub on the different values of different collateral.

In light of the fact that experts are concerned about the scenario of bad loans in private banks, how effective would the recent government moves be, in tackling the liquidity crisis?

Experts suggest that the government's measure to reduce the Cash Reserve Ratio, so as to allow private banks to have access to more liquid capital is not the way to go. Zahid Hussain, Chief Economist of World Bank's Dhaka office wrote in The Daily Star last Monday, “Most analysts agree that the underlying cause is deficit in corporate governance in these banks, particularly in the loan risk management and collection of non-performing loans. Banks who have done badly in these areas are the ones having the most difficulty in complying with the CRR. The CRR reduction will help them avoid the penalties for non-compliance, but it does little to incentivise improvements in corporate governance.”

On the other hand, Dr. Ahsan H Mansur, Executive Director of the Policy Research Institute told The Financial Express that the government's decision to allow their departments to deposit 50 percent of their funds into private banks, should only be limited to strong banks. The idea is definitely worth noting seeing that Farmers Bank made off with so much money from the Climate Change Trust Fund.

The Bangladesh Bank study also proposed reforms that could be taken into consideration to improve governance. For example, they recommended that loan defaulters who are also the members of different chambers of commerce not be allowed to participate in elections. They also suggested that banks can coordinate among themselves to ensure that a current loan defaulter is not able to get another loan until the dues are settled.

Yet who would the government be to recommend these reforms, when our state-owned banks remain debt-riddled for years. The government is to once again bail out Sonali Bank, Janata Bank, Rupali Bank, Bangladesh Krishi Bank, Rajshahi Krishi Unnayan Bank, and Grameen Bank with an amount of BDT 2000 crores (BDT 20 billion); an amount which is apparently only 10 percent of what they need. Compared to this, the bailout package of the Farmers Bank scam is a drop in the ocean. This is hardly the first time that these banks are being rescued. When the state is allowing its own house to run amok, how will it fix its neighbours'?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments