Origins of the global anti-drug movement

How many of us actually know that the origins of the United Nations' (UN) ban on harmful drugs go back to the imperial drug trade in Bengal from 1757 to 1925? A revisit to colonial history in South Asia would give us the right answer.

P. Godfrey, in a letter to Fort William in March 1757, indicated that the British East India Co. (BEIC) established its monopoly trade in opium along the West Coast by October 1754, and had 'prohibited' all other parties 'from trading therein'. A similar intent animated the BEIC for capturing the political throne of the Kingdom of Bengal within a span of three years. George Watt, in 1891, documented that the sudden attack by Siraj-ud Daula over the Kashimbazar military base broke the supply line of Patna opium to the British, and that led to the Battle of Plassey in the following year. A similar content was maintained by James F. Finley in 1894, that suggests Siraj-ud Daula's attack drove the English merchant out of the drug market, with the 'cultivation of opium being greatly restricted'.

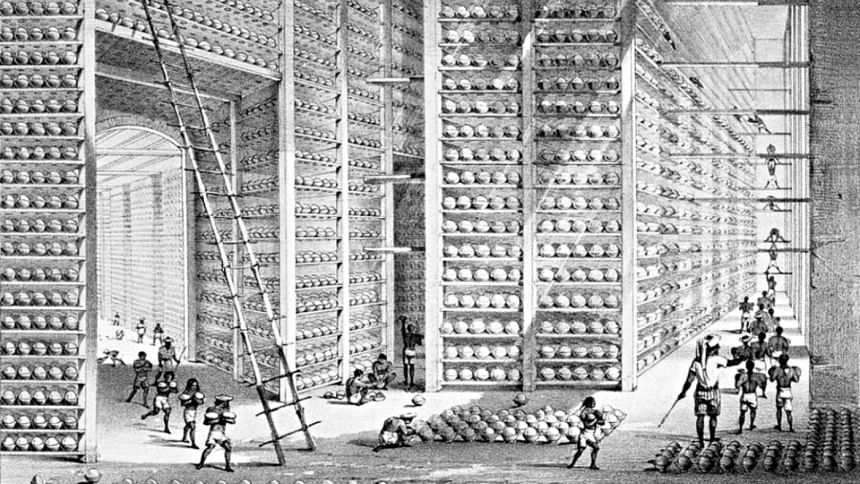

Upon capturing state power, the BIEC founded the Bengal Government Opium Monopoly in 1773. China became the major market where the British smugglers forcefully drifted illicit opium into different port cities. It resulted in 30 percent addict population in China, of whom 10 percent were chronic patients, coupled with the losing of silver currency to the British. In a futile attempt, the Chinese Emperor had banned opium trafficking in 1800, and were then locked into Opium Wars against the naval coalition led by the UK at the turn of the 1840s and then in mid 1850s. China lost 20,000 marine soldiers and had to recompense costs of War every time.

Alongside, forceful cultivation of opium poppies in an area of 120,000 square miles created tremendous sufferings and hardship for the impoverished poppy ryots in Bengal, Bihar and UP. Under the two opium agencies in Patna and Benares, a five tier Opium Administration was installed, run by separate British collectors. Classical economist Adam Smith recorded the British intimidation, "A rich field of rice or other grain has been ploughed up; in order to make room for a plantation of poppies; when the chief foresaw that extraordinary profit was likely to be made by opium."

In order to break the supply chain, the poppy farmers in Bengal and northern India, fought courageously in the Revolt of 1857. Looking down upon it, however, colonialist writers often referred to the event as a 'Sepoy Mutiny'. The Imperial Government adopted the Opium Act of 1856 and then the Opium Act of 1878 to further consolidate its control over its production and exportation.

By the late 19th century, however, public opinion started to rally across South Asia, China, UK and North America, against the colonial drug trade, thereby compelling the British government to set up a Royal Commission on Opium in 1893. In this state-managed voluminous report, the imperial government tried to evade the problem by arguing that "opium taken in moderation" was "good for health"! As a retort to the report, the US government formed the Philippines Opium Commission in 1906 in its newly occupied colony, where addiction was a grave problem. To counteract the Philippines report, the colonial government formed the Ceylon Opium Commission in 1908, but admitted the medical evidence of opium addiction.

The latest reports expedited the Shanghai Opium Commission in 1909, whereby 13 European countries, including the US and China, formed a collective move. The Hague Convention of 1912-14 codified and expanded the agreement reached in Shanghai about the abuse of opium, cocaine and morphine, but the colonial government in India boycotted it to evade international pressure. In order to help the global initiatives, the Indian National Congress in 1924 formed the Assam Opium Commission that gave a detailed account of opium addiction in that area. These factual evidence and records helped the League of Nations to place a ban on international drug trafficking through the Geneva Convention of 1925.

Sensing its farewell bells, in the absence of drug revenue, the colonial government adopted the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1930 and then the Bengal Opium Smoking Act of 1932. With these legislations, the colonial government, for the first time, admitted that opium lead to addiction.

Furthermore, the League of Nations in 1936 adopted the Convention for the Suppression of Illicit Traffic in Dangerous Drugs, making drug trafficking for the first time as a criminal offense. It called upon governments to punish people involved in this activity regardless of their nationality and of the country where they committed this crime. During the post-World War era, the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961 consolidated the various drug treaties and protocols the UN had inherited from the League of Nations. Then, the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 imposed stringent controls on a number of synthetic substances not previously covered. The most recent cornerstone of the UN's anti-drug framework, the Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of 1988, recommended "optimal governance structure" for dealing with the drugs problem.

In accordance with the latest framework, Bangladesh formed the Department of Narcotics Control (DNC) in 1990. Since its inception, however, structural weaknesses and problems related to capacity building have been common phenomena with the DNC. The department is not well equipped to tackle the challenges posed by the vested quarters in the underground world throughout the region. Contradictory and pro-revenue policies pursued by the supply side countries are also posing additional dimensions to the threat posture. Especially, a strategic shift of the "War on Drugs" to "War on Terror" by the US has been another global concern in the new millennium, while the current narcotics trade amounts half a trillion dollar.

In view of the facts, adequate national budget should be allocated to the DNC to address the internal governance structure and reduce the demand and supply side issues by a skilled and motivated workforce. Alongside the anti-militancy strategies, bilateral treaties should be drawn on harmful drugs with next-door supply side countries, while their faithful implementation will remain crucial for the "War on Drugs" in our region. Every date in the calendar, not just June 26, should be monitored by all stakeholders as the UN Day Against Drug Trafficking and Drug Abuse.

The writer authored Drugs in South Asia: From the opium trade to the present day (Palgrave Macmillan, UK & St. Martin's Press, USA: 2000).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments