Nobanno: The Old Bangla New Year

Long before people knew how many months made a year; or how many days made a week, they would welcome a New Year when they were happy. Nature determined when and how the New Year would be welcomed.

In ancient Iran (Persia) people welcomed the New Year with the first blooms of spring. The happy Persians named their New Year 'Nowruz' (the new day). Nowruz became synonymous with spring. Before Roman colonisation, ancient Europe too celebrated New Year in spring. In our part of the world, nature determined the New Year in a different way. It was related to agriculture, marking change in weather.

The three great rivers -- Ganges (Padma), Brahmaputra (Jamuna) and Meghna -- form one of the largest deltas in what is today's Bangladesh. These rivers and their tributaries have made this land one of the most fertile in the world. For thousands of years agriculture has shaped the livelihood and the economy of our people. Before the Green Revolution, the agricultural calendar had two crop seasons: 'Aush' and 'Aman'. Of these, Aman was the harvest farmers would wait and pray for like a 'tirther kaak'. The Aman crops would be ready for harvest in Kartik (mid October). Kartik would also signal a change in the air. Hemanta (late autumn) had arrived.

With pleasant weather and surplus food grains, rural Bengal was happy and ready to welcome the New Year the next month in Agrahayan (mid November). Ancient Bengal named the festival 'Nobanno' (New Food). Until Emperor Akbar's transformation to make Baishakh the first month, for centuries, Pahela Agrahayan or Nobanno was the New Year of rural Bengal and its people.

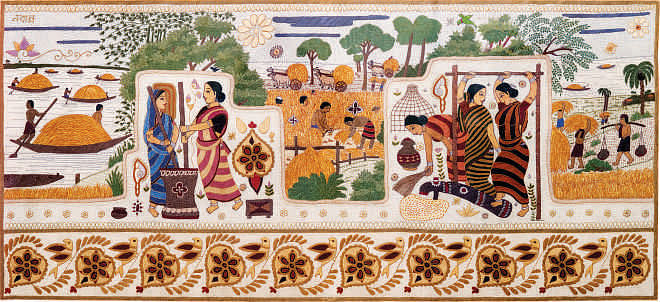

A farmer's fate would be determined in Kartik. A good harvest meant the family was safe for one more year. There would be food with which to celebrate Nobanno. The harvest would transform into pitha, khoi, muri, mowa, payesh and what not. Hemanta would paint the green fields and the banks of the rivers white with kash flowers. Singers would sing. Dancers would dance. Kites would decorate the blue skies. Rural Bengal would overspill in festivities with fun fairs and squeaking noise of the nagordola. Women would immortalise the spirit of Nobanno with tapestries (nakshi katha) like the ancient Egyptians did with their hieroglyphs that spoke of their times and their civilisation.

Nobanno wasn't always good. Weather could be unpredictable. The harvest was fickle like dew on a lotus leaf. And with it, the fate of farmers could change from day to night. A bad harvest would mean a shortage of food for the next year. Rural Bengal didn't have too many safety nets as it now has. Farmers would find themselves locked into an almost inescapable bond with the local money lender.

Times have changed. Today Bangladesh enjoys food surplus. The Green Revolution with its mass irrigation means the winter harvest ('Boro') is now larger than the Aman harvest. One of the best road connectivity in South Asia means the rural landscape of Bangladesh is slowly becoming more urbanised and more commercialised. Rural people now have more opportunities outside agriculture. Becoming a middle income nation is no longer a dream. It's just a matter of time.

Tradition is something people don't give up that easily. With the annual Pahela Baishakh carnival and the Jatiya Nabannatshob Udyapan Parshad, Charukala (Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka) has kept alive traditions that define the fabric of the culture of Bangladesh. Go to Bakultala at Charukala. Relive the tradition of Nobanno -- the Old Bangla New Year.

Asrar Chowdhury teaches economic theory and game theory in the classroom. Outside he listens to music and BBC Radio; follows Test Cricket; and plays the flute. He can be reached at: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments