Unpacking the Islamist Agenda

Since the Shahbagh movement began in early February, demanding the maximum punishments for the war criminals and the banning of Jamaat-i-Islami (JI), there has been a flurry of activities among the Islamists. Various groups and alliances have emerged. The organisers of the Shahbagh movement, popularly called the 'Gonojagoron Moncho', have repeatedly clarified that they were not calling for the outlawing of Islamist parties, nor for any constitutional changes that would disenfranchise the Islamists. The government has indicated that it has no plan to proscribe Islamist parties including the JI. These statements failed to pacify the Islamists, who looked for another issue and came up with alleged anti-Islamic activities of the organisers of the uprising. The uprising was initiated by a small group of young bloggers and online activists. Although it has drawn hundreds of thousands of people, spread all over the country and received significant support from the diaspora Bangladeshi community, online activists remained at the core of the movement. The Islamists claim that these bloggers have demeaned Islam and dishonoured the Prophet Muhammad in their blogs and online comments. Lack of knowledge of Islam and ill-conceived remarks may well have featured in online comments of some bloggers; they were not the leaders of the movement nor was religion itself an issue of the movement.

The brutal killing of a blogger on 15 February, followed by massive propaganda that he had previously made blasphemous statements in his blogs, brought the issue to the forefront. To the surprise of many, the central issue quickly became the organisers and their faith -- instead of the demands they had been pressing for. The organisers and by extension those who support them were branded atheists and apostates. Caught off-guard, the organisers played into the hands of the Islamists as they sought to defend themselves against these charges. The violence perpetrated by JI activists throughout the country for five days after the sentencing of Delwar Hossain Sayeedi on 28 August, the death of at least 80 people, alleged excesses of the law enforcing agencies, the lack of protection of religious minorities, the government's tardiness in meeting the demands of the Gonojagoron Moncho and other pertinent issues have been pushed to the backburner. The Islamists were joined by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) in their verbal assault on the movement organisers. The battle cry of the Islamists has become 'save Islam, stand up to the atheist, and apostate.' In an apparent change of the political landscape, Islamist groups of different shades have once again become prominent players, and the political discourse has centred on the religious credentials of targeted individuals.

To comprehend the trajectory of this emerging situation it is necessary to examine the various trends within Islamist politics in Bangladesh in general, closely scrutinise the key Islamist parties and identify the newly minted alliances.

Islamist parties in Bangladesh: An overview

Islamist political parties can be categorised in two ways: either using participation in electoral politics as the defining criterion, or based on their principal traits.

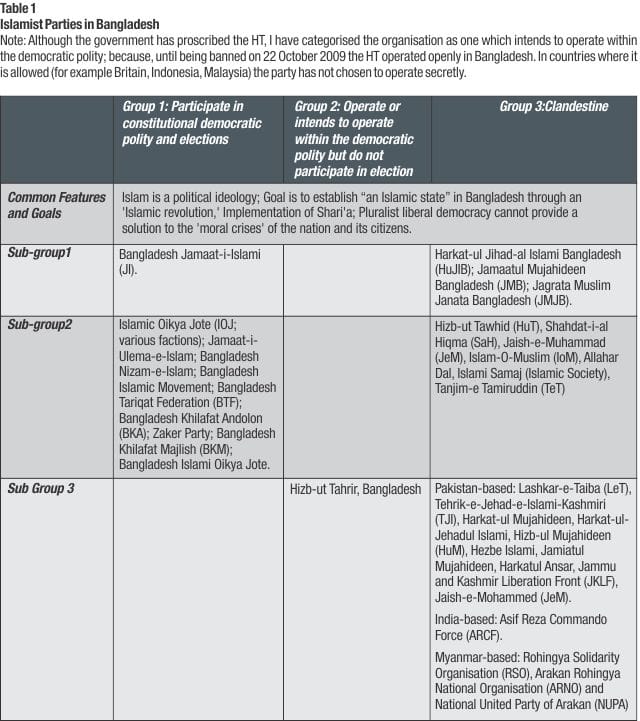

Electoral participation as a criterion: According to the electoral participation criterion these parties can be grouped into three broad strands: those who participate in the existing political system and elections; those who operate within the democratic political system despite reservations but do not participate in elections; and those who refuse to take part in constitutional politics and remain clandestine. These three groups share the common goal of establishing an Islamic state in Bangladesh through an 'Islamic revolution,' even though they have differences on many issues, including the ideal disposition of an Islamic state. Additionally, they agree that pluralist liberal democracy cannot provide a solution to the 'moral crisis' of the nation and its citizens. Political parties belonging to the first and second strands do not openly subscribe to the ideology that violence is the only means to achieve their goals, but they are not totally averse to using violence if needed. The third group, on the contrary, espouses violence as the only means to establish an Islamic state and has remained outside the traditional political arena. These groups are small and have very little popular support, yet they pose serious challenges to democracy, governance and rule of law. They tend to take advantage of political uncertainty to surface (Table 1).

Within the first strand of Islamist politics there are at least three sub-groups. The JI is the largest representative of the first strand and represents one subgroup. (Much has been written on JI in recent days. I will focus on other Islamist parties in this essay). Various other Islamist parties constitute the second and third subgroups within the strand. They participate in mainstream constitutional politics and in elections, in some cases grudgingly. The differences between parties representing these three sub-groups are personal rather than ideological, although the leaders frequently couch their differences in ideological terms. The defining feature of the second subgroup within this strand is opposition to the JI. Although some of these parties are not averse to the idea of working with the JI they prefer to maintain some distance. The Islamic Oikya Jote (IOJ, the United Islamic Front) is a case in point. Both the JI and IOJ were partners in the four-party coalition government (2001- 06) led by the BNP. In the past two decades, other Islamist parties have tried to curve out a distinct space in the political arena. Each party has tried to separate from the JI, and emerge as the leader of Islamist politics The HTB is the country chapter of the HT, a leading political movement in Central Asia currently headquartered in London. It launched its Bangladesh chapter on November 17, 2001. It envisions a Shari'ah-based Khilafah state. HT is the only Islamist organisation to speak of Khilafat, and to acknowledge its international connection. According to press reports and close observation HT has gained most momentum through its activities at the country's universities. What makes the HT distinctly different from other Islamist political organisations, including the clandestine ones, is that its political agenda is not confined to Bangladesh, but is a global one. The group is placed within the third sub-group because of its international connection.

The third strand comprises the clandestine groups. These organisations can be divided into three subgroups. Prominent among the clandestine militant organisations are the Harkat-ul Jihad-al Islam Bangladesh (HuJIB), the Jamaat-ul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), and the Jagrata Muslim Janata Bangladesh (JMJB). These three organisations, however, can be traced to a single network. Some of the leaders of these organisations reportedly are or have been members of the JI. Although the JI has denied any such link, the profiles of key JMB leaders arrested in 2006 indicated that at some point of their political careers several of them were involved in JI politics The second subgroup of the militant organisations includes Hizb-ut Tawhid, Shahdat-i-Hiqma, Jaish-e-Muhammad, Islam O Muslim, Allah'r Dal, Islami Samaj, Tanjim-e-Tamiruddin. There are indications that members of these organisations are ideologically closer to the smaller Islamist parties (some of which were part of the IOJ alliance and now operate as separate entities) than the JI. Profiles of the militants arrested since the beginning of 2006 indicate that former participants of the Afghan war and disaffected youth are at the helm of these organisations. The third subgroup of clandestine militant organisations includes both those which originate outside the country and those which are operating within the country. According to intelligence reports in 2010 at least 15 external militant organisations had a presence in Bangladesh. These groups primarily use the country as a training base, recruiting centre and transit point.

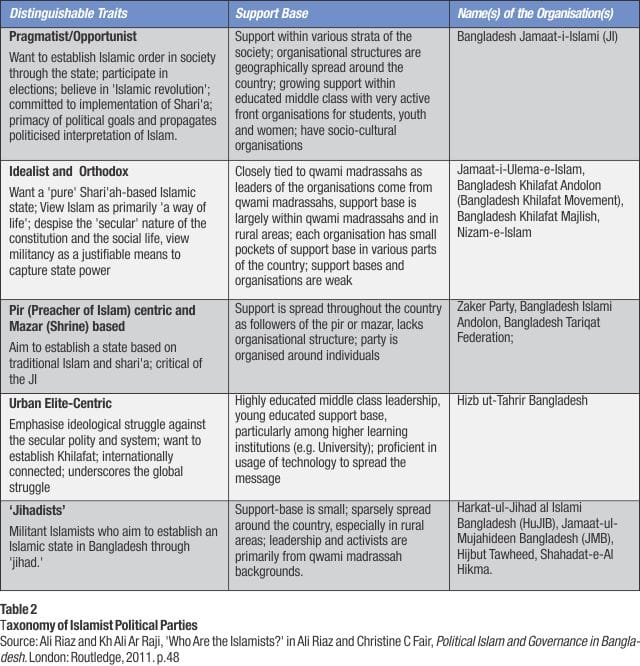

Distinguishing traits as a criterion: Based on these defining traits the Islamist political parties can be divided into five categories: pragmatists, idealists, pir (Preachers of Islam) and mazar (Shrines) -centric, urban elite-centric, and 'jihadists'. Of the five categories of Islamist parties, those which fall within the first four operate within mainstream politics while those in the fifth category are clandestine and some have been proscribed since 2005. Table 2 also looks at the support bases of the political parties included in each category.

Contemporaneous developments

Seven distinct camps of Islamist parties and organisations have emerged in recent days. The central issues for these camps are: the future of religion-based politics, banning of the JI, and the opposition to, what some are describing as, 'anti-Islam and atheist activities' of bloggers. Among these camps one that has received a great deal of attention in the press, both local and international, is the Hefazati- Islam (HI).

Hefazat-i Islam: Hefazat-i Islam (HI) came into existence in early 2011 as a platform to oppose the national women's development policy of the government. The genesis of the group, however, can be traced back to 2008. Soon after the announcement of the draft Women Development Policy by the caretaker government, Islamists and various Islamic social organisations protested despite the fact that political activities were banned at that time. Although this move was initiated by ulema and clerics, political forces, especially the IOJ soon took the leading role. The JI leadership extended their support, but had very little presence on the street. JI's absence was not a policy decision but a tactical move; it was unwilling to appear confrontational vis-a-vis the caretaker regime. The situation altered in 2011 when the present government implemented the Women Development Policy. The mainstream Islamist political parties, such as the JI and the IOJ, with the support of the BNP came forward to voice their opposition and called a general strike. But ulema associated with qwami madrassahs saw this as an opportunity to insert them into the leadership and launched this organisation. These activists were largely connected to the qwami madrasshas in the greater Chittagong area, but received support from the ulema associated with qwami madrassahs in other parts of the country. The Ameer of the HI is Director General of the Hathazari Madrassah Mufti Shah Ahmed Shafi, who is also the Chairman of the Bangladesh Qwami Madrassah Board. The organisation held a grand conference of various Islamist parties, organisations, and ulema of qwami madrassahs on 9 March in Hathazari madrassah. This conference was attended by at least four parties which are also part of the BNP-led 18 party combine. These organisations are IOJ (Aminee group), Khelafat Majlish, Nezam-i-Islami party and Jamiat-e-Ulema-Islam.

The 12-party front: The front named 'Islamic and like minded 12 parties', came into being in early 2011. Parties comprised in the alliance were: Khelafat Majlish, Islamic Andolon Bangladesh, Ulema -- Mashaekh Parishd, Bangladesh Khlefat Andolon, Sammilito Ulema -- Mashaekh Parishad, National Democratic Party (NDP), Islami Oikya Andolon, Bangladesh Muslim League, Bangladesh NAP, Nap-Bhasani, Jatiyo Gonotantraik Party (JAGPA), Islamic Party, Nezam-i-Islami Party. The alliance has gone through several reincarnations since its emergence. The alliance organised protests and demonstrations against both the women's development policy and the education policy, but soon lost its steam. Three parties remained the powerbase of the alliance until the beginning of 2013. They were the Khelafat Majlish, the Islamic Andolon Bangladesh and the Ulema-Mashaekh Parishd. However, this grouping, led by the Khelafat Andolon leader Maulana Ahmedullah Ashraf and Maulana Muhiuddin Khan of Sammilito Ulema-Mashaekh Parishd (an IOJ leader), has seen some internal squabbling and reorganisation. For example, by December 2012, the conglomerate faced an internal power struggle. The internal struggle was put on display in December 2012. Eight of the 12 parties withdrew their support from the general strike of 20 December called by the 'Islamic and like minded 12 parties.' The strike was called after the left parties enforced a general strike on 18 December demanding the ban on JI. By 27 February 2013, four parties were pushed out of the alliance and it was renamed the 8 Party Alliance. The four parties which were expelled from the alliance were Islamic Andolon Bangladesh, Islamic Oikya Andolon, Muslim League and the Islamic Party. The leaders of the alliance insisted that these parties were expelled to avoid any controversy regarding the Jamaat-i-Islami as these four parties have close relationship with the JI. But interestingly the leadership remained with the Khelafat Andolon which is known to be very close to the JI.

Council for Protection of Faith and the Country: This alliance, 'Iman O Desh Rakhha Porishod,' was launched on 27 February 2013. The organisers claimed that 'Nine religion based parties' and the ulema of qwami madrassahs have founded this alliance in the face of on-going 'anti-Islamic activities' and to demand harsh punishments for those involved in demeaning God and the Prophet Muhammad. The leadership of the alliance comprises Maulana Nur Hossain Quashemi, the Vice president of Qwami Madrassah Board, as the Convener, and Mufti Shah Ahmed Shafi as the advisor. The parties which joined the alliance are: Bangladesh Khlefat Andolon, Islamic Andolon Bangladesh, Islamic Oikya Jote, Jamiat-e-Ulema-i-Islam, Khelafat Majlish (Ishaq), Khelafat Majlsih (Habibur Rahman), Nezam-i-Islami Bangladesh; Bangladesh Faraizi Andolon, Khelafat-i-Islami. In their first press conference on 27 February 2013 they claimed to have no relations with JI. The alliance did not support the general strike called by the JI on 28 February; and insisted that the alliance has no connection with the ongoing war crime trials.

Bangladesh Islamic Movement: The Bangladesh Islamic Andolon (Bangladesh Islamic Movement) was previously named Islamic Constitution Movement. The organisation changed its name in 2008 to fulfil the registration requirements of the Election Commission. Led by Mufti Syed Rezaul Karim, the pir of Chormonai, the party deserves to be noted separately for several reasons. Among the smaller Islamist parties, it has the most widely spread organisation. In the 2008 election, it filed 166 candidates throughout the country and secured 733,966 votes -- 1.05% share of the total cast votes. Except the JI no Islamist party has ever received popular vote of more than 1% in any previous elections. The second factor that makes the organisation notable is its effort to curve out a space on its own as opposed to joining an alliance. That being said, it is not averse to building a larger alliance to press for its goals. In recent months, it has maintained close relationship with all the Islamist alliances. For example, party representatives have attended the 9 March 2013 grand conference at the Hathazari madrassah called by Shah Ahmed Shafi, but has not joined the HI led programs. Instead, it has called separate demonstration programs against the 'anti-Islamic forces'. In late March, Syed Rezaul Karim commented that both the BNP-led 18-party alliance and the AL-led Grand Alliance are deceiving the Ulema. He called upon the ulema to unite under the banner of Islamic ideals.

Bangladesh Islami Oikya Jote: Although the name Bangladesh Islami Oikya Jote suggests an alliance, it is an organisation led by Misbahur Rahman Chowdhury. The organisation is a splinter group of the original IOJ. It is a member of the ruling Grand Alliance. The organisation demands the ban of the JI and alleges that the JI and its student wing Shibir have committed un-Islamic acts in the name of Islam. It also demands that government take stern actions against those who have dishonoured Prophet Muhammad. It maintained a very low profile in the years between 2009 and 2012, but launched a series of programmes since the demand of banning of the JI grew louder. Interesting to note that, despite being a member of the ruling Grand Alliance, the party didn't join the Progressive Islamic Alliance which comprises three other Islamist members of the alliance.

Progressive Islamic Alliance: The alliance, named the Progotoshil Islami Jote, came to existence on 12 December 2012 with 4 parties as members. These four organisations are Bangladesh Tariqat Federation, Bangladesh Islamic Front, Bangladesh Sammilito Islamic Jote, and Gonofront. These organisations are known to be adherents of Sufi tradition, and insist that they believe in the spirit of the 1971 liberation war. The alliance is headed by Syed Nazibul Bashar Maizbhandari, the leader of the Tariqat Federation (TF). The TF was established in late-2005. Maizbhandari is closely connected to Bangladesh Dargah Mazar Federation (BDMF). Among the members of the alliance all but the Gonofront are members of the AL-led Grand Alliance. The demands of the alliance include the banning of the JI and punishments of the war criminals. Other demands include identifying and punishing those who have made demeaning remarks about Islam and Prophet Muhammad.

Bangladesh Ulema-Mashaekh Towhidi Janata Sanghati Parishad: The Solidarity Council of Islamic Scholars and Devoted People emerged in March 2013, in response to the various Islamist groups' increased activities challenging the Shabagh movement. The council is led by Farid Uddin Masud, the former Director General of the Islamic Foundation and currently the Khatib of Sholakia mosque. (Sholkia holds the world's largest Eid congregation after Mekka.) He is the co-chair of the Bangladesh Qwami Madrassah Education Commission appointed by the government in April 2012. Early in his political career Farid Uddin Mashud was a leader of the Jamiat-e Ulema-i-Islam and once led one faction of the party. In the past decade he was engaged in creating network of madrassahs named Iqra. These madrassahs are part of an organisation called the Islahul Muslimeen. Masud is known to be anti-JI and close to the ruling AL. These landed him in jail after the series of bomb explosions by the banned Islamist militant group Jamaat-ul Mujahideen Bnagladesh (JMB) on 17 August 2005. During his court appearance on 24 August 2005, Masud insisted that then Minister JI leader Matiur Rahman Nizami is connected to the bombing.

What do we know now?

It is well to bear in mind that the political landscape since the Shahbagh movement emerged is far more complex than it appears. Equally true is that some conflicting trends are at play. However, a few observations can be made from the preceding discussion on the contours of Islamist parties in Bangladesh and their current roles. First, despite strategic and tactical differences, Islamists of various shades share the common objective of establishing an Islamist state. Second, there is a long-standing contestation between the JI and other smaller Islamist parties. In the past decades, the JI has shrewdly played its electoral cards and took advantages of major political parties, the AL and the BNP; by doing so it has succeeded in disproportionately influencing the Bangladeshi politics. JI's success has also created an expectation among other Islamist parties that they too can influence the political trajectory -- either as a single party or as an alliance. Thirdly, with the ongoing trials of the JI leaders and the growing demand for the banning of the JI, the smaller Islamist parties are at one level sensing an existential threat (thus challenging the Shahbagh uprising, opposing the government's moves to weaken the JI, and being supported by the JI) while at another level viewing this as an opportunity to emerge as the spokesperson of the Islamist (if the JI is forced to vacate the space of the kingmakers. Thus they are flexing their muscles). Fourth, the recent emergence of the Islamist alliances do not indicate that new Islamist forces are on the rise; instead closer examination reveals that various raucous alliances (i.e. Hefazat-i Islam, The 12-party Front, and Council for Protection of Faith and the Country) are only different combinations of the same political parties. Fifth, three new alliances, (and the constitutive parties), share the same support base (qwami madrassahs) and are idealist and orthodox in orientation. Finally, as the three alliances have flexed their muscles, it is evident that the pro-government Islamist parties and alliances have been made active. This indicates a strategy of facing Islamists with Islamists. One immediate consequence has been obvious -- the political discourse is now dominated by the Islamists' agenda. There is no denying, this has long-term implications.

Ali Riaz is University Professor, a companion honour to Distinguished Professor, at Illinois State University, USA. He teaches political science and is author of several books on Islamist politics in Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments