For blacks, Jackson’s struggles mirrored their own

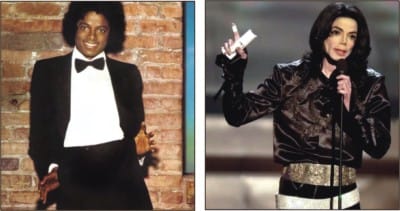

The transformation of Michael Jackson

The strange story of Michael Jackson is especially strange for his loyal black fans, who watched with pride as he became the biggest entertainer of the last quarter-century.

Yet loving Michael Jackson -- his artistic genius and the many trails he blazed -- has often meant looking the other way when it came to his appearance. Over the years, his face became increasingly unrecognisable, amusing and perplexing his fans while becoming the living embodiment of the identity crises many black Americans have struggled with for almost 400 years.

Like “The Cosby Show,'' which debuted around the reign of Jackson's “Thriller,'' he made race seem revolutionarily inconsequential without rendering it irrelevant, in much the same way Barack Obama would do decades later.

Jackson moonwalked through doors opened by Jackie Robinson, Nat King Cole, Harry Belafonte, Martin Luther King Jr., Sidney Poitier, and Muhammad Ali, and he is usually mentioned alongside Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, and the Beatles. He was a crossover genius.

Like everybody else, black Americans sprint to the dance floor when a DJ plays “Don't Stop Til You Get Enough'' at a wedding, or turn a supermarket into “Soul Train.'' But at the same time, they identify with him because they understood his sadness.

The question he forced is this: How beautiful is black? To turn one's back on Michael Jackson was in some powerful, if barely conscious way, to turn back on one's own struggles with blackness.

At several beauty salons and barbershops across United States, where Jackson's death last Thursday remain on everyone's mind, the sentiment seems to be that Jackson lived at the poles of black pride and insecurity.

In 1993, Jackson told Oprah Winfrey -- and, by extension, the entire planet -- that he struggled with a skin condition called vitiligo that drained the pigment out of this skin. Regardless of whether this was actually the case, his face itself told the story of a torn soul. By the time of his death, he had become the perverse personification of the “double-consciousness'' that W.E.B. DuBois described more than a century ago in “The Souls of Black Folk.''

“It is a peculiar sensation,'' DuBois wrote, “this sense of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity...The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, this longing...to merge his double self into a better and truer self.''

Through his ongoing plastic surgeries and increasingly pale skin, Jackson took this longing to a kind of tragic extreme. The African features of his youth that he had been conditioned to loathe -- through his troubled upbringing, through the limiting funhouse lens of popular culture -- steadily disappeared. His wide bulb of a nose became a precariously slender triangle. His ice-cream-scoop Afro and, later, his juicy Jheri curl dried into cascade of straight, ravenous hair. And his brown skin became a chalky mask with a model's cheekbones, a starlet's doe eyes, and a matinee idol's cleft chin. Jackson had grafted America's white beauty myth (for both genders) onto his face.

Look hard enough at Jackson, however, and you realise that it was aging, not blackness, that he hated. Each new birthday brought him further from the childhood he felt he never had but never stopped trying to capture and restage. Race was bound up in that attempt to reconstruct a new ageless self. He was a black Dorian Gray, with his diminishing but still robust record sales as his portrait.

For all his alterations, Jackson never forsook his roots. From his earliest days with the Jackson 5, his voice was electric with gospel and soul. His music was alive with the layered rhythms of afro-beat (“Wanna Be Startin' Somethin''') the sex of classic soul (“Human Nature''), and, and in later years, the thump of new jack swing, and urgency of hip-hop. Part of the reason black Americans never turned their backs on Jackson was that Jackson never turned his back on them.

During the early 1990s, Jackson's cosmetic changes and sense of persecution actually mirrored deeper changes in his songwriting. The lighter his skin got and the more on trial he felt, the angrier and more political his music became.

The world premiere of the first video from his 1991 album “Dangerous,'' for a song called “Black or White,'' was a national event.

The song was a ditty about an interracial relationship in the crosshairs of intolerance. The video brought out all the song's fiery undertones (“I'm not gonna spend my life being a colour,'' goes the rap), with Jackson shouting the heavy metal-lite bridge in front of images of exploding flames.

The video ends twice, first with the utopian image of faces of various colours morphing into each other. Then, in a kind of epilogue, the music drops away, and we watch Jackson attack a car with choreography and a crowbar. It was Fred Astaire by way of “Do The Right Thing,'' and it was surreal.

At the Image Awards in 1993, he looked nervous but also unusually serene. In a sense he had come home, and the audience of black politicians, fellow stars, and artists seemed to enthusiastically identify with him.

They could see well past the bleached skin and unnatural Caucasian features. They could see his blues.

Compiled by Cultural Correspondent

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments