Stories from Nepal

Writing in a May 2008 issue of the 'London Review of Books' about turbulent Nepalese politics, Manjushree Thapa began with a memorable line, "In Kathmandu, the conventional wisdom has it that you show up early on voting day: the lines at the booth may be longer, but the chances are that no one else will yet have voted in your name. And trouble, if it comes, comes in the afternoon."

That same striking combination of sharp insight and clear prose has marked her out as the leading English writer from Nepal. It was very much in evidence in her 2006 nonfiction account of Nepalese Maoists, Forget Kathmandu: An Elegy for Democracy, one of the more superior pieces of reportage to come out in English on Nepal before the Maoists laid down their arms and participated in elections. It was a clear-headed tour through the tortuous maze of Nepalese power politics--including that Shakespearean palace massacre that effectively was the death knoll of royal rule--that ended with an unforgettable account of a hike through the remote, then-Maoist-controlled mountainous western region of Nepal. The trek itself seemed to symbolize that, unlike the general run of women writers in South Asia writing in English whose social concerns and involvement come to rest at the borders of gentility, Thapa had no inhibitions about logically extending it to wherever it took her.

Manjushree Thapa was born in Kathmandu in 1968 and studied at St. Mary's school there. Later she was at the National Cathedral School in Washington D.C. and at the acclaimed Rhode Island School of Design, where she majored in photography. She then got an MFA in creative writing from the University of Washington. Her first book, Mustan Bhot in Fragments, was a travelogue, after which came the novel The Tutor of History. But it was Forget Kathmandu, coming out of seemingly nowhere, that made her a Nepalese voice to watch out for.

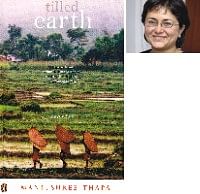

In this collection of short stories, titled Tilled Earth (Penguin Books India; New Delhi: 2007), one again sees that interweaving of social engagement, realistic appraisal, and what without much demur on anybody's part can be termed as crystalline prose. The stories here range from the short short story (half a page) to the long short story, and written with an abiding knowledge of modern-day Nepal, especially of Kathmandu, its gristle and bone, its alleys and goats. Allied to it is an implicit questioning of modernization and development, and of the West, and the Westerners it brings in its long train, of failed democracies and tottering state structures. Present at times is a satirical bite, oblique, true, but nevertheless there--in, for example, the short story extract reproduced here ('Soar')--in deliberate counterpoint to an exoticized Nepal. Overall, two fine stories dominate the fare, 'The European Fling' and 'The Buddha in the Earth-Touching Posture.' The former is a hard-headed look at the conflict between tradition and modernity through Sharada, a Nepali woman, and Matt, an American man. The two "of them had slept together one drunken night, years back at Boston University," and now both of them rendezvous in Europe decades later, to test the limits of Matt's proposition that "love was a bourgeois construct designed to entrap women's labour." In the latter story a bureaucrat leaves his wife, and travels to Lumbini, the birthplace of Buddha, and comes face to face with himself.

As NGOs and NGO workers, urban decay, rural poverty, government civil service members, dusty ceiling fans, agendas, reports, verandas, small-country angst proliferate in her stories, they become stories of South Asia. Not just a Bangladeshi reader, but all South Asian readers, would have no problems connecting with her stories and understanding the lives, and life, she recounts.

This identification is underscored in the very texture of her language. In Thapa's stories people wear 'mufflers' and 'jean-pants', to just give a couple of examples. And in the same manner, woven in the texture of the language are subtle differences too: our 'rickshaw' becomes a 'rickshaa', and the same mode of transportation, ubiquitous and familiar, acquires that Nepalese difference through the twist in spelling and pronunciation.

Tilled Earth is both a delightful and thoughtful read.

Khademul Islam is literary editor, The Daily Star.

Soar

Putting the water to boil, Nadia remembered that she was supposed to call someone about something, but she couldn't remember who or about what. Was it a gender specialists for next week's women's rights seminar? About trafficking, rape, child prostitution, domestic abuse, the lack of basic rights for Nepali women? This hangover was killing her. With shaking hands she picked up the day's Kathmandu Post and scanned the headlines before turning, slowly, to the back pages. There was nothing much in the international news. When she heard the kettle hiss she put down the paper and with some effort made a pot of coffee. She took a cup to the living room, along with the paper. Instead of reading it she examined a potted banyan plant she bought the previous week. A few fresh leaves had uncurled overnight: delicate and moist, vulnerable. Under her breath she sang to them: 'Shall I soar above these hills and peaks?' It was a folk song she had learned on a trek a few months after coming to Nepal, when she believed there were simple solutions to simple problems. 'These hills and peaks,' she broke off. She didn't know the rest of the words. She lifted the coffee to her lips but it was too hot to drink. For a while she looked at the corner of the window ledge, where the egg sacs of spiders had appeared a few weeks back. When would the eggs hatch? She looked awhile at their silky bundles. Then she went back to re-reading the Kathmandu Post. The local news was in fine print on the third page. Woman, she read. Woman Considered Witch Forced to Eat Faeces by Villagers. She put the paper aside and gulped down her coffee.

At lunch Nadia flipped through brochures for package holidays to Pataya, Colombo, Goa, Blue waters, white sand. She thought: one gets so wrapped up in the woes of this country one forgets how easy it is to leave. An hour's flight to Delhi, three to Hong Kong and eighteen to the apartment she had given up in Brooklyn eighteen months ago.

When she got home from work that evening she found the maid standing on a window ledge, dusting a hard-to-reach corner. It always surprised her how Nepali women could manage in saris: all those pleats and folds did not seem to trip them up. There was such--resilience--in Nepali women. The maid was lithe despite being middle aged. Nimbly, she stretched across the window ledge and, as Nadia watched on, she reached for the spiders' egg sacs and picked them off with on deft pinch, killing the larvae inside.

That night Nadia got through a bottle of Shiraz scanning United Nations manuals on evacuation provisions in case of emergency.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments