Royalty, aesthetics and the story of mosques

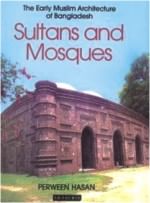

Perween Hasan, Sultans and Mosques: the Early Muslim

Architecture of Bangladesh. London: I. B. Taurus, 2007.

In his remarkable study, The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier (1997), Richard M. Eaton observes how Bengal first achieved cultural autonomy from the Delhi Sultanate in the fourteenth century. This, he points out, was the period when the "first indigenous reference to "Bengal" itself is to be found. Eaton notes that "the emergence of the independent Ilyas Shahi dynasty" at this time "represented the political expression of a long-present cultural autonomy". After the North Indian armies gave up their bid to exercise strict control over the frontier province and a sovereign dynasty emerged decisively, Bengal remained relatively undisturbed for a fairly long period. Not surprisingly, the now confident rulers of Bengal embarked on building mosques and monuments that would attest to their "imperial glory". This was also when Sufi saints began proselytizing in the region vigorously, but in a manner that was rooted in indigenous traditions as well as imported ones. One consequence of the consolidation of the Sultanate and the rise of Islam was an efflorescence of Islamic architecture in eastern Bengal.

But while Eaton comments on the cultural autonomy evident in Sultanate Bengal and notes the size and grandeur of some of the monuments of the period, his interest in cultural-political history prevents him from concentrating on the mosques and mausoleums of Bengal from the perspective of a historian of architecture. He was thus not in a position to add to the observations to be found in A. H. Dani's Muslim Architecture in Bengal (1961) or make use of the brief and scattered comments of others who had studied the buildings of the period. Nor was he able to glance at the detailed descriptions of some of these monuments that appear in specialized monographs and scholarly journals. Since Dani's study is far from exhaustive and since a lot more research on the Sultanate period has been done in recent decades, the time was surely right for a work that could not only take advantage of all the extant scholarship on the subject but also look anew at these monuments, scrutinizing them as never before and laying them out in their full splendour for posterity's benefit.

It is the singular achievement of Perween Hasan's Sultans and Mosques: the Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh that she manages to not only draw on the existing scholarship on early Islamic architecture in Bengal but also extend it significantly by surveying the Sultanate monuments thoroughly and by documenting them with a highly trained eye. In her carefully structured, exhaustively researched and elegantly produced work, Hasan has not merely lived up to her claim to have diligently "collected all the documentation available in an effort to fill at least some of the gaps in our knowledge of these mosques"; she has also endeavored to investigate them anew to present before readers the most complete and visually satisfying book on them. To accomplish her goals, Hasan visited "every monument to make measured drawings" and analyzed their floor plans systematically to discover the true dimensions of "the original structures". In other words, in what was clearly a labour of love, she strove to document their distinctive as well as representative features. In the process she has succeeded in writing the definitive book on the subject and has left all students of the Sultanate period and of the religious and cultural history of medieval Bengal indebted to her scholarship.

Hasan's Sultans and Mosques begins with a chapter on the geography, history and culture of Bengal that is notable for the succinctness with which she provides the contexts of the mosques and monuments she will detail in later chapters. What she stresses in the chapter is "the extent to which Islam was reshaped to suit the Bengali environment", a point that is crucial in understanding the unique architecture that developed in the region. But Hasan makes a concluding point in this chapter which has important implications for all of us confronted now with the version of intolerant, fundamentalist Islam that is being aggressively thrust upon us by vested interests at this time. As she puts it: "The cultural identity and the psychic mould of today's Bengali Muslims is rooted in the liberal attitudes of the Independent Sultans of Bengal who permitted Bengali culture to flourish and combined it with Islamic influences brought in from the central Islamic lands". In other words, Islam has been most dynamic in the region when it melded with indigenous traditions and not when it tried to hold on to some atavistic and wholly imported and impossible notions of purity.

Chapter Two of Sultans and Mosques amplifies Hasan's observation about the way "indigenous forms were used to create a new type of building" perfectly suited "to meet the congregational needs" of a rapidly expanding Muslim community all over Bengal. She notes how the do-chal or chau-chala roofs everywhere visible in Bengali villages as well as temple designs noticeable in buildings of pre-Islamic Bengali culture eventually led to the mosques and monuments of the Sultanate period. She is able to show how the religious buildings of the restored Ilyas Shahi dynasty of the fifteenth century and the Husain Shahi dynasty that straddled the fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries "lacked monumentality" and had "low domes and low facades and curved cornices, thereby fitting "nicely into the local cultural milieu". What is even more interesting for the subsequent architectural history of Bengal is how the Sultanate mosques "in turn influenced sixteenth- to nineteenth-century temple constructions". Here too Hasan's argument gives the lie to those who strive deviously to establish notions of cultural purity and ignore the essential syncretism of Bangladeshi civilization. Once again, Hasan's book scrutinizes history to come up with a conclusion about a vibrant phase of our history that is relevant for us now: "The Muslims adopted a pre-existing form, adapted it to their needs, enriched it, and then shared it with the culture from which it had originally come. The non-Muslim culture readily accepted it".

In identifying what is unique about the mosques of the period, Hasan also notes astutely what the builders of Bengal decided not to borrow or import. She thus points out the absence of minarets, traditionally associated with a mosque, except in the Shaitgumbad mosque of Bagerhat (which, she stresses, is also exceptional in its monumentality). She identifies multiple mihrabs (helpfully glossed in her excellent glossary as "niche indicating the direction of Makka") as another distinctive feature of the mosques of Bengal. She comments too on the way the central mihrab is emphasized in mosque design. Another characteristic feature of the mosques and monuments of Bengal that testify to their rootedness in the artistic traditions of Bengal is their terracotta decorations.

A fascinating aspect of Sultans and Mosques is Hasan's pages on the stylistic evolution of the monuments of Bengal. She comments first on the building styles that existed in the period of Turkish rule and the early Sultanate period, drawing on whatever evidence is still left of the architecture of the period. She next takes into consideration the mosques and a tomb that survive from the middle Sultanate period. This along with the mosques built in the style associated with Khan Jahan and the buildings of the late Sultanate period become her central concern in the rest of the book. She points out the way these styles were displaced by the architectural perspectives introduced first by the Mughals and then the British, observing intriguingly in passing how it has survived in Hindu temple architecture in Bengal and how it was gradually exported to other parts of India.

The long third chapter of Sultans and Mosques consists of a catalogue of Sutanate mosques in Bangladesh. Proceeding chronologically and systematically, Hasan provides detailed information about the location, date, condition, dimensions, constituting material, plan and elevation, decoration (wherever applicable) of fifty-five mosques of the early, middle and late Sultanate periods, encompassing the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries respectively. As she explains in the prefatory comments to her catalogue, she had surveyed "all but nine" of the monuments herself. The descriptive part of the text is well supported by clear drawings of the plan of the monuments and vivid photographs of distinctive aspects of the exterior and /or interior of the buildings. Finally, each entry is followed by a bibliography that lists the extant scholarship on these buildings.

The only thing that Sultans and Mosques lacks is a conclusion. This is a lacuna in the text that will bother any discerning reader. Why, one wonders, was Hasan reluctant to end with some reflections on the larger implications of her work? Why, one keeps thinking, was she unwilling to go beyond cataloguing the early Muslim architecture of Bangladesh? Surely, there are many questions that she could have pursued to a close. Surely, she could have come up with insights that could have opened up further avenues of scholarly investigations for subsequent researchers. Anyone who has read the Foreword written by Oleg Grabar, Aga Khan Professor of Islamic Art Emeritus, Harvard University, and the scholar who "initiated" Hasan "into the study of Islamic architecture' will be reminded of her timidity in this regard by the searching questions he poses so confidently from his readings of the book. More observations situating her work in a wider intellectual and cultural context and some amount of theorizing and speculation would undoubtedly have made this an even more valuable work. One can only hope that this is exactly what Hasan will be doing in her subsequent work for she is too learned a scholar to be constricted to cataloguing and description, important though such work always is!

Dr. Fakrul Alam is a writer and critic and teaches in the Department of English, Dhaka University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments