Chile: September 11, 1973

AP/CTK

Salvador Allende Gossens was elected president of Chile in September 1970. Having earlier made several electoral attempts to win the presidency, Allende, a Marxist, was now poised to enter the La Moneda presidential palace with 36.2 percent of the vote.

Little did his followers realise, at that point in time, that conspiracies and intrigues were already afoot to undermine his government even before it took office. Allende was expected to take over from the outgoing rightwing president, Eduardo Frei, on October 24.

But already the rumblings of discontent, most notably in distant Washington, were beginning to be heard. President Nixon and Henry Kissinger, his national security adviser, had tried in vain to prevent Allende from riding to victory because they felt that the rise of a Marxist leader through elections in Latin America would lead to disaster for capitalist interests. In a remark that sounded facetious before the election, Kissinger had remarked that he saw no reason why a country should "go Marxist" only because "its people are irresponsible."

Once Allende's triumph became a fait accompli, though, Richard Nixon went ballistic. In the Oval Office, he spoke to Richard Helms, the CIA director, and told him specifically that Allende must not be permitted to take office. Helms' notes reveal the paranoia that swept the White House that autumn.

This is what Helms noted down of Nixon's directives: "Not concerned risks involved. No involvement of embassy. $10,000,000 available, more if necessary. Full-time job -- best men we have . . . Make the economy scream. 48 hours for plan of action."

Over the next few days, the CIA, with Nixon and Kissinger behind it, went looking for officers in the Chilean military to undertake the responsibility of keeping Allende from taking the oath of office. It was a difficult job, especially because Chile had, through all the long seasons of coups and illegitimate governments in its neighbourhood, held on to its democracy.

Another difficulty for the Americans, as they tried fomenting a putsch in Santiago, was the presence of General Rene Schneider, the chief of general staff and a man holding full conviction in constitutional government.

It was at that point that the Nixon White House hit upon the plan of having Chilean CIA agents kidnap Schneider and, thereby, convince Chileans that the general had become the "victim" of Allende's supporters. Major unrest would follow, the army would react, and the president-elect would be prevented from taking power.

On October 15, 1970, Kissinger was provided with the background details of an extreme rightwing Chilean army officer. He was General Roberto Viaux, a man with links to the quasi-fascist group Patria y Libertad (Fatherland and Freedom). Viaux's gang, along with another known as the Valenzuela gang, made an attempt to kidnap General Schneider as he left a dinner on October 19.

The attempt failed, as Schneider left the party in a private car rather than in his official vehicle. The gangs made another attempt the next day, October 20. It did not work. On October 22, General Viaux's gang, failing to kidnap Schneider, simply assassinated him.

Allende, undeterred, took the presidential oath of office on October 24, 1970. One would have thought an exasperated and exhausted White House would call a halt to its plans to undermine him. However, that was not the way things would turn out. Over the next three years, the CIA, with its agents scattered throughout Chile and Latin America, worked assiduously to bring down the Allende government.

There was Operation Condor, a euphemism for promoting destabilisation in the region and undermining its democratic forces and essentially sponsored by the military regimes then in control of much of the South American continent. By early 1973, the conspiracy to free Chile of its democratically elected Marxist administration was reaching a definitive turning point.

Rightwing political parties and other groups, patiently cultivated by the CIA, kept up a noisy refrain of demonstrations and protests against the government. As autumn approached, lorry and truck drivers, paid handsomely by the CIA, went to work putting up barricades all over the country. The goal was, yet, one of instigating the military into overthrowing the government.

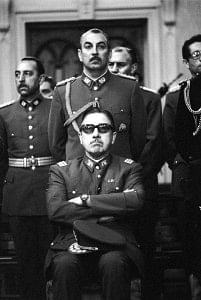

General Carlos Prats, the chief of the army and a firm believer in the continuity of Chile's democratic traditions, was ridiculed by the wives of officers working under him over his "failure" to save the country. Depressed, he resigned on August 22, 1973. The next day, President Allende appointed General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, considered to be loyal to him and to the constitution, as the new commander of the army.

Unknown to Allende, however, Pinochet quickly got in touch with the Americans on the ways and means of neutralising the government. Over the subsequent two weeks, Pinochet sought, and gained, the support of the air force, navy and police for a coup d'etat against Allende.

In the pre-dawn hours of September 11, the soldiers went to work. By 6 am, Chile's major cities, including Valparaiso and Santiago, had gone under the control of the military. Shortly afterward, air force jets began strafing and bombing the La Moneda presidential place. Pinochet dispatched a message to Allende, promising him safe passage out of the country if he surrendered.

The president, as expected, rejected the suggestion with contempt and went on air to tell the nation he was determined to resist the coup. Around 11 am, President Allende, helmeted and holding an AK-47 in his hands, emerged at the doorway of La Moneda briefly before going back in. It was the last the world would see of him.

By early afternoon, the presidency of Salvador Allende was in ruins and a bloody, ruthless military was in control of Chile. The elected president of Chile was dead, presumably murdered by marauding soldiers.

In the days and weeks that followed, 3,192 people were, officially, murdered by Pinochet's goon squads. The soldiers raided the home of the Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda and ransacked it. The ailing Neruda, earlier Allende's ambassador to France, would die twelve days later, on September 23.

Over the months, thousands more would disappear or be murdered. General Carlos Prats, along with his wife, would be murdered in exile. Orlando Letelier, defence minister in the Allende government, would be killed by CIA agents in league with the Pinochet junta in Washington DC in 1976. The father of Michelle Bachelet, today president of Chile, would be tortured and murdered in military custody.

The rest remains a long tale of searing pain for Chile and its people.

Syed Badrul Ahsan is Editor, Current Affairs, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments