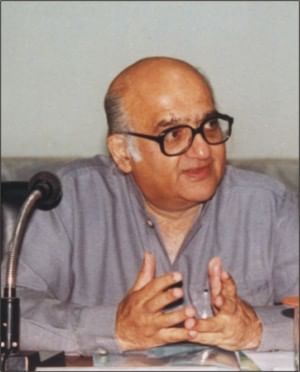

Professor Rehman Sobhan in his own words

It has recently been announced that Prof. Rehman Sobhan is to be honoured with the Swadhinata (Independence) Award 2008 for his contribution to research and training, capping a life-time of service to the nation and the common good. Here we reprint a recent interview with the eminent economist conducted by Badrul Alam Nabil, chief reporter of Saptahik 2000 in which Prof. Sobhan speaks candidly about CPD, the current political situation, and the challenges facing Bangladesh.

Recently, CPD was recognised as one of the top 25 research organisations (civil society think tank) in the world. How has this become possible and how would you define the importance of this achievement?

This was an unanticipated honour for CPD since we were unaware that a list of well-known think tanks was being prepared. The list recognised us as one of the 25 eminent think tanks of Asia as well as at the international level. That we are so recognised perhaps reflects the fact the CPD has established itself as a rather unique organisation which has institutionalised the dialogue process in Bangladesh and across the region.

CPD's tradition of bringing together politicians in the form of ministers, opposition leaders, and parliamentarians with members of civil society drawn from the business, professional and academic community, as well as activists from grassroots organisations representing workers, peasants and the NGO community on a regular basis, is itself rather exceptional. We even periodically involve development partners in the dialogues to get them to debate their policy prescriptions for Bangladesh with constituencies who contest or may be affected by their policy advice. We try to involve all those players who can influence public policy but who rarely interact with each other to address important issues.

In Bangladesh today dialogues have become commonplace and not a day goes by without a dialogue being held on one topic or another. This was not so in 1993 when only a few organisations in Bangladesh, such as BIDS, used to organise seminars and this too was done only on an occasional basis.

Since I founded CPD at the end of 1993 we have organised 216 national level and 34 international, regional, and bilateral dialogues. What is again unique about CPD and even sets us apart from most think tanks around the region, including the most well-known ones in India, is that the holding of dialogues is CPD's primary mission as an organisation. We have established a tradition of preparing reports on and publishing the outcome of these dialogues. In the process we have created an institutional memory of discussions on a variety of policy issues, which is available to both policymakers and academics.

How did CPD begin its journey? What were the background, motivation and objectives?

My motivation in setting up CPD was inspired by my experience as director general of BIDS from 1983-89. I found that we did excellent research there on development issues, but except for a few ministers who were invited as chief guests at seminars organised by BIDS to present our research findings, most of the key political players and business community remained unfamiliar with our work.

When I was a member of the caretaker government under Justice Shahabuddin in 1991 I set up 29 task forces where over 250 of the most able talents in Bangladesh worked together to provide extremely valuable recommendations for policy reforms to serve the newly elected government. But their dedicated efforts were largely ignored by the in-coming government. I therefore become more conscious of the need to establish a permanent forum where we could bring together those who generate ideas for policy change and those who were in a position to use and implement such policies. Such a collective national enterprise to seek answers to Bangladesh's many problems was also intended to help us to recapture our autonomy from the hegemonic policy influence of our development partners.

CPD has mainly been involved with research work, particularly focusing on economic issues, formulating policy recommendations and organising dialogues based on research findings; nevertheless, for the last few years we have seen that CPD has started to take interest in the political situation of the country. In this regard, we can mention the campaign for honest and competent candidates. Why did you feel the importance to take up such initiatives? Why has this movement for honest and competent candidates slowed down after the present CTG came to power, particularly when the present CTG also takes a very strong position against corruption in politics? What are the reasons behind it? Do you have any future plan to rejuvenate the campaign?

CPD was never exclusively committed to work on economic issues, and had from the outset addressed issues with political implications. This included our work on the malfunctioning of our democratic institutions and its impact on poor governance. I myself had written a great deal on these issues for many years. My book, Bangladesh: Problems of Governance, was published in 1993. In 1995 CPD provided the base for the "Group of 5" citizens who attempted to negotiate a political understanding between our two national leaders prior to the 1996 election.

By the time elections were due to take place in 2007, a large section of civil society and even politicians were talking about the need for political reform and the need to ensure a fair election with clean candidates. The 14 party alliance presented a 23 point agenda for such reforms. Today the caretaker government has taken up some of these reform issues though the Election Commission. Much discussion relating to reforms is going on in various dialogues. However, as of now, it is not clear if the emergency rules permit holding of such dialogues at the district level where the Nagorik Committee had, prior to the 2007 election, organised around eleven such dialogues with local citizens prior to the 2007 election. As and when the current situation is clarified by the CTG, it may be possible to resume such dialogues at the local level. Whether CPD will take the initiative in organising such dialogues will depend on whether there is a public demand for us to play such a role.

Often people suggest that the present CTG is the government of the civil society. Our question is how or what type of influence civil society organisations like CPD might have on the present CTG?

It would be flattering to the self-esteem of civil society to see the CTG as their creation, but it would be far from the truth. The present CTG came into existence because one political party chose to subvert the original concept of a non-partisan CTG by imposing a partisan president as the chief advisor, thereby abusing the provisions in the Constitution. The inevitable political confrontation between the major alliances led to the imposition of emergency rule backed by the armed forces. I do not see any role of civil society in this sequence of events.

Due to present government's recent anti-corruption movement, a hostile environment is prevailing in the country's trade and businesses environment, and the negative impact of this on the economy, money supply, inflation, and investment is clearly visible. How can we come out from this?

The ground rules for carrying forward the ongoing anti-corruption drive need to be made clear and consistently applied so that everyone knows where they stand and what to expect. At the same time, the due process of law should be fully applied so that those who are charged will know that they are receiving a fair hearing. This process will be promoted by more transparent conduct by the ACC and continuation of the policy of the head of the ACC of holding more intensive consultations on challenging corruption with every segment of both civil and political society .

Based on current economic trend, what are your observations and predictions regarding the economic situation of the country in the coming days?

There are some dangerous signals being given off by the economy. The price rise is exceptional and is creating insecurity in the minds of most people, but particularly low-income groups as well as the salaried middle class. This anxiety could graduate into anger which could make life difficult for the CTG. The slow-down in investment and industrial activity is also cause for concern and needs to be tackled if employment and economic growth are to be stimulated.

What are the immediate measures that the government should take to bring back or to restore the already lost pace of the economy?

A hard look needs to be taken at how to revive private investment and accelerate public investment through much more effective utilisation of the funds allocated under the Annual Development Plan.

Though both the present chief of the care-taker government and economic adviser are economists, still various types of management inefficiencies are prevailing in the economic and agricultural sector. Why is this happening and what can be done to address these issues?

Placing well-known economists in the CTG does not necessarily qualify them to manage economic institutions. The crisis in the agricultural sector is a governance and not an economic problem. One of the newly appointed advisers, Dr. Shawkat Ali, was agriculture secretary during the time Motia Choudhury was minister of agriculture. These two were ably assisted by Mr. C. M. Anisuzzaman who was agricultural adviser to the prime minister. The three proved to be one of the most successful teams to manage Bangladesh's agriculture. They revived agricultural growth in the economy after several years of stagnation under the previous government.

In 1998 after one of Bangladesh's most severe floods in memory this team ensured efficient delivery of fertiliser and diesel which enabled our farmers to produce our highest ever boro crop. The then finance minister, the late S.A.M.S. Kibria and the then governor, Bangladesh Bank, Dr. Farashuddin, ensured an efficient supply of agricultural credit to finance the farmers for the boro crop.

Dr. Shawkat Ali should be made adviser in charge of agriculture with full authority and support to enable him to replicate his experience of 1998. However, the agriculture team at that time had the advantage of having the backing of an elected government who were aware that they were politically accountable to the country for ensuring an effective post-flood recovery and therefore gave them full political backing.

Since last year, both local and foreign investment has gone down severely. But before that period investment had been increasing significantly. Why couldn't we continue that positive investment trend?

Investment is sensitive to political stability and continuity, since such investments take several years to materialise and generate a positive return. Investors are unsure about the future and also about the rules of the game affecting the condition of their investment. Investor confidence can only be ensured when a predictable political road-map is in place and assurance prevails as to the political order which will emerge and be in place over the life of their investments.

Employers and their federations are claiming that local and foreign conspiracies are behind the continuous unrest in the garment sector. However, employees are saying labour exploitation is the reason behind it. What is your observation on this issue?

Rumours of conspiracies to destabilise the ready-made garment industry (RMG) have been periodically propagated by the owners of garment factories whenever there are agitations launched by disgruntled workers. We have yet to see any concrete evidence of such conspiracies. Whatever hard evidence is available suggests that workers usually have quite specific reasons when they launch an agitation and that they have many genuine grievances which have remained unresolved over the years. More serious attempts need to be made to resolve such grievances.

In the longer run unless workers in the garment sector are made stakeholders in the future of the industry by being offered the opportunity of becoming shareholders in the enterprises where they work, such tension will persist. A social and political order where a small group of owners will live lives of luxury whilst million of poor women workers will walk four hours a day back and forth to their work places, will work in unsafe condition, live in slums, and go on earning $30 a month, year after a year, is not sustainable.

The economy of Bangladesh is basically surviving based on agriculture, ready-made garments, and remittances sent by the NRBs. But all three sectors are facing many challenges due to various reasons. In this situation what are the other sectors that have adequate potential? What support can government provide here?

We have great potential to diversify our manufacturing sector, promote small- and medium-sized industries, diversify our agriculture away from exclusive dependence on food-grains towards higher value crops, and also develop our capacity to participate in the IT revolution. Our governments have done little to strategically plan diversification of the economy and find ways of supporting diversification. Unfortunately the machinery of government is very weak so a future government will need to mobilise the rich professional talents available locally but outside the government to help them in this task.

What are the short-term and long-term challenges as well as prospects for the Bangladesh economy?

The short-term challenge is to stabilise prices whilst protecting the living standards of the low-income groups though various measures which will involve some element of income subsidy and stimulate public as well as private investment. The long-term challenge is to end poverty by giving the resource-poor members of society an opportunity to participate in the development of the economy. We must ensure the resource-poor access to quality education whilst providing them with opportunities to own productive assets such as land and corporate wealth so that 140 million people will become both source and beneficiary of economic growth.

Most of the development activities are now NGO-dependent. To what extent is this situation acceptable for a country like Bangladesh? On a different note there are serious allegations against NGOs that they bring a huge amount of aid in the name of poor people from development partners, but they either invest these in the businesses or consume them by themselves. What do you think?

NGOs have emerged as an important factor on the development scene mostly because of the failure of government to effectively discharge its designated responsibility of delivering credit, education, and healthcare services to those most in need. NGOs have filled this vacuum by drawing on foreign aid from donors who use them as another instrument for privatising the economy. Some of this aid may have been misused by particular NGOs, but much of it has served a valuable purpose in helping the deprived.

NGOs cannot expect to survive by indefinitely depending on aid provided by foreign donors. They will have to become more financially self-sufficient by transforming themselves into income-generating organisations, owned by and accountable to the resource-deprived whom they serve. This may require NGO involvement in some forms of business which generate income which can be utilised to serve the needs of their members who are resource-poor. As long as such commercial enterprises are not misused and their income not diverted for personal gain by the NGO organisers there is nothing intrinsically wrong with some NGOs moving into commercial activities, though this transition will have to be handled with caution and professionalism, as business ventures are potentially risky.

In the long run I visualise some NGOs evolving into corporations owned by and serving the resource-poor, competing with business enterprises. There is no law of economics which says that major business enterprises cannot be owned by resource-poor people.

Though this is a care-taker government, nevertheless it has taken a number of strong initiatives, some of which have already brought positive outcomes. However, in some cases problems have also arisen and the initiatives have been criticised heavily. What can the government do to come out from this situation?

The CTG should not take on too many tasks which are beyond their control and capacity. Their primary task is to organise a free and fair election not later then the end of 2008 and earlier if possible. The CTG and EC should spell out a precise road-map to the elections without further delay to dispel confusion and misgivings. This will involve early consultations with the political parties which will include discussing an early date for the withdrawal of the emergency so as to facilitate resumption of normal political activities.

The consultations should discuss such issues as how to protect the process of reforms for ensuring the independence of the Election Commission, Anti-Corruption Commission, Public Service Commission, and the democratisation of the political parties. Return of the status quo ante would not be acceptable to most citizens and hopefully those in the political process who wish to build strong democratic organisations.

The initiatives for dealing with corruption should continue, but if this is to be sustained after the elections then political parties must be involved in addressing how measures to eliminate corruption can be institutionalised.

Attempts to impose leadership change on the political parties may become counter-productive and could create road-blocks on the way to the elections. If we want to democratise the parties, then the first principle of democracy is to give party members the freedom to elect their own leader.

What is needed is to ensure mechanisms where such an election process for both party leaders and its local leaders are conducted in a free and transparent manner, without resort to intimidation or expenditure of black money to manipulate the choice of the voters. The same principle will need to apply in the conduct of national elections.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments