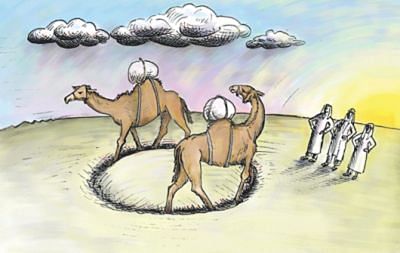

Democratisation effort vs. clientelism and tribalism

Photo: hoover.org

As the Arab Spring heads towards the collapse of decades-old regimes across Middle East and North Africa region, it remains largely uncertain whether this new Arab awakening would lead to a vibrant democratic Middle East. There are a number of socio-political and cultural factors that might facilitate or hinder the democratisation process in the region. This article aims to highlight some of these issues, especially two important factors -- the long-nurtured patron-clientelistic networks developed by the dictators of Middle East and the tribal culture of these societies, that might affect, jeopardise or endanger the democratisation effort and could pose significant challenge to its process.

The first factor that the article aims to highlight is the decades-old authoritarian political culture and entrenched patron-clientelistic networks that could substantially create roadblocks to successful transition towards democracy. Like most undemocratic governments in the developing world, the autocratic regimes in the Arab world have developed their own clientelistic networks to maintain grip on power.

Blessed with abundant petro-dollar, they created strong clientelistic networks to sustain their political authority and assuage political unrest. The network also includes civil-military elites who share power with the regime.

Dictators also strategically distribute public resources, particularly oil and gas rents, and play with politics of infrastructure (distributing resources to core support base), to inhibit or squash the encroachment of uprisings. For example, in response to recent uprising, there are massive housing schemes in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, a 60 percent salary increase overnight in Qatar, food subsidies and outright grants to all Kuwaiti citizens, debt absolution and wage increase in the United Arab Emirates, and unemployment grants and student stipends in Oman.

The dictators have also developed a long-term familial and clientelistic relationship with other political and business elites. In Egypt, for example, Mubarak family and its cronies allegedly amassed billions of dollars when in power. Accordingly, Syrian President Bashar-al-Assad's inner circle that takes key decisions of the government is also comprised of his family members, relatives, long-term friends and loyalists. The same is true in the case of Yemen's Ali Abdullah Saleh, Tunisia's Ben Ali, and other Monarchs and Sheikhdoms in the region. The clientelistic networks that these autocrats developed are much stronger and deep-rooted since they are planted, nourished and served for several decades.

Now, while making an inroad to democracy from this authoritarian clientelistic structure, removing these dictators is only a part of the process. Dismantling the entire patron-clientelistic network is the key in making any real progress towards meaningful democratisation. Without this, the old system can very much spoil the new efforts.

The signs of surviving old system are already there. The reason Hosni Mubarak's party candidate Ahmed Shafik in Egypt secured nearly half of the votes (48%) after Mubarak's humiliating departure is because Mubarak's Bath Party network remains intact. If the vestige of old regimes do not adapt to the new democratic reality, respect the democratic aspiration of the people, this may effectively handicap the democratisation process.

The second factor that remains a source of concern with regard to Post-Arab Spring democratisation process is the ethnic and tribal problems. These two have their own cultural root and political dimension. A glance at today's map of State-society relations in the Arab Middle East reveals that tribes remain a major political actor in Libya, Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Yemen, Kuwait, Qatar, and United Arab Emirates.

In these countries, tribal banners fly next to national flags, and tribal identity continues to play an important role in the shaping of decision-making process of the State, and even in the construction of national identity. Tribal identity in these countries is so strong and dominant that the identity is effectively competing with the two influential identities -- Islamism and nationalism.

Weighing the tribal dynamics in the Middle East politics, Professor Philip Salzman noted in his piece in Middle East Quarterly that, “nothing is more common in the history of tribes in the Middle East and North Africa than battles between tribes, the displacement of one by another and the pushing of losing tribes out of their territories.†Except Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco and Iran -- who have long history in their territory and strong sense of national identities -- almost every other country in the Middle East is tribe dominated who barely feel the very sense of national identity.

New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman termed these states as “tribes with flags.†These tribes often turn violent against each other and the root-cause the regimes in this region become oppressive lies in the heart of this tribal culture. Tribes have their own laws and customs and the regimes usually worked with the tribal leaders to serve demands.

The strength of a particular tribe determines the extent of engagement and relation between a tribe and the government. Hence, tribal strength is the determinant as to defining the status of individuals in a state, which conflicts with the status of individual in a modern democratic state.

While the Western democratic model is built on a basic rule that everyone -- individuals as well as groups -- is constrained not to act with violence but to conduct disagreements and conflicts between them in a peaceful and legitimate manner, the tribal culture in Arab states does not conform to this core norm of democratic ideals.

Besides, the importance of the individual who goes to the poll and votes according to his conscience, not according to the dictates of his family or tribe, often does not work in Arab societies. In most instances, individual in a tribe, so overwhelmingly becomes a part of his tribe that his choices might be overrun by tribal interests.

Elections experiences in tribe-dominated countries, such as Yemen and Jordan, were that tribal leaders play a significant role in shaping the mechanisms and strategies of regimes as well as oppositions.

Friedman pessimistically characterised this electoral impasse in a way that the democratic rotations in power are impossible in these countries since each tribe lives by the motto "rule or die" -- either my tribe or sect in power or we are dead. This inclination seriously challenges the "rules of the game" theory in a democratic state where losing the game (election, in this case) is a regulation and accepting the defeat is a basic norm.

The most consistent criticism of "tribalism" has been that it is incompatible with full participation in a modern state. Literatures suggest that this "primordial attachments" is in direct conflict with civil loyalties and therefore is one of the most serious threats to "new states."

The sense of intractable tribal identity poses significant challenges to the prospect of a new democratic Middle East. If these complex tribal dynamics are not taken into consideration in post-conflict State building efforts, where accommodating conflicting demands and causes would be the key while framing Constitution and other national instruments, the entire process might be jeopardised and ended up in a less promising way.

The writer is an analyst on strategic affairs; attached as a Research Associate with the Institute of Governance Studies, BRAC University. He can be reached at : [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments