African language movement

SOUTH Africa and Bangladesh are two countries in two continents, having hardly anything in common other than the history of language movement and struggle for independence against the minority ruling class.

We all are aware of the glorious history of February 21, which Unesco declared as International Mother Language Day in 1999. However, we do not know much about the costs, toll and achievements of the language struggle of black Africans that took place in 1976.

The day was February 21, 1952 in Bangladesh, and June 16, 1976 in South Africa. In Dhaka, the agitating university students took to the streets and broke section 144, demanding Bangla as the state language, which resulted in open firing and the loss of many lives.

In Soweto, high school black students protested against compulsory education in Afrikaans language, and many children lost their lives when police fired without any provocation. South Africa declared June 16 as "National Youth Day" to recognise the contribution of the youths in the independence movement.

Language had been a medium of oppression all through the history of the world and of civilisation. Linguistic imperialism proved to be much more durable than political imperialism. Therefore, the ruling colonialists always wanted to impose their language and culture so that they could continue to enjoy the local resources as long as possible.

Afrikaans is an Indo-European language, derived from Dutch and classified as Low Franconian Germanic, mainly spoken by ruling whites in South Africa and Namibia. The Afrikaans Medium Decree of 1974 intended to forcibly reverse the decline of Afrikaans among black Africans of South Africa.

In 1976, the government introduced the compulsory use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction from Grade VII -- then Standard V. It had been decided that for the sake of uniformity English and Afrikaans would be used as the media of instruction in schools on a 50-50 basis. Mathematics and social studies were to be taught in Afrikaans, while general science and practical subjects such as housecraft and woodwork would be taught in English.

African parents, journalists, school principals and teachers opposed the imposition of Afrikaans in African schools. They were unhappy -- some applied for an exemption from teaching Afrikaans.

Tensions over Afrikaans were simmering by the mid-year exams of 1976. Students were getting restless. One student wrote to The World newspaper: "Our parents are prepared to suffer under the white man's rule. They have been living for years under these laws and they have become immune to them. But we strongly refuse to swallow an education that is designed to make us slaves in the country of our birth."

The government thought that black school children were becoming too assertive and "forcing them to learn in Afrikaans would be a useful form of discipline." Besides, the government argued, it paid for their education, so it could determine the language of instruction. This was not strictly true. White children had free schooling, but black parents had to pay about half a month's salary a year for each child, in addition to buying textbooks and stationery and contributing to the cost of building schools.

At a meeting called by students under the ambit of Black Consciousness Movement on June 13, 1976, 19-year-old Tsietsi Mashinini, an extremely powerful speaker, suggested that the following Wednesday -- June 16 -- students gather in a mass demonstration against Afrikaans. They decided not to tell their parents, for fear of them upsetting the plan.

It was cold and overcast as pupils gathered at schools across Soweto on June 16. At an agreed time, they set off for Orlando West Secondary School in Vilakazi Street, with thousands streaming in from all directions. They planned to march from the school to the Orlando Stadium. Witnesses later said that there were between 15,000 and 20,000 students in school uniform.

A police squad was sent in to form a line in front of the marchers. They ordered the crowd to disperse. When they refused, police released dogs and threw teargas.

Students responded by throwing stones and bottles at the police. Journalists later reported seeing a policeman draw his revolver and shoot without warning into the crowd. Other policemen also started shooting, which cost the lives of 23 children and injured more than 200.

Twelve-year-old Hector Pieterson fell to the ground, fatally wounded. Mbuyisa Makhubo, a fellow student, who ran with him towards the Phefeni Clinic, with Pieterson's crying sister Antoinette running alongside, picked him up.

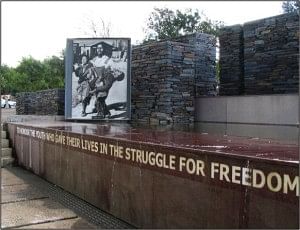

The World photographer Sam Nzima was there to record Pieterson's last moment under a shower of bullets. The photo went around the world and Pieterson came to symbolise the uprising, giving the world an in-your-face view of the brutality of apartheid.

The rioting soon spread from Soweto to other towns on the Witwatersrand, Pretoria, to Durban and Cape Town, and developed into the largest outbreak of violence South Africa had experienced in 1976. Coloured and Indian students joined their black comrades. By the end of the year, about 575 people had died across the country, and 3907 were injured.

The Soweto Uprising was a turning point in the liberation struggle and the fight against apartheid in South Africa. Prior to this, the liberation struggle was being fought outside of South Africa. The Africna National Congress came to the forefront after the Soweto uprising, and the led to the independence of South Africa and overthrow of apartheild in 1994.

The major victory for the students was that they were almost immediately allowed to choose their own medium of instruction. More schools and a teacher training college were built in Soweto. Teachers were given in-service training, and encouraged to upgrade their qualifications by being given study grants.

The most significant change, however, was that urban blacks were given permanent status as city dwellers. The law banning blacks from owning businesses in the townships was abolished. Doctors, lawyers and other professionals were now also allowed to practice in the townships.

30 years after the Soweto uprising, South African President Thabo Mbeki inaugurated the Hector Pietersen Memorial and Museum on June 16, 2006. The city renamed four streets after the leaders of the movement on the same day.

The Museum follows the chronology of the build-up to June 16, 1976, starting with the way tension was building among Soweto's school children, with one school after another going on strike. At the entrance, the famous photo taken by Sam Nzima was placed with a caption: "To honour the youths who gave their lives in the struggle for freedom and democracy."

South Africa had the memorial after having independence, while, in Bangladesh, the historic Shahid Minar remains as a source of inspiration for citizens, in spite of facing demolition several times. However, Bangladesh does not have a state patronised museum to commemorate the history of the language movement even 56 years after the movement.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments