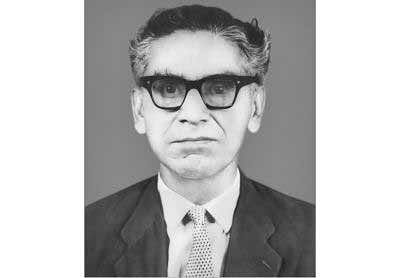

The genius of Abu Mohamed Habibullah

Professor Abu Mohamed Habibullah (1911-1484) was a great historian and humanist scholar of South Asia. Professor Habibullah believed that despite the political divisions of 1947 and 1971, the people of the Indian subcontinent now known as South Asia shared a common and indivisible cultural heritage. This common heritage was the product of over a thousand years of historical development and was the outcome of a long process of blending of indigenous and external elements. These elements had in course of time become inseparable from each other and had contributed to the making of the great and composite cultural tradition of the South Asian region.

In our time, Professor Habibullah truly represented this cultural tradition. I had the good fortune to come in contact with him when I was a student in the postgraduate department of history at Calcutta University sometime in 1943-45. He was then a lecturer in the department of Islamic History and Culture. Although I was not his direct student I used to regard him with great admiration and respect for his profound learning and wide interest and also his scientific temper and humanist outlook. Dr. Habibullah had many similarities with my great teacher Professor Susobhan Sarker. Both possessed a remarkable personality and nourished modern, rationalist and secular ideas. In those days young men of impressionable age like me who were drawn to romantic revolutionary idealism were greatly inspired and enlightened by coming in contact with these two great teachers.

I came to know Dr. Habibullah more closely after he had moved to Dhaka in 1950 and joined Dhaka University as the head of the newly established department of Islamic History and Culture.

Although Dr. Habibullah had migrated to Pakistan he very much disliked the communal politics and reactionary policies pursued by the Pakistan government. The atmosphere was suffocating for him. He sought relief by plunging himself into creative intellectual activities. First, he formulated the syllabus of the newly-established Islamic History and Culture department in accordance with modern requirements. The Islamic History syllabus, he believed, should include not only political history but also social and economic history as well as history of art, architecture and painting. Islamic History had to be taught as an integral part of world history. Islamic culture had to be viewed as part of human culture. Dr. Habibullah believed that Islamic history had to be studied and taught from a universalist point of view so that it could inculcate among students a universal or world outlook and enable them to regard themselves as world citizens. Dr. Habibullah had abhorrence for any kind of tribalism, parochialism or communalism and narrow nationalism or chauvinism.

Professor Habibullah was one of the principal founders of the Asiatic Society of Pakistan, later Asiatic Society of Pakistan, subsequently Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. The Society was established on the model of the Asiatic Society of Calcutta (established in 1784) with the objective of promoting a scientific study of 'Man and Nature of Asia'. Under the leadership of Professor Habibullah and his distinguished fellow scholars like Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah, Dr. Ahmad Hasan Dani and others, the Society became a meeting place of scholars representing different disciplines of the arts and sciences.

During the Pakistan era (1947-1971) the conception of history was linked with a so-called 'ideology' of Pakistan. This ideology was based on the assumption that the Muslims of India formed a single indivisible nation, possessed a distinct cultural identity and hence should have a separate homeland or state of their own where their hopes and aspirations could be fulfilled and they could live in peace and security. This view was held by many Pakistani historians and they received official patronage in propagating it. In 1948, the Pakistan Historical Society was formed with Fazlur Rahman, the Pakistan education minister, as president. Rahman was a Bengali Muslim but in his zeal for the Pakistan 'ideology' he exhorted historians to furnish a justification for the creation of Pakistan by highlighting and emphasizing only those historical factors which tended to show the differences between Hinduism and Islam and conflict between Hindus and Muslims. Evidence of amity and understanding that also existed between the two communities or the syncretic trends manifested in the teachings of Muslim Sufi saints and scholars or promoted by enlightened rulers and princes were deliberately overlooked or misconstrued.

Thus, according to the Pakistani view of history, the greatest Muslim ruler of India was Aurangzeb (1658-1707), who sought to Islamise the Mughal empire, and not Akbar (1558-1605), whose aim was to promote understanding and harmony between his Hindu and Muslim subjects through a policy of tolerance (sulh-i-kul) and patronize a syncretistic religion (din-i-ilahi). But the narrow communal policy of the Pakistan government seemed to have overreached its limits and produced an unprecedented reaction, particularly among Bengali scholars and the Bengali-speaking population of Pakistan. The Pakistan government's attempt to make Urdu the only state language and also the pernicious plan to Islamise the Bengali language by writing it in Arabic script caused widespread resentment among the Bengalis, who comprised the majority of Pakistan's population.

Not all historians, however, toed this line laid down by the Pakistani rulers. Quite a few historians, particularly those of the then

East Pakistan, were reluctant to accept the Pakistani official concept of history which was based on hatred for India and anything non-Islamic. To many Bengali scholars this kind of attitude appeared to be unhistorical, tribal, anti-intellectual and crude. But lest their feelings be regarded as treasonable, they chose the safer path of passive resistance. Meanwhile, the Bengali Muslims were in an introspective mood. For a variety of reasons, mainly political and economic, they had in the past shown unbounded zeal for the creation of Pakistan. But soon after the new state was created they were becoming concerned about their position in the Pakistani political framework, especially when they found that those who held power in Pakistan were mostly Urdu speaking non-Bengalis. They were seeking to use their power to exploit the eastern region of Pakistan for their sole benefit. It was obvious that the ruling coterie of Pakistan were trying to use Islam and Urdu language for promoting their own selfish ends. Systematic onslaughts on the Bengali language and the attempt to distort and destroy the distinct cultural identity of the Bengali-speaking people produced widespread resentment amongst Bengali Muslims and deeply affected their historical outlook. They were now beginning to raise some basic questions. What was the cultural heritage of Bengali Muslims? In what ways were they different from the Bengali Hindus? Could Islam or for that matter any religion alone be the basis of a nation or state in the modern world? People began to lose faith in the myth which had created Pakistan.

It was against this background that many Bengali scholars turned to promoting and undertaking historical studies in the Bengali language from an objective and scientific standpoint. At the initiative of Professor Habibullah, the Itihas Parisad (Historical Association) was established in 1966. In order to arouse greater awareness and interest among people regarding their own history and culture, the Parishad, besides publishing a journal and research works in Bengali, used to hold seminars and conferences in different towns outside Dhaka. At about the same time another association called Itihas Samity (Historical Society) was established with a similar objective. Through this process the Bengali historians contributed in no small measure to the awakening of a new Bengali secular national consciousness which eventually led to the movement for the political independence of Bangladesh.

Professor Habibullah was a man of extraordinary mould. But he never remained aloof or isolated from society. He had a strong and, one might say, revolutionary social commitment. He was a strong opponent of blind faith or fanaticism and orthodoxy of any kind, whether it was religious or political. He would not hesitate to raise his voice against autocracy and dictatorship or fascism. He fully supported the democratic aspirations of the people of Bangladesh.

Dr. Habibullah was a great advocate of autonomy and academic freedom of universities. He believed that the university should not be just a place for cultivation and preservation of old traditional knowledge, but should also be a centre for a creation of new knowledge through scientific investigation and research. Habibullah believed that the university should be a nursery of new ideas and ideals and, in the words of Bertrand Russell, 'an institution of civilization.'

Dr. Habibullah's doctoral dissertation, The Foundation of Muslim Rule in India, is undoubtedly a great historical work. It was first published in 1945. In this work Habibullah showed that after the conquest of India the Muslim rulers had not only founded a new empire in India, they had laid the foundation of a new Indo-Muslim civilization which was the product of a happy blending of Hindu and Islamic cultural elements. Habibullah did not believe in the Pakistan ideology of Muslim separatism. He was a suspect in the eyes of Pakistan government.

While in Calcutta, Dr. Habibullah wrote a number of articles in Bengali which were published in Chaturanga, a literary journal edited by Professor Humayun Kabir. These articles were written in the 1940s, when Bengali Muslims were, in the words of Habibullah, 'afflicted by the Pakistani fever'. In these writings the author's clear and rational thinking was fully reflected. After he moved to Dhaka in 1950, Dr. Habibullah wrote a number of articles which were printed in different journals. A collection of all these articles were published in a book form entitled Samaj Sanskriti O Itihas (Society, Culture and History) by the Bangla Academy in 1974. Another outstanding work of Habibullah was the Bengali tranlsation of Al-Beruni's famous treatise on India, Kitab-ul Hind. Written in 1031 AD, this great work had been translated into English and other languages. Professor Habibullah's translation was, however, from the original Arabic text and profusely annotated and was therefore more authentic. This great work was also published by the Bangla Academy in 1974.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments