Good-bye my friend, it's hard to die —

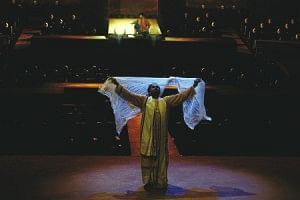

A scene from Pahiye (Hindi translation of Chaka) by Salim al-Deen, directed by the author and produced by the National School of Drama, New Delhi in October 2007

Once again I am reminded of the Mahabharata. Dharma quizzed a thirsty Yudhisthira on the bank of a lake, at the price of his life: "What is the greatest marvel?" All four of his brothers lay dead, having failed to answer Dharma's riddle. The exiled Yudhisthira replied unhesitatingly: "Each day, death strikes and we live as though we were immortal. This is what is the greatest marvel." As I write this, Salim Al-Deen lies buried at the Jahangirnagar University campus. I did not pay my last respects as he lay at Shaheed Minar nor visit his grave. There is something uncanny about a dead person. It is not the pallor but the uncanny stillness. Now Freud admonishes me with a smile: "Everything is unheimlich [uncanny] that ought to have remained secret but has come to light." It is then that Salim Al-Deen's face melts into the lake from where issues once again Dharma's question. I can see my face reflected in the dead. Suddenly, the eyes open. They stare back unblinkingly. I forget my thirst for life. I run away - in exile...

I have not known Salim Al-Deen his entire life - only thirty-four years. This 'knowing' is spread over designing two of his most well-regarded plays, which are now considered landmark productions in Bangladesh theatre – Kittan-khola and Keramat-mangal; directing one of his plays named Chaka thrice: in the USA, India and Bangladesh; and arguing with him incessantly because of what appeared to me to be his follies and flawed lines of reasoning. Now, I can only look back in anger for having missed my chances of unsaying the said and saying the unsaid. Yet, if I did have a second chance, what would I say?

A few months back, he rang me up suddenly one night. The playwright was depressed. His work had not reached out beyond Bangladesh and West Bengal. Life, he said, remained unfulfilled, that he would die soon. I laughed. "You are the greatest playwright in Bangladesh," I said. "I value your work more than Tagore's. Don't hanker after publicity, Salim Bhai. Keep writing. I translated Chaka and will translate other plays soon. I will publish them with a critical introduction on post-colonial theatre in Bangladesh." He spoke for some time, finally said, "Maybe I needed to hear what you have said." That was my last 'encounter' with him. Uncharacteristically, we did not argue or fight. It was as though all our accounts were already settled. I did not realize that it was the time to say adieu. But was it adieu- 'I commend you to God' - and not au revoir - 'Good-bye till we meet again'?

The signifieds endlessly slide under the signifiers, the presence of the word implies the absence of the Real, and we all are obliged to live in language - to endure the impossibility of presence of any object or person of desire. We are always-already living with/in absence - even with those who are 'present'- those not yet 'dead'. Perhaps it is in this impossible dream that theatre exists: of conjuring the 'present' - the 'here and now' - as a lived moment, 'making believe' that presence sips not from cupped palms as we witness the phantasmal rhythm of life from here to eternity. It was here, in this evanescence of theatre that I had hoped to weave my performance of Salim Al-Deen - or perhaps perform my Salim Al-Deen - yet again - and again - for ever - till death do us apart...

I performed Salim Al-Deen's kaleidoscope of a rural fair of Kittan-khola enveloped in winter mist and fog. Tread softly. There, not far from you is Shonai - a marginal farmer in his 30s who will soon be landless because the rising bourgeoisie of Bangladesh can make better use of his fragmented plots. He will kill the man who is out to grab his land, leave behind the haunting memory of his dead wife and seek a new life with a woman of an itinerant snake-charming community. A key event that sets the transformation in motion is a performance of Shamsal Bayati, where he describes the mythical phoenix burning itself on a pyre and the rising of another phoenix from the ashes. As Shonai watches the performance, it connects a high-voltage chord in his unconscious and he swoons.

When he recovers, he asks Shamsal Bayati: "Then which is the truth -- life or death?

: It is an ongoing struggle of metamorphosis, my child. No form is ever-lasting.

: If life is the truth, why have I never attained happiness in living?

: Why do you seek happiness?

: Because there is.

: My child, life is a great joy - sparkling with unbound vivacity. This you will realize at the hour of your death."

What was your realization - Salim Al-Deen - at the hour of your death? As you lay unconscious, propped up with life support system at the ICU of a hospital? Did you not remember the great joy - sparkling with unbound vivacity? But perhaps you had other plans. Yet, I have no tears for you. I refuse to yield you as a corpse and let you descend into your newly dug grave and rot. I refuse because I remember how Anar Bhandari in the play Hat Hadai renounced death and sought life in the pleasures of amorous delight with Angkuri and voyaged yet again across the Seven Seas.

The telephone rings. I pick up the receiver. It is a reporter, wanting a comment on Salim Al-Deen's death. "No comment," I say.

Aren't such soundbites inherently crude as they attempt to sum up a life in one puny little sentence, failing to notice the sliding of the signifieds? One such vulgar comment was made by a theatre pundit in Islamabad, after I had related to him a synopsis of Chaka. "Oh yes, I understand - it's the wheel and life. But it is so clichéd an image!" But when I tried to explain that Chaka is a valuable example to prove the point that a play can be written without dramatic conflict - in contradistinction to the theories of Hegel, Brunetière, Archer and company - the pundit and his attendant flock stared back, utterly flabbergasted!

For such skeptics as these, the only answer can be a performance of Chaka - such as the one we had created in Delhi - which again is not to claim that it too would silence them. Nevertheless, most of them gasped when they saw the 'stage.' It was our macabre joke to sit the spectators on stage and perform the play in the auditorium. And where the spectators would sit, rather where their heads would rest, we put up white masks - all uniformly staring back at the spectators in uncanny silence. In the midst of these death-masks, in a vast space a hundred feet deep and sixty feet wide that was doubled many times over by skillful lighting, the cart-driver of Chaka, along with an old man and a youth, embarked on a journey to deliver a corpse of an anonymous man. They are all poor migrant workers who had set out to seek work at a marshland where summer crops are being harvested. One never learns who the dead man was or how he died, although the corpse is the central character of the play around which the action is woven. As the living trio travel with the dead through rural landscape, each small detail emerges with compelling clarity, melting in phantasmal memories and fantasies of the three, engulfing them with a touch of the uncanny. Even though the presence of the word implies the absence of the Real, and even though we all endure the impossibility of presence of any person of desire, the trio begins to 'touch' the 'dead' in a manner that defies the absence of the Real. The body decomposes, rots, stinks -eyes bulge out, ants attack the flesh - yet the three cannot find its 'home.' The villagers of the address given to them refuse to acknowledge it and redirect him to another village. There, the corpse-bearing cart arrives late at night at a homestead which is more like a blazing vision of a frozen moment of life: the loud-speaker screams a marriage song, the celebrants have dozed off to sleep after a day of hectic labour, and only the bride with her friends - not a Sleeping Beauty - greet them with fearful eyes. Thus driven away from all human destinations, the driver and his two companions bury their dead on a dry riverbed. By that time, the dead had already arisen in of each of them. Thus burying and yet refusing to bury the dead, the three continue for their destination.

Thus as I perform Salim Al-Deen, as I try to piece together a meaning of this man who was called Salim Al-Deen, I ask myself: Do I really value his work more than Tagore? Would not Buddhadeva Bose glare back at me and scoff that "modern Bengali culture"- if such a thing exists, and I believe it does - "is based on Tagore"? Salim Al-Deen would not argue against Bose's opinion. But consider Raktakarabi, which is about a king who has trapped himself behind the iron curtains of a kleptocratic system that extends its network of tentacles even within the private life of the workers and seeks single-mindedly to extract the last iota of wealth with ruthless precision. Tagore sets up a Nandini to rally the king and the common people to destroy the system of subjugation.

My post-colonial location - a discursive product woven by discontinuous fragments of colonial history, now integrated into a totalizing globalizing society through commodity exchange - generates intense skepticism in the comprehension of the world produced in plays such as this. The symbols are so obvious and characters such as Nandini and the King are so blatantly reductive that at no point one reads the world anew with Tagore's lenses. In contradistinction with him, I would insist with Foucault that "the subject (and its substitutes) must be stripped of its creative role and analyzed as a complex and variable function of discourse." A subject (including this 'author') is "not the speaking consciousness, not the author of the formulation, but a position that may be filled in certain condition by various individuals." Subjectivity is formed by discursive practices; it is historically constituted within relations of power. Intrinsic to social life, ubiquitous and multiple, power is that which constitutes and differentiates competing interests and "manifests itself in forms of struggle at the political level. These struggles make subjects what they are."

In performing Salim Al-Deen, we have in theatre what Scholes recognizes as 'fabulation' characterized by allegory, romance, a self-reflexive tendency encouraged by the writer's critical skepticism, and "a sense of pleasure in form" for its own sake. From Kittan-khola to Hat Hadai, one witnesses the dramatist breaking away from norms, abandoning dramatic conflict, dialogue and even a linear cause-to-effect relationship in the development of the action in the plot. Instead, he embraces the narrative as in the indigenous theatre of Bangladesh and infuses his prose with an inbuilt poetic inflexion that situates itself in the interstices of the two categories. He succeeds in what Tagore sought but never could accomplish: breaking completely away from Eurocentric models that has taken hold of urban theatre of Bangladesh and West Bengal. It is here that Salim Al-Deen, in spite of his admiration for Tagore, transcends him. It is here that Salim Al-Deen is unquestionably post-colonial -- to borrow from Gilbert's exploration of a contentious terrain - in that his work exhibits "a strong urge to recuperate local histories and local performance traditions, not only as a means of cultural decolonisation but also as a challenge to the implicit representational biases of Western theatre."

And to this Salim Al-Deen, I bid good-bye - au revoir - till we meet again. Not in life after death, but in the sound of silence when spectators have departed, when I sit alone in the empty auditorium enveloped in its uncanny stillness, when I am confronted once again with the question from the lake, when I realize that the lake melts into your face...

I know you will swagger across the stillness with your characteristic gait, smile and ask, "Where has Peer Gynt been since the last time we met?" (Ibsen) At that instant, I should ask you in return, "Where was I? Myself - complete and whole?" (Ibsen again). But, in the presence of the word that implies the absence of the Real, with the 'self' discursively woven by discontinuous fragments, 'I' will surely miss my cue. Precisely then, I know you will quote Tagore, as though to tease me:

"There is sorrow, there is death, and the pain of separation sears

Still bliss, happiness, and the eternity emerge endlessly within us."

This is the greatest marvel!

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments