An amazing journey from Shahid Lipi to Avro

Photo: STAR

LIKE many chapters of our national history, the amazing journey of digital Bangla -- from English to Bangla computing -- remains largely unknown. Conversant persons should record that history for the new generations. This article however is not an effort to write that history. Rather, I share with you how few geniuses of our time are changing the way we write Bangla on our computers.

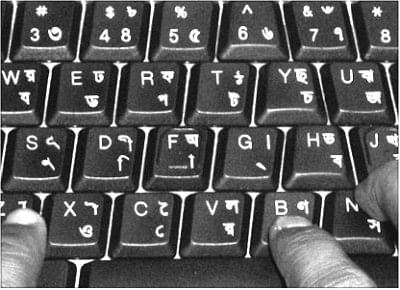

There were three major challenges for Bangla to be written using a computer -- Bangla keyboard, software for the background processing (the main programming), and fonts to display the characters.

Computer keyboards inherited the QWERTY layout (placement of alphabets on keyboard) from typewriters, which were developed in 1874. So instead of inventing a Bangla keyboard altogether, all we needed for Bangla typing was to determine where to place Bangla alphabets on an English keyboard -- be it for typewriter or computer.

In 1965, Munir Chowdhury developed a Bangla layout for a typewriter's QWERTY keyboard to reduce jamming of type-bars and increase the typing speed. This was the first scientific Bangla layout. It was later used in computer keyboards.

But for a computer, having a keyboard "layout" is not enough. We needed software that could process the meaning of the pressed Bangla-labelled key, and fonts-set that could show the Bangla alphabets on the computer screen.

Though there were a number of individual initiatives, "Shahid Lipi" was the forerunner of first-generation Bangla solutions and the first complete Bangla computing interface. Saif Shahid began working on this in 1983 and a complete Macintosh-based version appeared in the market in 1985. He provided a set of Bangla fonts and also offered a Bangla layout, different from the one developed by Munir Chowdhury.

A number of second-generation Bangla solutions hit the market by the end of 1990s. Bijoy, Proshika-shobdo and Proborton led this campaign. While most of them offered unique keyboard layouts, many did not follow the required level of research that Bangla key layout needed.

Since memorising different layouts can hinder the acceptance of new software and make typing complex, some suggested the use of the Munir layout as a basis for further development of Bangla layouts. Later on, Bangladesh Computer Council standardised this layout in National (Jatiya) keyboard layout.

However, continuity and compatibility remained a major problem for many of these second-generation solutions. Mustafa Jabbar addressed this issue by offering long-term entrepreneurial support through Ananda Computers, which hosted a bright team of software developers.

The first version of Bijoy "software" was developed in India (possibly by an Indian programmer). Subsequent versions were developed in Bangladesh by Ananda Computers' team of talented developers including Munirul Abedin Pappana who worked for Bijoy 5.0, popularly known as Bijoy 2000.

From the beginning Mustafa Jabbar provided a different layout for the software, now known as Bijoy layout. Yet, Ananda Computers could easily convince users to accept another new key layout to memorise because of the strong compatibility of its software with other programs. Bijoy software (especially Bijoy 2000) at that time became the most compatible Bangla software to support available publishing software.

However, sharing Bangla texts -- over the internet or between computers -- remained a major predicament. Both parties needed to have similar set of Bangla fonts installed on their computers; otherwise the garbled texts weren't readable. Bangla writing also remained unpopular to the non-professional users who felt discouraged to memorise a complex Bangla layout.

In 1996, the software industry entered the realm of Unicode 2. Unicode -- a universal character-encoding standard that was first developed in 1987 -- allowed virtually any letter from any language of the world to be coded and used under one single standard. Unicode opened up the possibility of having Bangla software that could be used without having to think too much about the fonts.

A number of talented developers in Bangladesh began to experiment with new Bangla software. Many were also influenced by the global Open Source campaign and created Bangla software for platforms such as Linux Mint and Ubuntu, which traditional software could not support.

Through these experiments came a number of Unicode supported software including Ekusheyr Shadhinota and Avro. Later, some traditional software also offered Unicode versions. Though the marvel of these third-generation Bangla software was in their programming, they also wanted to make sure that no one needed to go through another painful process of memorising another keyboard layout.

So, instead of one complex layout to memorise, they included a phonetic keyboard which does not require memorising of the whole layout. For instance, to write pau-phau-bau-bhau-mau one just needs to type P-F-B-V-M. This generated widespread acceptance among individual users.

They also kept the traditional key layouts as an extra option for those who had already memorised them. However, to better suit Unicode and possibly to avoid other patented layouts, these optional layouts did not follow traditional layouts completely.

For instance, the optional layouts of Ekushey and Avro differ from Bijoy and National layouts in some keystrokes and on vowel grapheme. But the unique architectures of the software made it possible to run on versatile platforms (e.g. Linux) where traditional software lagged behind.

Amazingly, most of the third-generation software do not have any business motive and are offered for free. To highlight the significance of being legally free, let me share with you one anecdote.

Before the last national election, the Bangladesh Election Commission conducted the national ID card program, the largest data collection initiative ever carried out in Bangladesh. But the commission faced huge expenditure when it needed to buy licensed Bangla software for each of the thousands of computers/laptops to be used in the project. One of the lowest offers they got from a local Bangla software company accounted Tk.50 million (five crore). Mehdi Hasan Khan, the creator of Avro, let his software be used for free!

I often try to grasp how much love is needed for one's language to be so self-sacrificing. It shouldn't come as a surprise though. After all, in the past we have sacrificed lives to keep our language free.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments