Prof. Sobhan at 75

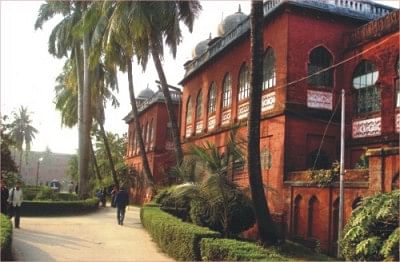

WE have read with great interest the interview of Prof. Rehman Sobhan published in The Daily Star in two instalments. Prof. Rehman Sobhan belonged to the elite class of society in his upbringing, education, and social milieu. Yet, after obtaining his degree from Cambridge University, he chose to become an economics teacher at Dhaka University, instead of choosing elite services.

Those of us who were his students in the mid-sixties still remember his simple dress, Cambridge accent, immaculate English, and his abiding commitment to the downtrodden. Those were the days when Prof. Rehman Sobhan, with Prof. Nurul Islam and Prof. Anisur Rahman, developed and propagated the two-economy theory based on the inequities of lopsided economic development between East and West Pakistan.

"Economic disparity" become a by-word of East Pakistani intellectuals and bureaucrats then, and, I venture to say, laid the rational and intellectual foundation of the Six-Points propagated by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman later.

No other movement intellectually aroused the Bengali middle class against the Pakistani elite to such an emotional height, as did economic disparity, propounded by Prof. Sobhan and his colleagues.

Prof. Sobhan taught for decades at Dhaka University and a significant corps of today's civil servants, diplomats, economists, administrators, bankers, social scientists, teachers, etc. were his direct students. It was a great experience to listen to him delivering his lectures, whether on railroad development in nineteenth century US, the slaves' transformation into wage earners after the US civil war, Japan's Meiji Restoration, the kulaks' extermination in the Russian Revolution's, or income distribution.

Those of us who came from the backwaters of Bangladesh -- the villages -- the Dhaka University department of economics offered a window of opportunity to listen to and learn from the country's brightest economists, and Prof. Sobhan figured prominently.

Like many distinguished Bangladeshis, Prof. Sobhan could have chosen to settle down in any developed country in the West, and spend his time in relative peace and prosperity. Instead, he preferred to stay and work in Bangladesh, a country with myriad problems of poverty. He has lived through the vicissitudes of Bangladesh society and has suffered the pangs and pathos with millions of fellow citizens.

Prof. Sobhan dedicated himself to address Bangladesh's economy and polity problems -- problems and issues that needed to be addressed to make a safe passage for Bangladesh to emerge into a prosperous, democratic and equitable society.

For example, his commitment to the poor and the underprivileged takes him every year to a remote village in Delduar, Tangail, to support a high school with 2,500 students, established by an area philanthropist.

Whether at a macro- or micro-level of the economy, the driving principle for Rehman Sobhan, it appeared to me, was to create a space for the poor, empower them, and bring about distributive justice to ordinary people.

Bangladesh has a long way to go to fulfil his vision for the realisation of which he dedicated his energy and talent. For the moment, let me salute my teacher and wish him a very healthy and happy life.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments