Surrealism: From French to Bangla literature

Surrealism has been a widely-used and often misused element in art and literature of the modern era. The misuse can solely be attributed to half-literacy of the users about what it is and how to apply it. Although the misconception is widespread on a global scale, a single example may confirm the low level of understanding about surrealism among our writers. In 2000, a national institution like Bangla Academy published an English version of the Lekhok Ovidhan with a noisy title 'Dictionary of Writers' (to mean directory of writers) in which the Bangla term porabastob [meaning surrealism] was ridiculously translated as 'supernatural' in delineating the rhetorical features in the works of a poet. However, the Academy stopped circulation of the book immediately after its publication, this being a 'dictionary of errors'!

However ridiculous the translation was, this evoked in me the idea of an operational definition of surrealism so our young writers in all walks of literature, including poetry, short stories, novels and drama, can use it with a full conceptualization of the meaning of the term and of the correct mode of application.

Surrealism emerged as a movement in art and literature in the 1920s and was largely drawn upon the concepts of Dadaism, a short-lived (1916-1922) preceding movement. Every human baby, irrespective of its mother tongue, initiates the process of talking with the same set of words: da...da..dad...dad, from which the name Dadaism was derived [For close proximity of a baby to its grandfather in the extended family structure in our culture, we take it for 'Dada'. Existence of grandfathers in the western nuclear families is rare, and they take this babyish delirium for 'Dad']. A group of disgusted young writers and artists, stricken by the intellectual storms during and after the First World War, initiated Dadaism as a movement, out of frustration and dislike over then existing art and literary works of the romantic era. The group led by a Romanian poet and artist Tristan Tzara, took to the babyish nonsense expressions in poetry and artwork. Although originating in Zurich, the Dadaist poets, including Tristan Tzara himself, mostly wrote in French, and the movement rapidly spread to the English-speaking world. Despite being considered a sensational move, the large majority of critics denounced these works and argued that if these incoherent delirious dictions were accepted as poems, there would remain no difference between madness and literary pursuit. This heralded an early death for Dadaism but led to the founding of surrealism that emphasizes the use of any bizarre imagery for artful but meaningful expression of reality.

French poet Andre Breton is acclaimed to be the founding father of surrealism. Poet Evan Gall of Germany became simultaneously associated with the movement since he wrote both in German and French. This new movement had the residual effects of Dadaism at its rehearsing early stage of development, and it was Evan Gall's advocacy of meaningfulness that gave surrealism a strong footing as an acceptable element in the art of rhetoric. What Evan Gall had emphasized was a clear meaning of the expression, no matter what bizarre and fantastical imageries are created from the subconscious state of mind of a poet or an artist. From then on, surrealism often began to be termed 'super realism', which implies that surrealistic imagery can be used in poetry and artwork only when these relate to the realism in spite of being bizarre and absurd.

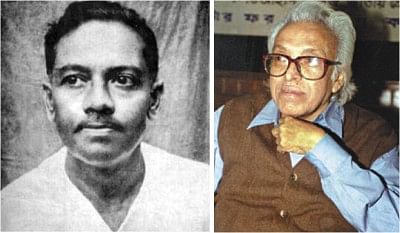

In Bangla poetry, Jibanananda Das used surrealistic imagery for the first time. He could have a good start because surrealism by then had become the bloodstream of poesy among the most talented poets in the English-speaking world, with simultaneous exercises in Spanish, Greek and other languages. We, as inhabitants of a British colony, were readily exposed to surrealism used in English poetry. Other important poets of the Thirties, including Buddhadev Bose, who wrote a lot about the movement in prose, hardly used surrealistic imagery in their poetry. In the limited scope of this small write-up, it's not my intention to present a detailed path analysis of the usage of surrealism in Bangla poetry (which I have done elsewhere in Bangla) but to help our young writers fully understand how surrealistic imagery is used to depict a realistic sequence in poetry. What I considered an operational definition in a preceding paragraph is based upon the concept of understanding an abstract ideation from appropriate examples. In a descriptive definition, it may often be difficult to differentiate even a concrete thing like a carrot from a coloured radish with the same tint of yellow-ochre! The following citations from the works of poet Jibanananda Das and Shamsur Rahman are evidence that surrealism is not just an assemblage of incoherent bizarre images and imagery but is an art element that enriches the composition of a poem with meaningful expressions:

With a slight surrealistic flavour in two imageries in the poem Porospor (Mutuality) and Pakhira (The Birds) in his first book titled Dhusor Pandulipi (Grey Manuscript), Jibanananda aptly used surrealism in Haowar Raat (Windy Night), Birhal (The Cat), Horinera (The Deer), and a few other poems in Banalata Sen; Srabonraat (Rainy Night), Niralok (Darkness), Shob (Dead Body), Ajker Ek Muhurto (A Moment Today), and Porichayok (Identifier) in Mohaprithhibi (Greater Earth); Ghorha (Horse), Sheisob Shialera (Those Jackals), and Hansh (Duck) in a later collection of poems Darkness of the Seven Stars. For my purpose, I like to quote a single imagery of Jibanananda from his Horinera that sounds:

As if there glitters the smile of Shefalika Bose,

passing through the dim light of a diamond-lamp in her hand behind a Hijal tree on the endless sylvan sky

In a dim-light environment, the charming smile of the lovely Shefalika Bose is spread across the entire horizon on the sylvan skyis apparently a bizarre imagery but is not incoherent with and detached from the central theme of the poem because metaphorically this is an extremely artful depiction of the beauty of a clear blue sky behind the canopy of a forest.

Following this kind of sporadic usage by Jibanananda Das, poet Shamsur Rahman used surrealism in his works with its various dimensions. Interestingly, his predecessor and contemporary poets of the Forties and Fifties rarely used surrealism in their works. Rahman's diction has always been an admixture of realistic and surrealistic images and imageries in his works from beginning to end. A unique feature of Rahman's poesy is a continuous and spontaneous shifting from the conscious to the subconscious state of mind and vice versa. As a result, we are exposed to surrealistic images and imagery even in poems that we consider adherent to extroversive political and social commitment, for example, Bornomala Amar Dukhini Bornomala [Alphabets My Afflicted Alphabets), Asader Shirt (Asad's Shirt), Bangladesh Swapna Dekhe (Bangladesh Does Dream). However, the poet, especially at the early phase, was mostly inclined to an introspective individualism. To exemplify how his surrealism turned into 'super realism' with direct coherence with the central theme of his poems, I would like to cite and explain two of his pieces both from introspective and extroversive categories:

a. Who is that black horse, fluttering its long fur on neck,

running across an obscure and distant field painted with fire, often shows up to take him away

b. Like a flaming piece of cloud Asad's shirt does fly on air, across the sky

The imagery in (a) is quoted from the poem Jonoiko Sohiser Chhele Bolchhe (Monologue of a Horse-Trainer's Son), included in Rahman's third book of poems Biddhwasta Nilima (The Destructed Blue) and the one in (b) from Asad's Shirt, included in the fifth book Nij Basbhumay (In My Own Land].

The black horse in the first imagery is a symbol of death that often shows up in the subconscious state of mind of a horse-trainer, now old, sick, and bed-ridden for quite a long time. The use of the pronoun 'who' for a horse is an additional element of poesy for personification. The absurd flight of a bulleted, blood-tinted shirt of a martyr across the sky in the second imagery in (b) depicts the nationwide transmission of the feelings of the cause Asad died for during the political upheaval and mass upsurge in the Sixties against the Pakistan military junta.

Both imageries are apparently absurd and represent magical fantasy, an important component of surrealism but these are very closely connected to a meaning.

The article, as I said, is not intended for a detailed path analysis of surrealism in our poetry and artwork. It is rather an attempt to make it clear that surrealism is not an assemblage of bizarre and fantastical expressions segmented from the central theme of a poem or an artwork, as frequently observed nowadays in the works of those inclined to this trait.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments